Recognizing Artist Soldiers in the Permanent Collection

Every summer, the Georgia Museum of Art participates in the National Endowment for the Arts’ Blue Star Museums program, which offers free museum admission to military families from Memorial Day to Labor Day. We created this online exhibition focusing on artists who served in the military in 2020, during our pandemic-related closure. We’re back open now, but the exhibition lives on and has been updated with some new artists. It’s organized chronologically and moves beyond the United States.

This is by no means a complete list of all the artists in our collection who served in the military. As we find more and locate or take images, we’ll expand this online exhibition. Have thoughts about ones we should add? First, search our collections database to see if we own works by them. Then let us know through this contact form.

Revolutionary War

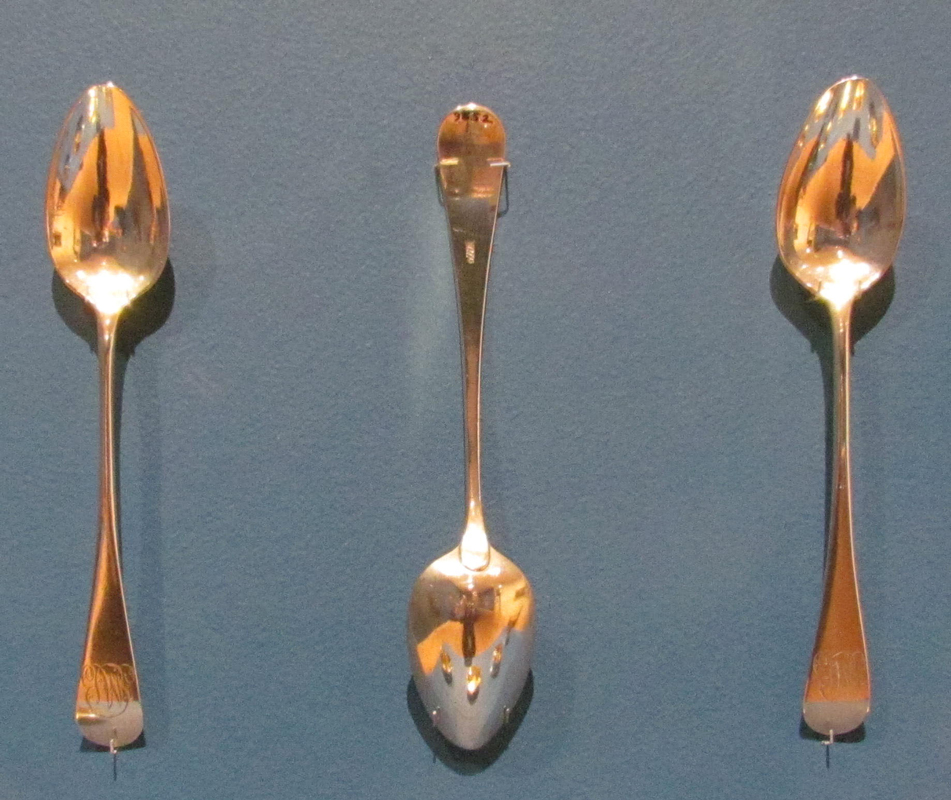

Paul Revere

American Revolutionary War patriot Paul Revere was also a silversmith. He likely made these teaspoons in between two separate periods of military service. He had already served in the provincial army during the French and Indian War, beginning in 1756. He spent time at Fort William Henry at Lake George, New York, as a second lieutenant. Following his famous midnight ride to warn Americans that the British were coming, he served as a courier and printed money with which to pay troops. He then joined the Massachusetts militia during the Revolutionary War, where he defended Boston Harbor as a lieutenant colonel in the artillery. He used his engineering skills to measure cannonballs accurately. Following the disaster of the Penobscot Expedition in 1779, he was asked to resign, but eventually exonerated in 1782.

The U.S. Civil War

James McNeill Whistler

James McNeill Whistler attended West Point (the U.S. Military Academy), where several of his relatives had gone. His father also taught drawing there. Col. Robert E. Lee was the superintendent at the time and expelled Whistler for numerous reasons, including bad grades, long hair and lack of respect for authority. Whistler later got a job as a draftsman mapping the U.S. coast for military and maritime purposes but also found this work uninspiring. He spent his time drawing mythological creatures in the margins. He moved to Paris shortly thereafter and made a name for himself as an artist.

World War I

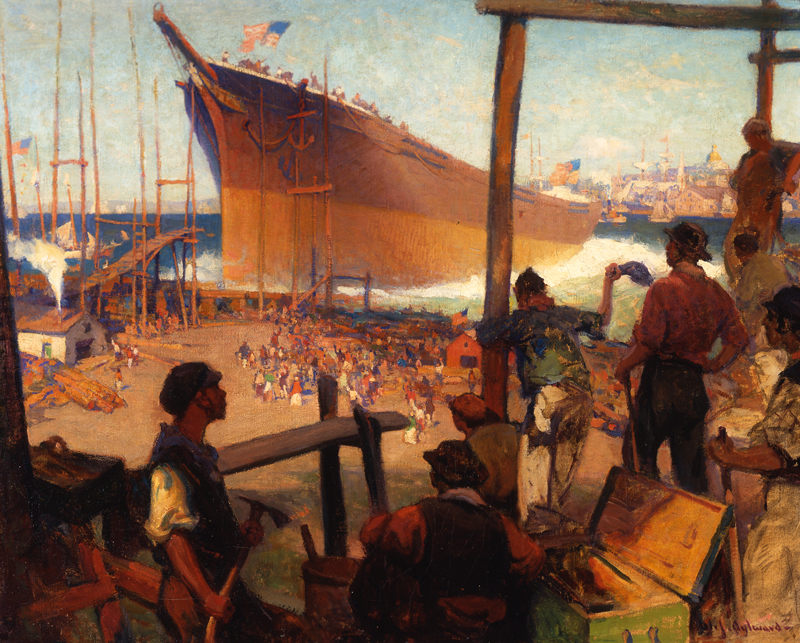

William James Aylward

Capt. Aylward was one of eight official artists with the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I. He traveled with the army and documented its fighting in France, created 26 works on a wide variety of subjects. He covered widespread casualties as well as ports and transportation systems. Following armistice, he painted at the port of Marseilles.

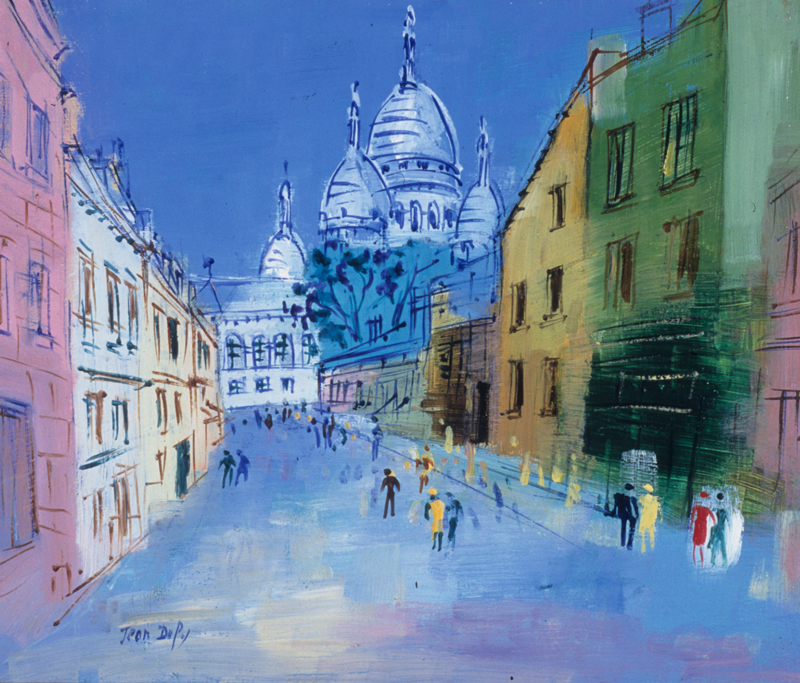

Jean Dufy

Dufy did his compulsory military service from 1910 to 1912 in a cavalry regiment. He was then drafted into the French army in 1914, during World War I, shortly after his first exhibition. He served as an ambulance driver, then trained in artillery. He painted in his quieter moments. He survived the war and recovered in Val-d’Ajol, in the Vosges region of France, before moving back to Paris. This painting shows a church on the hill of Montmartre, a bohemian district of Paris.

Albert Eugene Gallatin

A writer and art collector, Gallatin also served in World War I in the naval reserve. He turned his art knowledge to the war effort, too. As a civilian, he directed one committee that organized exhibitions of propagandistic art and another that encouraged artists to make it. He also wrote a book on the subject, “Art and the Great War,” published in 1919.

Palmer Hayden

Born Peyton Hedgeman, Palmer Hayden got both his name and his first artistic training from the U.S. Army, in which he served for almost 10 years. In 1911, he enlisted in the all-black Company A, 24th Infantry Regiment, and was deployed to the Philippines in the cartography unit. Second lieut. Arthur Boetscher gave him drawing lessons in their spare time. The story goes that a mispronunciation by a commanding officer led to his name change. When his first tour was up, he enlisted again, serving at West Point in the black detachment of the 10th Cavalry from 1914 to 1920. There, he took a correspondence drawing course, on which he spent most of his monthly income. After his army years, he worked numerous menial jobs while working on his art but eventually became well known as an artist.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Kirchner volunteered for service in the German army at the beginning of World War I, enlisting as a driver in the artillery to avoid being drafted into the infantry. The following year, he was discharged after suffering a nervous breakdown; he also became addicted to morphine. His painting “Self-Portrait as a Soldier” (1915) shows him with a missing hand. This was not accurate. Instead, it served as a representation of his mental state or his feelings about war. This drawing dates from before his military service. The Nazis later declared his work “degenerate.” Kirchner committed suicide in 1938.

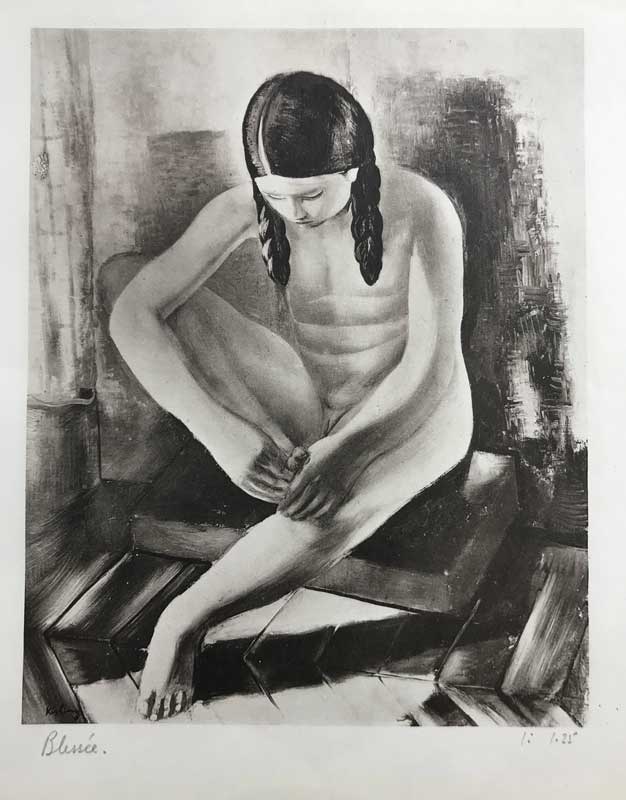

Moïse Kisling

Moïse Kisling achieved his French citizenship through military service. He was born in Austria-Hungary to Jewish parents, then moved to Paris in 1910 to pursue and study art. At the outbreak of World War I, in 1914, he volunteered for service in the French Foreign Legion and was seriously wounded in the Battle of the Somme. His service let him become a French citizen. Although he was 49, Kisling volunteered for army service again in 1940 during World War II. When the French Army surrendered to the Germans, he emigrated to the United States, fearful for his safety as a Jew. He returned to France after the war.

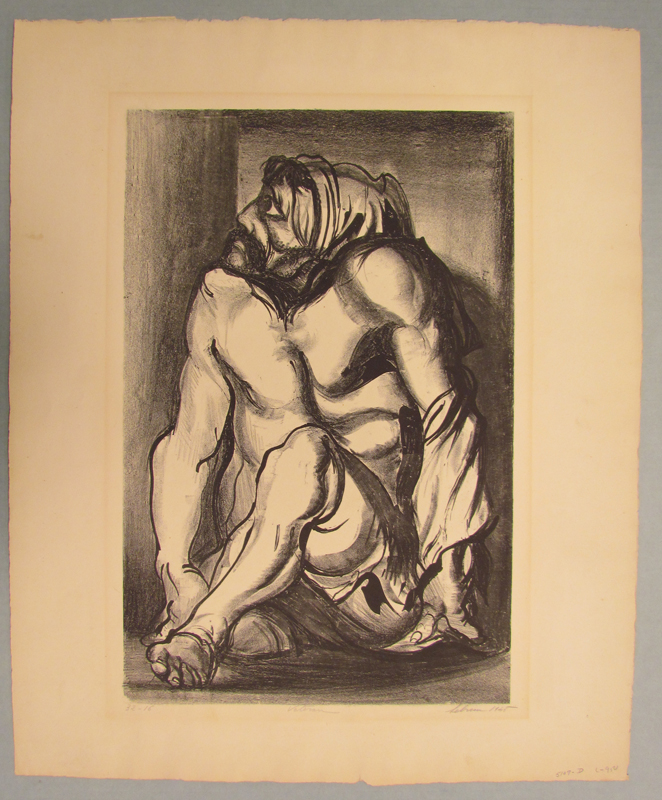

Rico Lebrun

Artist Rico Lebrun created this image, titled “Veteran,” in 1945, as part of a series of lithographs he made as World War II drew to a close. Lebrun had served in the Italian armed forces from 1917 to 1920. As a result, he was very anti-war, and he returned to the theme throughout his artistic career. The New York Times quoted him, in his obituary, as saying, “I draw and paint with one desire: to bring about the forms of a human image uniquely mine. If I have a morality guiding me it is this: that the forms used must have their own kind of splendor, their own impassioned eloquence. Without this the subject is a ruse, not a theme. The human image as I see it cannot be fabricated by conceits, but may condescend, now and then, to be measured by love. Its terrain is immense.” In other words, he was always aware of the human cost of war, something that this image communicates without words.

Fernand Léger

Born in Normandy to a cattle farmer, Fernand Léger originally trained as an architect before turning to art. He did his required military service from 1902 to 1903, in Versailles. Paul Cézanne’s works inspired him to focus on geometry, and his work became more and more abstract. When World War I broke out, he was mobilized in August 1914 for army service once again and spent two years at the front in Argonne. While there, he made many sketches of artillery, airplanes and other soldiers. In September 1916 he almost died after a mustard gas attack by the German troops at Verdun. He said that his experiences in the war made him want to move away from abstract art and “to paint in slang with all its color and mobility.”

John Singer Sargent

Although Sargent is best known for his society portraits, the British Ministry of Information commissioned him as a war artist during World War I. In that role, he traveled in France and Belgium, trying to capture the scale of the conflict. “Gassed” is perhaps his best known work of the time, showing the effects of a mustard gas attack on soldiers. You can read more about his wartime work here.

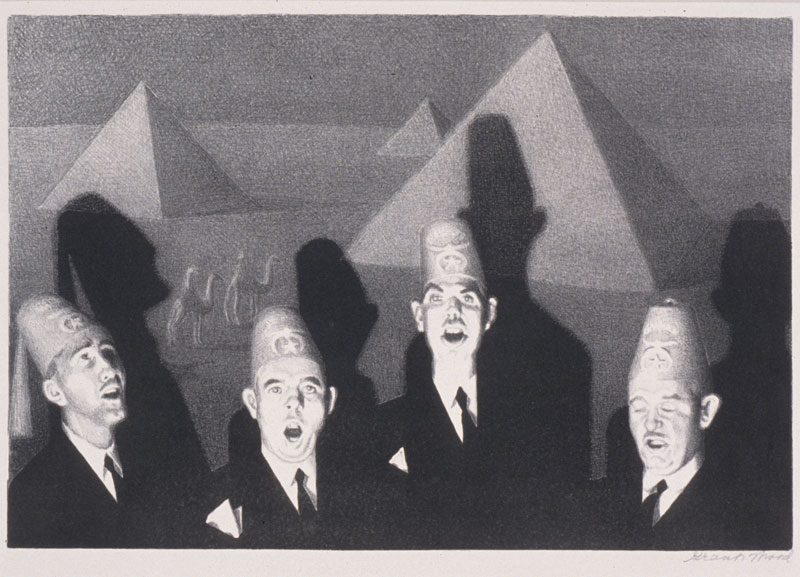

Grant Wood

Grant Wood is best known for painting “American Gothic,” but there was more to his career than that. Early in his life, toward the end of World War I, he joined the Army Corps of Engineers. He was stationed outside Des Moines, Iowa, at Fort Dodge, where he also sketched portraits of his fellow soldiers. After an appendicitis attack landed him in an army hospital, he was transferred to Washington D.C., where he joined the American Expeditionary Force Camouflage Division. Charged with camouflaging heavy artillery and creating convincing cannon “dummies,” he used what he had learned from theater design. He said, “It was a difficult job. They took airplane photographs before and after our work was finished. Grass photographs like velvet, every footstep leaves its mark. We had to dig the hole for the cannon and fix it so that not a mark showed.” The SS Grant Wood, a Liberty ship built in the United States during World War II, was named for him.

The Spanish Civil War

Pierre Daura

Pierre Daura served in the military twice, not including his work in a munitions factory during World War I, when he was too young to enlist. From 1917 to 1920, he served three years of compulsory Spanish military service on Menorca, then returned to Paris. In February 1937, he returned to his native country to fight against General Francisco Franco’s armies in the Spanish Civil War, serving as a forward artillery observer. He made many works of art that address that time, showing his fellow soldiers. He was seriously wounded on the Teruel Front in August 1937 and given a medical discharge. Because he refused to return to Spain after the war, his Spanish citizenship was revoked by the victorious Franco government.

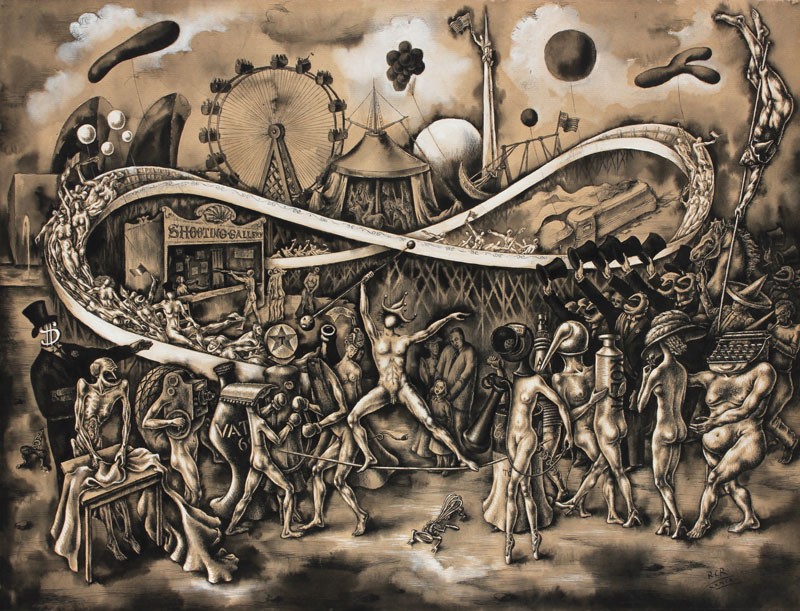

Rudolph von Ripper

Rudolph von Ripper worked in a circus and a coal mine before joining the French Foreign Legion in 1925. Living on Majorca in 1933, Ripper created a series of powerful antifascist autobiographical drawings, reflecting his universal opposition to oppression and powerful dislike for the recently empowered Nazi Party. Returning to Berlin and carrying banned literature, he was arrested in October 1933 and transferred to KZ Oranienburg, an early concentration camp used at the time as a prison for political enemies of the Nazi state. He was released after a few months, then volunteered in 1936 to fight in the Spanish Civil War against Francisco Franco and his Nazi supporters as part of the International Brigade. He emigrated to the United States and, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, tried to join the US Army but was rejected for several reasons, including his numerous wounds. He was allowed to join the Army Medical Corps, training in Texas while creating posters for the Office of War Information, leading him to a fateful appointment as a war artist with the 34th Infantry. He was soon interrogating German prisoners in North Africa, ultimately transferring to the Military Intelligence Service while maintaining his work as a war artist alongside Mitchell Siporin (see below). In January 1944, at Anzio, Italy, he killed 17 of the enemy with a sniper rifle. Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Ernie Pyle noted, “Von Ripper is so calm and so bold in battle that he has become a legend at the front.”

Ripper also took part in larger undercover operations including aiding in the liberation of Rome by helping the British A-Force as an American officer of Austrian royal lineage disguised as a German priest on a spying mission for the British. He became Captain Ripper in September 1944 when he began working directly with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency. He parachuted into Austria to link up with the resistance, facilitating the liberation of his homeland. He also worked to ensure that art by Bruegel, Titian and Rubens hidden by the Nazis was transported to the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. After the war ended, Ripper continued as an OSS officer, bringing Nazi officials and Gestapo agents hiding in Austria to justice.

World War II

Leonard Baskin

Leonard Baskin was one of the greatest printmakers and sculptors of the 20th century. His father was an orthodox rabbi. Already an established artist, Baskin served in U.S. Navy in the Pacific at the end of World War II (1943 to 1946), followed by a brief stint in the Merchant Marines. He made a Holocaust Memorial at the First Jewish Cemetery in Ann Arbor, Michigan, as well as a series of woodcuts about the Holocaust during the mid-1990s, including this one, the title of which appears in Hebrew on the print and comes from a Yiddish proverb.

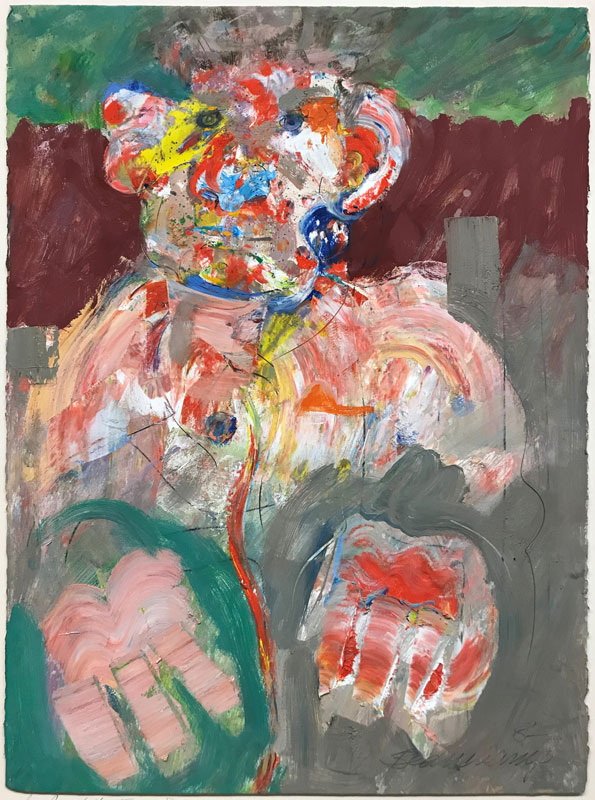

Robert Beauchamp

Robert Beauchamp was born in Denver, Colorado, and joined the U.S. Navy during World War II, after studying art for a year with Boardman Robinson at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Interviewed in 1975, he said, “As you get older you think it was a marvelous experience. But when you’re there, it’s not so marvelous. We went around the world. I was in the Armed Guard. You know what that is? In the Navy, it’s a gun crew on Merchant Marine ships. We were at sea, the longest a month, then every week we’d hit a new spot. I was in the Navy three years and I was at sea about a year and a half. The other year and a half I spent in San Francisco.” After the war, he returned to study more with Robinson, then built a career as an artist, including some time at the University of Georgia, which is when he painted this image.

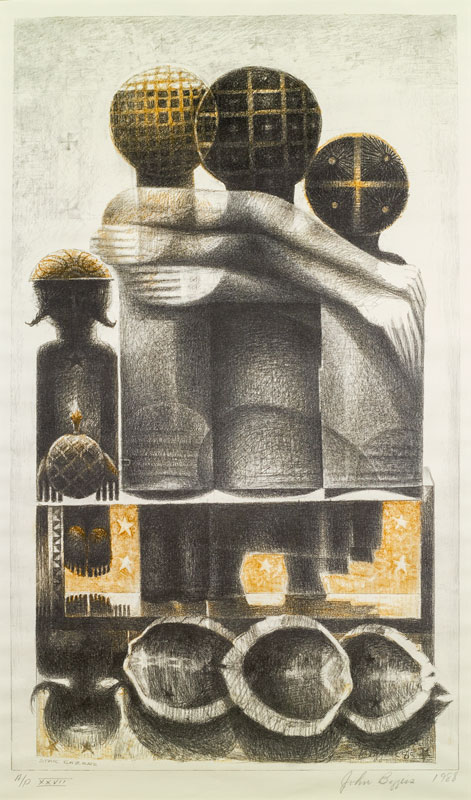

John Biggers

Best known as a printmaker, a muralist and a teacher, John Biggers founded the art department at Texas Southern University in Houston (then called Texas State University for Negroes) and taught there for 34 years. Biggers’ grandmother had been enslaved, and she told him stories about her experience that left a lasting impact. Although he had initially intended to be a plumber, he discovered art and said, “I began to see art . . . as a responsibility to reflect the spirit and style of the Negro people.” While attending Hampton Institute, he took an art class from Viktor Lowenfeld, a Jewish refugee who had fled Nazi persecution; that class made Biggers want to study art. In 1943, he was drafted into the U.S. Navy, which was still segregated. Biggers was stationed at Hampton, where he used his art skills to make models of military equipment for training purposes. He was discharged in 1945.

Marie Bleck

A high school teacher and Federal Art Project artist, Bleck entered the WAVES (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service in the US Navy) in 1943. She assigned to the intelligence service in Washington, D.C., where she worked as an aerographer in the weather section. After leaving the service in November 1945, she went to Juneau, Alaska, where she worked for the weather bureau.

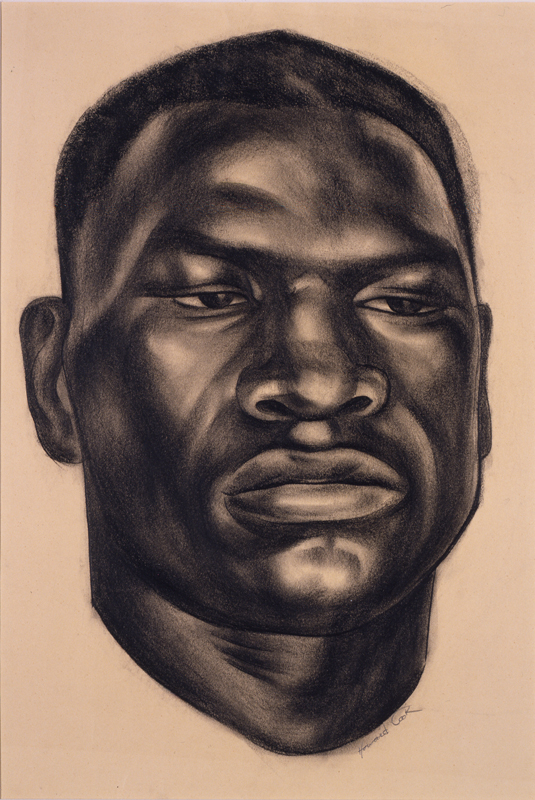

Howard Cook

Already well known as an artist for his New Deal murals, Cook led the U.S. Army’s War Art Unit as part of the 43rd Infantry Division in the South Pacific during World War II for six months. He spent his name making drawings and paintings of soldiers and was treated the same as the other military men. He wrote to his wife, the artist Barbara Latham, “We got a good taste of what it feels like to slave and sweat in the steaming stink of a jungle and can well imagine what it means to die or lie wounded in the . . . slimy mud.” His tour ended shortly after Congress voted to cut off funding for the unit.

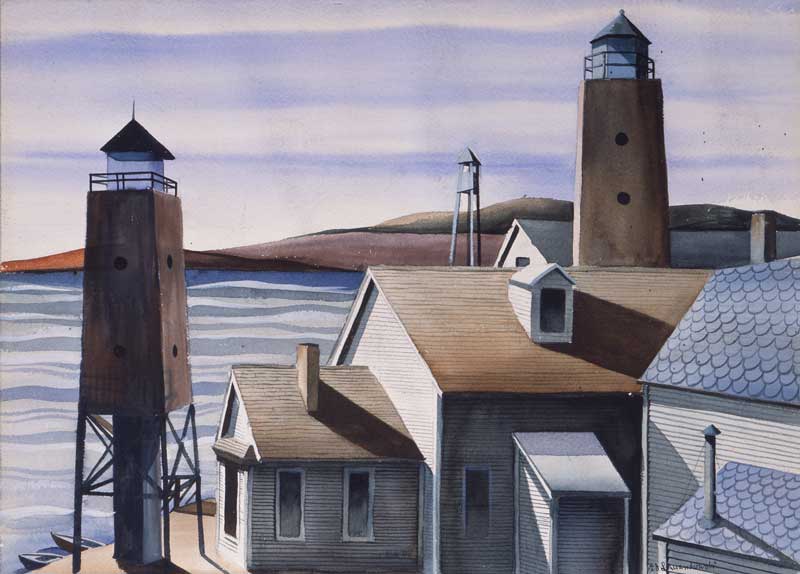

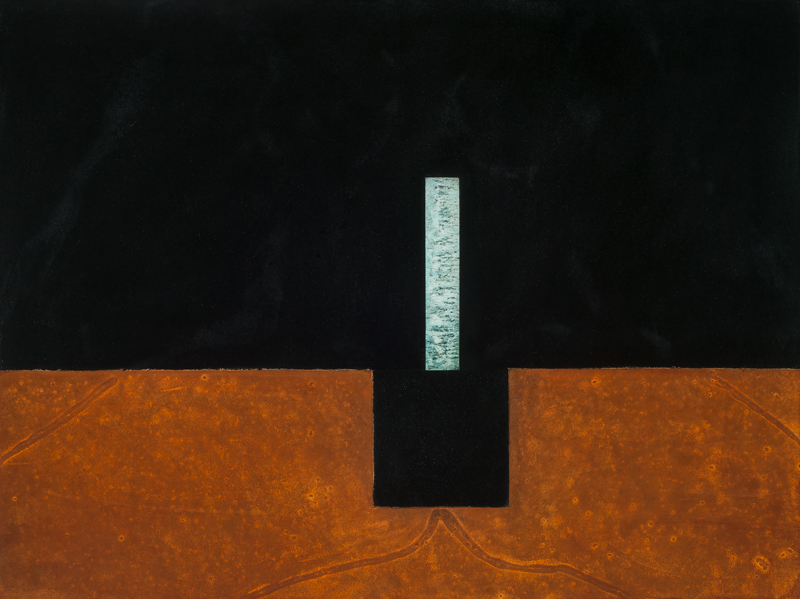

Ralston Crawford

Already an established artist, Crawford was drafted into the Army Air Forces in 1942, where he served as a master sergeant. He ended up as chief of the Visual Presentation Unit in its weather division, where he made weather maps. He would eventually show these maps at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery, and critics appreciated them. Fortune magazine took notice and assigned him to cover the detonation of two nuclear weapons on Bikini Atoll in 1946. He was the only painter present, and he rendered the tests in an abstract form in several images, including this one. Crawford received an Army Commendation ribbon for his service.

John Steuart Curry

Curry did not serve in World War I, but it conditioned his feelings about military conflict. He made anti-war art including the painting “Parade to War: Allegory” (1938). During World War II, Abbott Laboratories commissioned him and other artists to make medically themed art for the Surgeon General’s Office. Curry was assigned to Camp Barkeley, in Texas. There, he acted like a soldier, wearing a uniform and eating with the men. He sketched training battalion units as they practiced medical evacuations, obstacle courses and the like.

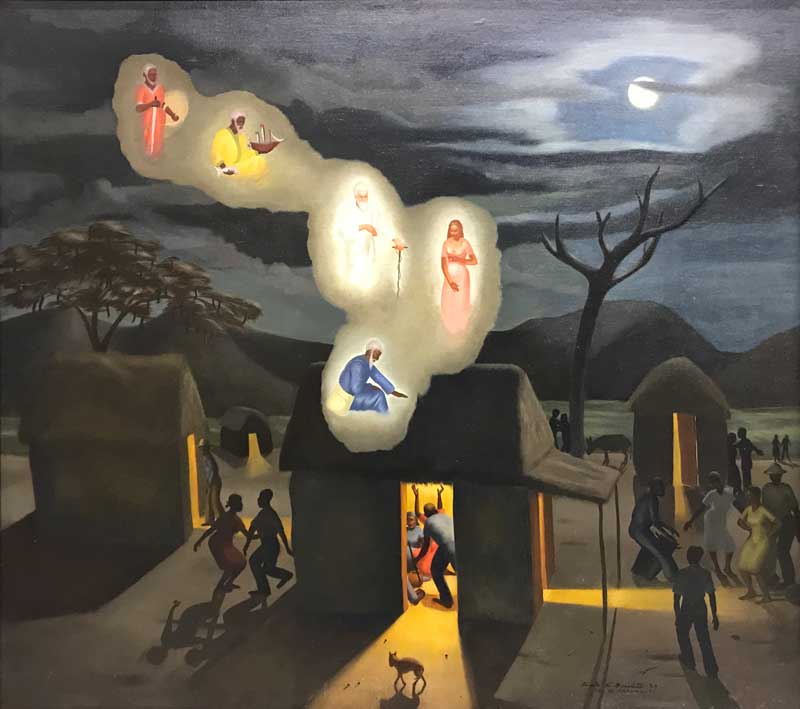

Angelo Di Benedetto

Born in Paterson, New Jersey, Angelo Di Benedetto was already an artist, with a degree from Cooper Union, when he joined the military, in 1938. As part of his military service, he toured Haiti (where he made this painting) and Africa. His Haitian paintings launched his career as an artist when Life Magazine reproduced them. He was stationed at Buckley Field in Denver from 1945 to 1946 and stayed in Colorado once he completed his service. During World War II, he served as director of camouflage, foreman of native laborers and an interpreter in Eritrea. He then received a direct commission as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Air Corps in the First Photo Mapping Squadron, leading groups as a guide and interpreter and doing ground control. His artistic skills were directly related to his military work.

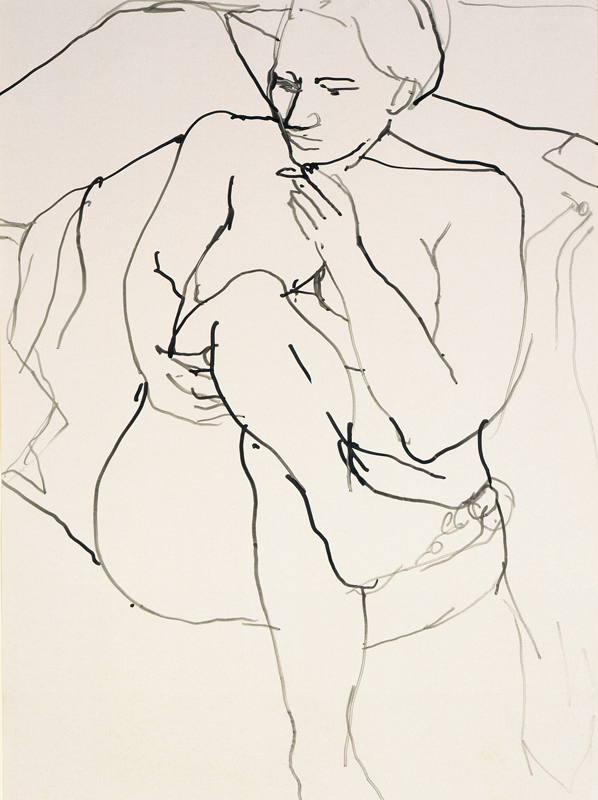

Richard Diebenkorn

Diebenkorn benefited from his service in the Marine Corps from 1943 to 1945 due to his ability to visit museums. Stationed in Quantico, Virginia, he saw art at MoMA, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Phillips Collection. He also spent time in southern California and Hawaii, where he made sketches and watercolors of soldiers. He worked in the cartography unit and received both “art materials and free time,” which let him grow and develop as an artist. He also went to the California School of Fine Arts on the GI Bill.

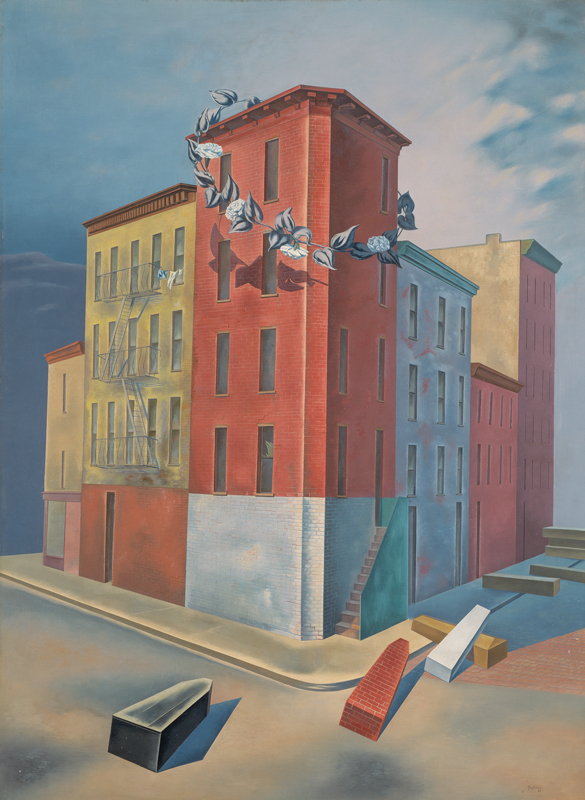

O. Louis Guglielmi

Born in Cairo, Egypt, Guglielmi moved to the U.S. with his family in 1914. He was interested in and made art from a young age and became a naturalized citizen in 1927. He worked for the Federal Art Project during the Great Depression. This work addresses the poverty that President Franklin Roosevelt tried to solve through government programs. During World War II, he served with the Army Corps of Engineers from 1943 to 1945.

Peter Hurd

The New Mexico artist Peter Hurd also studied with Andrew and N.C. Wyeth in Pennsylvania. He served as a war correspondent for Life magazine during World War II, traveling with the Air Force and making sketches of Ascension Island, Europe, India, Africa and British Guyana. He traveled to most continents involved in the war. Rather than photographing his scenes and subjects and creating his images later, he worked on site, giving his war work an immediacy that comes through in the images. The painting above dates from before the war and uses some egg tempera, his preferred medium in those years. Hurd’s years with the Air Force let him master the use of watercolor and loosened up his work due to the speed that was required by those war sketches.

Angelo Ippolito

Born in Italy, Angelo Ippolito served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1945 during World War II, where he was stationed in the Philippines. Like many artists, he was able to use funds from the GI Bill to attend art school when he returned from duty.

Jack Kehoe

John Daniel Kehoe, known as “Jack,” joined the Merchant Marines during World War II, then taught art on military bases. After the war, he studied art many places, including in Rome. Kehoe taught at UGA’s Lamar Dodd School of Art for more than 30 years, during which time he founded the UGA Cortona Study Abroad program. He served as its director for more than 20 years, and the campus there is named in his honor.

Jacob Lawrence

Already known as an artist, Lawrence was drafted into the U.S. Coast Guard during World War II. At first, he served in a segregated regiment, but in 1944 he joined the first racially integrated crew on the cutter Sea Cloud. He worked as an artist to document military life as he traveled to Europe with the crew. Lawrence made nearly 50 paintings during his service, but all were lost. You can see black-and-white images of some of them here. He made this painting after the war, and it shows his signature use of primary colors and flattened form.

Edmund Lewandowski

Like many other artists during World War II, Edmund Lewandowski made maps and camouflage. In his case, he did so from 1942 to 1946 for the U.S. Army Air Forces and U.S. Air Force. He also made a major mosaic mural for the exterior of the War Memorial Center on the campus of the Milwaukee Art Museum. This mosaic uses more than 1 million pieces of glass and marble and pictures slightly abstracted Roman numerals in purple, blue and black. The numbers are the beginning and ending dates of the U.S. involvement in World War II (MCMXLI [1941] through MCMXLV [1945]) and the Korean War (MCML [1950] through MCMLIII [1953]). At the time, it was the largest outdoor mosaic in the U.S. Lewandowski also made mosaic tiles for the 20th anniversary of the building, in 1977, that symbolize the signs for the five branches of the armed forces: Army, Navy, Marines, Air Force and Coast Guard.

Norman Lewis

Lewis’ military experiences led him to a dramatic change in style. Before World War II, he had focused on social‑realist art, working for the Works Progress Administration. His military service during the war made him realize the hypocrisy of the U.S. fight “against an enemy whose master race ideology was echoed at home by the fact of a segregated armed forces.” Returning home, he no longer believed in the power of representational art to effect change and turned to abstraction, as with this early abstract work from the year the war ended.

Gabor Peterdi

Gabor Peterdi was born near Budapest and emigrated to the US in the late 1930s. Upon receiving US citizenship in 1944, he promptly volunteered for military service. Serving in the army’s Anti-Tank Infantry in the 100th Division in Southern Germany, his group of soldiers was strafed by German fighters in early 1945. He was then transferred to G-2 6th Corps, acting as a cartographer, and eventually assigned to Austria, where he located, captured and enabled the return of Hungarian war criminals. After his release from active duty, he returned to New York. Many of his prints focused on the horror of war, using religious imagery. This print appears to show a rooster-like figure, a symbol for Peterdi of male aggression.

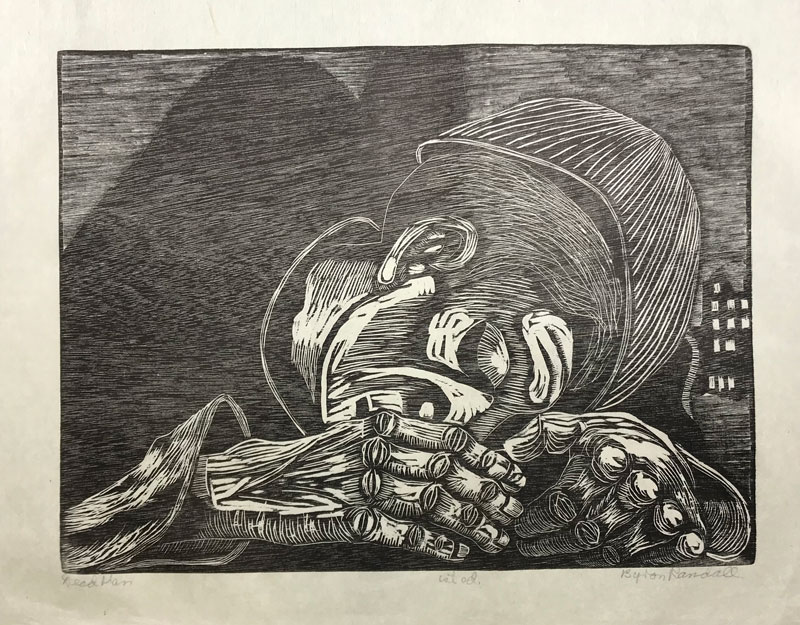

Byron Randall

Born in Tacoma, Washington, Byron Randall grew up in Salem, Oregon, where he worked as a waiter, harvest hand, boxer and cook for the Marion County jail to finance his art career. He cared deeply about social and trade union activism. During World War II, he served in the Merchant Marine, a combination of U.S. civilian mariners and U.S. civilian and federally owned merchant vessels. In war times, the Merchant Marine can be an auxiliary to the U.S. Navy, and can be called upon to deliver military personnel and materiel for the military. Randall made numerous works of art during his service picturing the sea and sailors. In the 1960s, he focused on what he saw as the grotesque pageantry of U.S. militarism, using a visual vocabulary that drew on the folk traditions of Mexican graphic art.

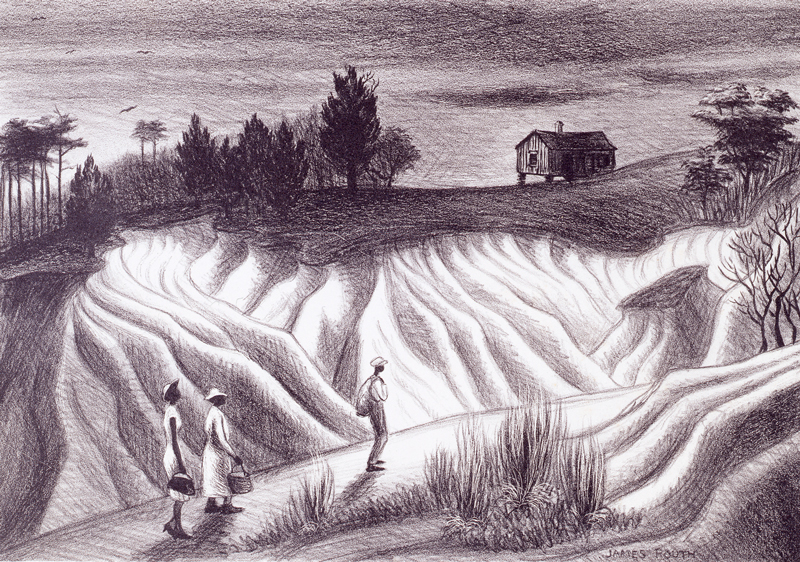

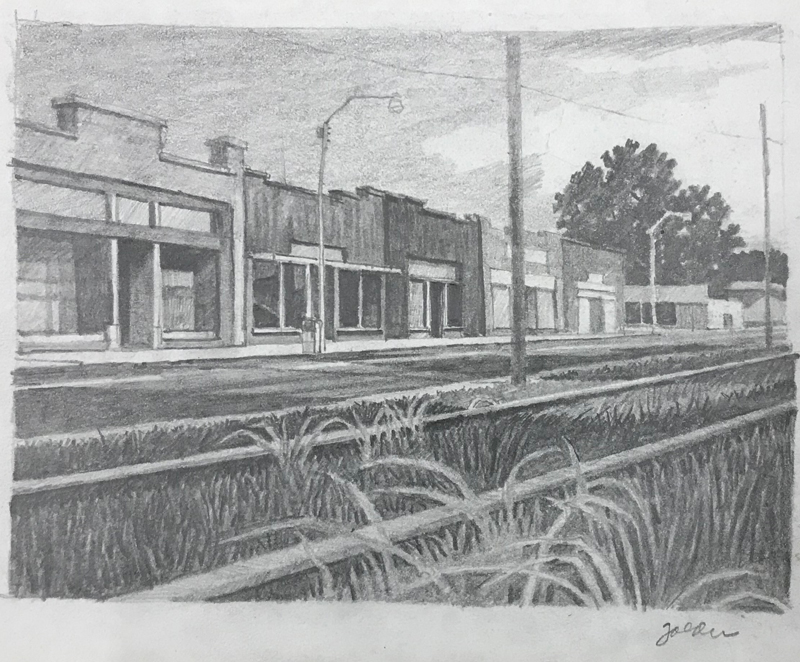

James E. Routh

The subject of a retrospective exhibition organized by the Georgia Museum of Art in 2009, Jim Routh studied at the Art Students League for four years. He received a grant from the Julius Rosenwald Fund to travel the South and make art in the early 1940s. This image dates from that trip, on which he captured many rural scenes that no longer exist. Routh enlisted in the U.S. Army after Pearl Harbor and served until 1945, including fighting on Omaha Beach during D-Day. After that experience, he went into advertising. He said, “WWII changed things for me. I made a few prints in the year or two after . . . [but] had no more contact with teachers and friends of [the] pre-war years.”

Ben Shahn

Already known as a skilled propagandist from his Works Progress Administration works, Shahn was hired by the Office of War Information during World War II to make posters. His Leftist politics meant that his posters were less patriotic than the office desired, however, and only two of them were published. Irritated by his work being called “not appealing enough,” Shahn resigned the OWI. He also made paintings that addressed the horrors of the war as early as 1944. This work addresses the need for pre-natal care and also dates from 1944.

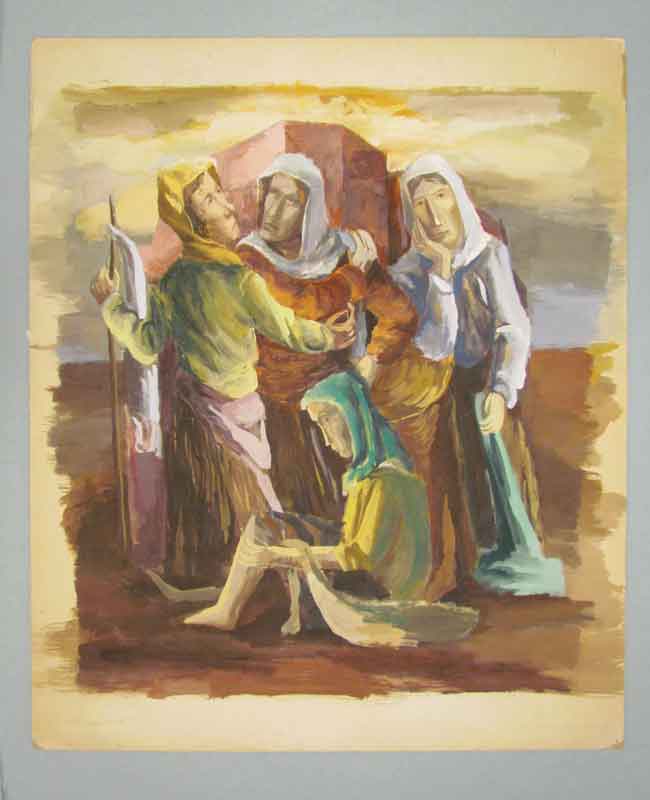

Mitchell Siporin

Born in New York to Polish immigrants, Mitchell Siporin grew up in Chicago and is best known for focusing on social concerns through his art, including a series of images related to the Chicago Haymarket Riot of 1886. He also made works addressing war profiteering in the 1930s and worked for the Works Progress Administration. During World War II, he served in the army as a war artist, where he accompanied frontline troops in North Africa and Italy, creating images that focused on the struggles of soldiers as individuals and on refugees. Although the image here dates from before his service, it bears strong similarities to the watercolors he created and sent home from abroad. Siporin served from 1942 to 1945.

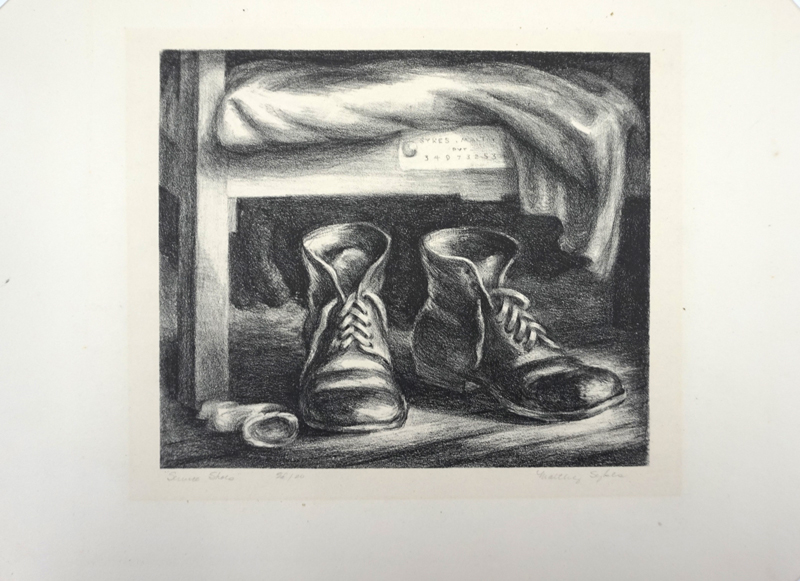

Maltby Sykes

Sykes grew up in Alabama but traveled widely, training with Diego Rivera in Mexico. He taught at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) and was drafted into the Air Force in 1943. There, he worked as a military artist in the Pacific Theatre. He also made lithographs that showed his basic training. “Service Shoes” dates from the same year as his lithograph “Flying Time” and shows a close-up of military-issued boots.

Morton Traylor

Traylor was born in Petersburg, Virginia, and grew up in Los Angeles. He came from a working-class background. His father was an electrician, and Traylor worked as a grocery clerk, a gas attendant and a highway worker. There is no evidence of his pursuing art until he was 19. He served in World War II as an aviation radio operator, then studied at the École de Beaux Arts in Paris on the G.I. Bill. He followed that up by attending Chouinard Art Institute and Jepson Art Institute in Los Angeles, where he served as the personal assistant to Rico Lebrun. Traylor went on to work for Northrop Aviation as an artist during the 1950s as well as for the New Yorker as an illustrator.

Korean War

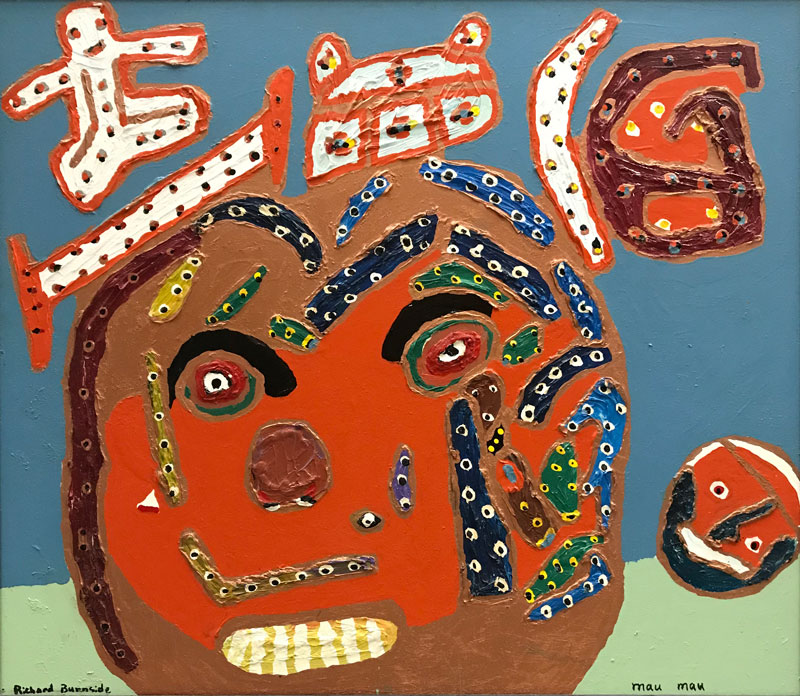

Richard Burnside

Richard Burnside served in the army as a young man, in the Korean War, where he was a cook, but a foot injury ended his career. Later, he became a chef. He said his food was so good that it would “make your stomach hurt with wanting.” He began painting to deal with the pain of that old injury and quickly found a following in Pendleton, South Carolina, where he lived. He created his own mythology and painted images from it repeatedly, especially kings and queens.

Horace Farlowe

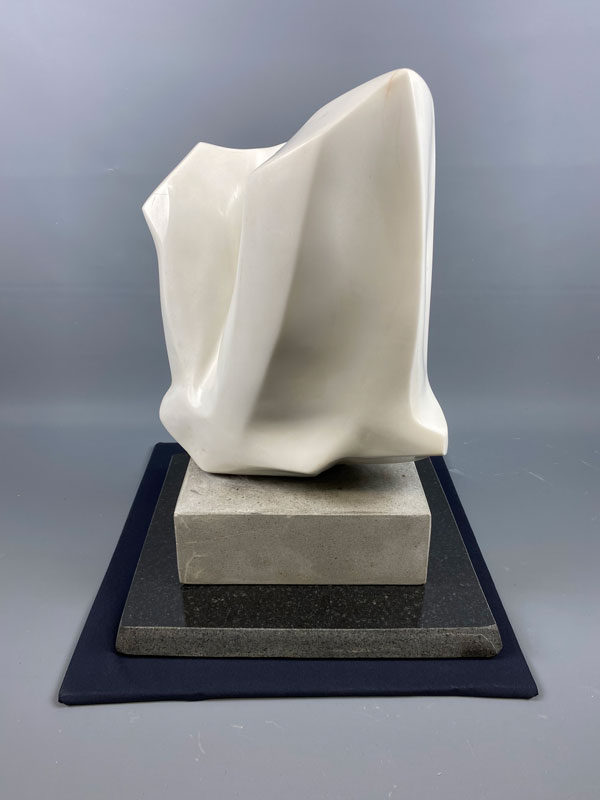

Born in Robbins, North Carolina, Horace Farlowe joined the U.S. Marines as a young man and was deployed to Korea, where he served from 1953 to 1957. When he returned to the U.S., he decided to study architecture at North Carolina State University School of Design. There he was inspired by the sculptor Roy Gussow, who encouraged his artistic leanings and gave him material to carve. He served as a visiting artist at the University of Georgia in 1979 and accepted a full-time position there in 1980, staying for the next two decades.

Rolland Golden

Born in New Orleans, Golden was a sickly child, but his health improved and he left college after only one semester to join the U.S. Navy. He was then drafted to serve in the Korean War and spent four years in the service, mostly working in teletype. The GI Bill then paid for him to attend the John McCrady School of Art, in New Orleans. Golden said that his military service gave him “the toughness I needed to pursue art – to take setbacks without quitting. It was immensely important in my evolution as an artist, husband and father, and I can now say that being in the navy changed me from a boy to a man.”

Wadsworth Jarrell

Wadsworth Jarrell was born in Albany, Georgia, and grew up in Oconee County, next door to Athens. He enlisted in the army after graduating from high school and ended up deployed to Korea. The army fostered his artistic sensibilities. While he was training at Camp Polk, in Louisiana, he was named company artist, meaning he made signs, maps and charts, and his fellow soldiers frequently asked him to paint for them, too. While in Korea, he concentrated on his duties with the battery unit, but he focused his mind on future art training and enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago once he was discharged. He was a founding member of AFRI-COBRA and allied himself with other Black artists to create work that was revolutionary in form and content.

Other Service

Sam Gilliam

Sam Gilliam grew up in Kentucky and graduated with a bachelor of fine arts degree from the University of Louisville in in 1955. He served in the U.S. Army from 1956 to 1958. Gilliam said, “I was in the ROTC, and I did basic training in Texas. We were stationed with Airborne troops and drilled by Airborne sergeants. After that I was quite lucky to be stationed in Japan. Japan was just marvelous. There were galleries and art stores, and a woodcut studio near the base. There was one person in our unit who did nothing but go to Kabuki theater. From what I had seen of the art world, I wasn’t sure if I still wanted to be an artist, but I knew I didn’t want to be a soldier. So, I grew up. I went back to school to do my thesis.” Although his work is primarily abstract, he did incorporate his army boots into a multimedia work titled “Composed.” He also received the Medal of Art from the U.S. State Department for his longtime contributions to Art in Embassies and cultural diplomacy in 2015.

Harold Rittenberry

Harold Rittenberry, a native Athenian, joined the U.S. Army at 17. To do so, he forged his parents’ signatures, then headed to Atlanta to be inducted into the Army and then to Fort Jackson in South Carolina to receive basic training. By the time Rittenberry joined the Army, the Korean Conflict had ended, and U.S forces were no longer involved in active combat operations. Even so, the “Cold War” with the Soviet Union had led to the stationing of thousands of GIs in NATO nations that bordered Soviet satellite states. In the early autumn of 1956, after receiving additional training at Fort Hood in Texas, Fort Dix in New Jersey and Fort Knox in Kentucky, Rittenberry received orders to deploy to a sprawling American military base in Baumholder, West Germany. There, he was assigned to an artillery unit charged with operating motorized vehicles used to haul cannons, radar dishes and other large equipment.

Rittenberry served in the army for three years. He found great satisfaction in learning how to operate complex machinery, including in challenging mountain conditions and sub-zero winter weather. His job responsibilities also required him to service military vehicles, thus engaging him in working with his hands in much the same way he would use them in later years when his interests turned to fabricating steel sculptures. He also made art during his time in Baumholder, and a depiction of a German castle, done in pencil on cardboard, found its way into the hands of the motor-pool sergeant. When the officer discovered who had made the sketch, he took Rittenberry aside to ask if he could keep it. Rittenberry dutifully agreed. He produced only pencil drawings during his service, and he worked in that medium only from time to time. Even so, because his sketches were so well-received by others, he began — however haltingly — to think of himself as an artist.

William J. Thompson

William J. Thompson is best known in Athens for creating the “Spirit of Athens” sculpture downtown in conjunction with the 1996 Olympic Games. He also made a memorial at Andersonville National Park, commissioned by the Georgia Natural Resources Commission to commemorate lost prisoners of all American wars. Born in Denver, Colorado, he taught at UGA’s art school from 1964 to 1983, where the sculpture studio is named in his honor. Thompson had originally intended to be a Catholic priest, and his strong faith showed up throughout his artistic career. He studied art at the Rhode Island School of Design, with an interruption in his studies to serve in the Army from 1946 to 1947.

Jack H. White

Hailing from Brooklyn, White had a long and impressive career as a sculptor, a painter and a photographer. His father was a contractor and his mother a homemaker, and White was interested in art from a very early age, taking classes at the School of Visual Arts and elsewhere. He joined the U.S. army in 1959 as a way to travel to Europe and visit art museums. He did basic training at Fort Jaffey, Arkansas, but recruiters promised him that he could be stationed in Europe if he joined the 28th Infantry, which was in New Ulm, in Bavaria, Germany. He was transferred to Augsburg and then to Munich and trained as a cannoneer (a person who fires cannons). He also qualified for the U.S. Army Rifle Team. White never saw active combat because he served from 1959 to 1962. He made many friends but also experienced significant racism and prejudice. After his service, he moved to Ibiza, Spain, where he befriended the artist Bob Thompson. He returned to the U.S. after a mental collapse but recovered and spent many years making art inspired by physics and cosmology, like this painting.