When we look at a portrait, what can we learn about the person pictured, and the artist who created it? This pop-up exhibition explores these ideas through a closer look at 19 portraits from the Georgia Museum of Art’s collection. In some, we know the identity of the sitter, whether it is a self-portrait or a portrait of another person. Others feature unknown individuals. All of the works invite us to consider questions of identity, personhood, and the relationship between artist and subject.

The exhibition was developed by students in Dr. Callan Steinmann’s FCID 5010/7010 (Introduction to Museum Studies) class while meeting at the museum over the course of the fall semester. Students selected portraits from the collection that resonated with them, and worked in groups to research the portraits, write interpretive object labels, and organize the works into thematic groupings.

Students included Britt Bennett, Karlie Byrd, Noel Corbin, Cullen Doyle, Auguste Grillo, Lucie Heidari, Brynn Hungerford, Monica Kincaide, Ivy Kolkana, Joe Leggo, Sydney Meeler, Jaylie Mergele, Emaline Newbury, Chelsea Persad, Clay Pirrone, Samaya Porter, William Sealy, Natalie Soper and Maristella Tuazon.

Self-Portraits

A self-portrait is an artist’s way of depicting themselves, allowing them to express not only their physical appearance but also their personality and identity through their art. This section shows a variety of self-portraits, representing a range of artistic styles across time.

Lewis Morley’s photographs may not be the most traditional self-portraits, yet they offer an interesting glimpse into his view of himself. Lamar Dodd shows himself with a look of introspection against an abstract background, showing techniques learned from European Modernism artists. Lucy May Stanton is known for her miniature portraits, but no matter the size, her works serve as reflections of people in the early 20th century. Käthe Kollwitz created over 100 self-portraits, often depicting herself in a rather somber mood.

As you look at these self-portraits, consider how the artists chose to show themselves. Is it traditional or more abstract? Would you have guessed it was a self-portrait at first glance? How do you view yourself?

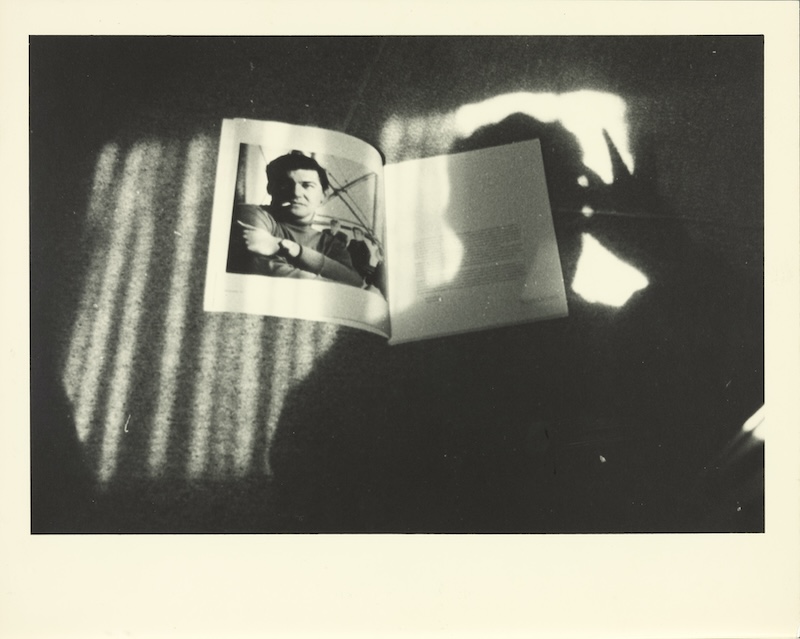

Lewis Morley was a popular British photographer of the 1960s. At first glance, one might think Morley is the woman pictured here. Instead, his self-portrait is found, out of focus, in the small mirror she holds. While her details are clear, from her haircut to her makeup, Morley makes himself barely recognizable, giving the viewer only a small, vague look at his face. Confronting traditional ideas of self-portraits, Morley forces the viewer to think of all the subtle ways the self can be shown. Would you consider this a self-portrait?

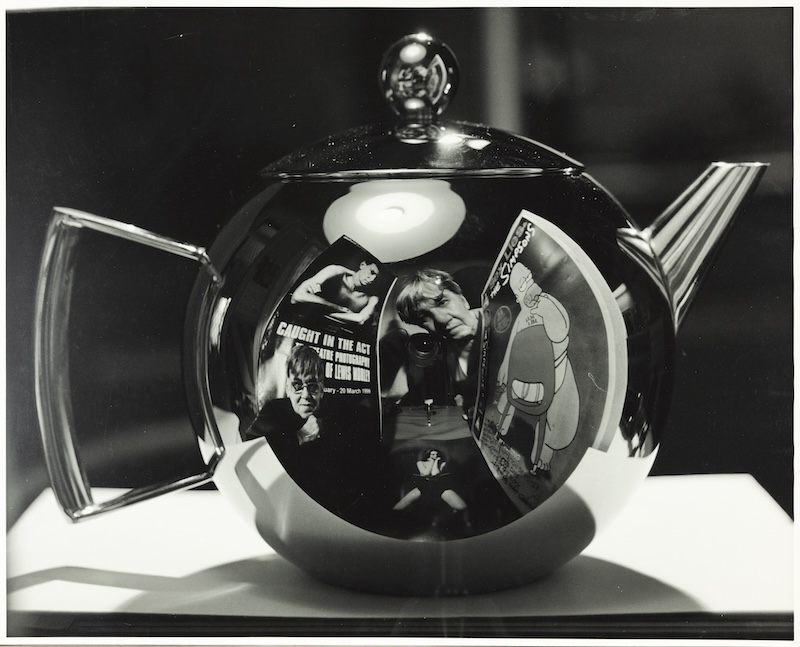

Lewis Morley plays with how he takes photographs to capture an almost mythical image. At first glance, the subject of this photograph seems to be the teapot. But look within it, and you can see Morley peering around a frame created by magazine covers and posters. This photograph shows Morley in movement, looking down to inspect the teapot. The teapot seems to be taking the dream-like image. Morley spent a lot of time studying surrealism, an art movement focused on subconscious thoughts and dreams.

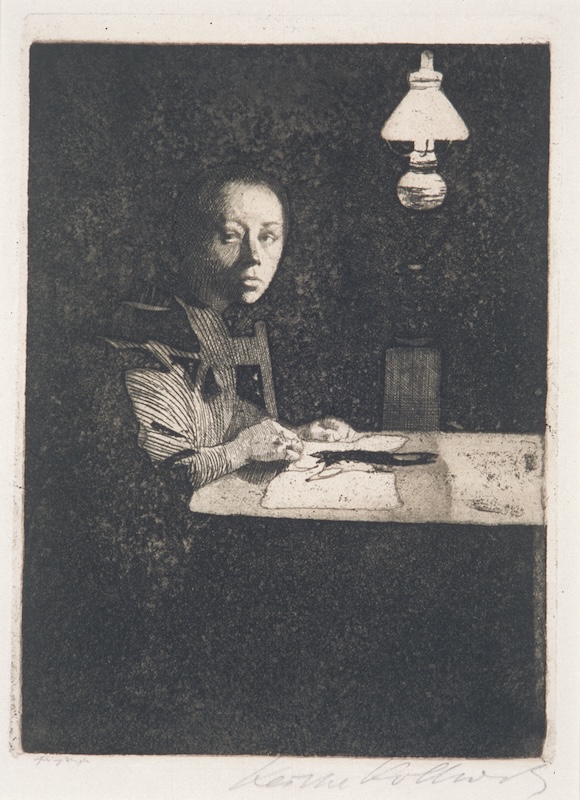

Kathe Kollwitz grew up in a progressive household, and she often showed the poor, the sick, and victims of war to give a voice to the voiceless in her art. Kollwitz became the first woman professor at the Prussian Academy of Arts, but the Nazis forced her to resign in 1933. She continued to make art and display it in secret even though the Nazi secret police threatened to send her to a concentration camp. She said, “The self-portrait is frequently revisited as an opportunity to interrogate and examine one’s own person.” What do you think her self-portrait says about her?

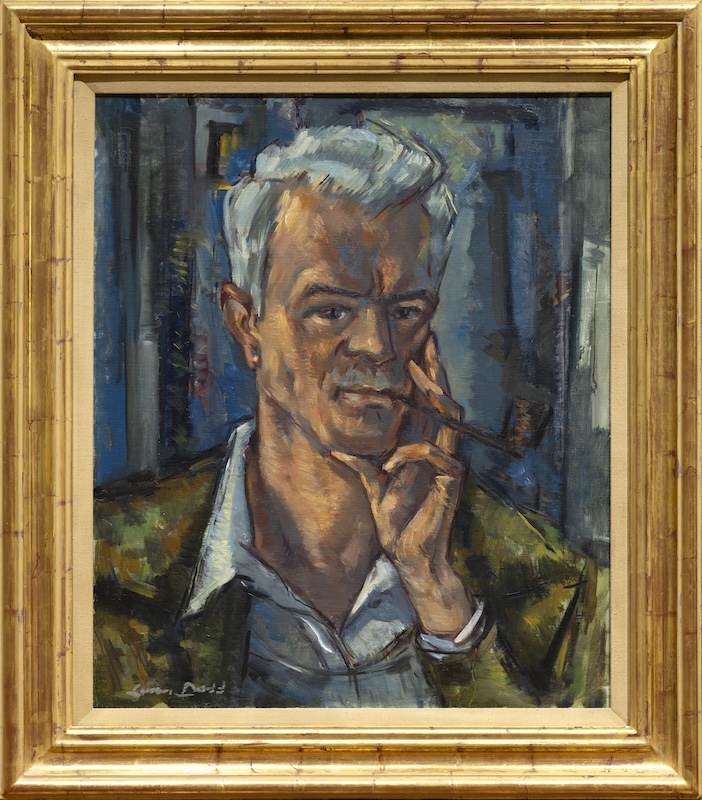

In this self-portrait, Lamar Dodd presents himself with a thoughtful expression, pipe in mouth. The geometric structure and the interplay of light and shadow show Dodd’s engagement with both realism and cubism. Dodd traveled through Europe in the 1950s, where he saw art by pioneers like Paul Cézanne. This experience shaped Dodd’s visual style, allowing him to balance emotional expression with structural order. Here, he shows himself reflecting while hinting in his techniques at the construction of modernist form, merging his identity with global artistic dialogue.

Self-portraits often show a person’s head and shoulders, but Lucy May Stanton chose to paint a full-length (head to toe) portrait of herself. Stanton was known as a pioneer of miniature portraits, not full-lengths, using watercolor on ivory. She also painted several portraits of several Georgia majors before settling in Athens, Georgia, in 1926. In “Self-Portrait, Reading,” Stanton portrays herself in an intimate setting. With her thick brushstrokes and casual pose, with one leg crossed over the other and her eyes on her book, she seems to be in her own world. As a woman working in the South during the early 20th century, Stanton’s portrait reflects the changes in women’s fashion, activism, and roles in public life.

Known Sitters

Portraits of known sitters offer rare opportunities for the viewer to engage directly with the individuals they depict. Each portrait is an interaction between the artist’s style, the subject’s physical appearance, and the relationship between the two people. This interplay of body and mind results in the final rendition of the sitter, providing a glimpse into the lives of the both the artist and the subject. Whether the artist and sitter shared admiration, a friendship, or professional ties, these dynamics are always found in the final image.

Some of these portraits are an artist’s tribute to culturally influential figures by referencing the subject’s work in the visual or performing arts. Several of these artists had a close, personal relationship with their sitters, while others admired them from afar. Consider each portrait and the information provided. What does each work tell you about how the artist may have felt about the subject of their portrait?

Portraiture often reveals the artist’s own psyche. Denon was primarily a diplomat, archaeologist, and writer, not an artist. However, he had a profound interest in the human condition. Here, he depicts Emma Hamilton, an actress and dancer, as Hecate, the Greek goddess of magic and witchcraft. Famous for her expressive “attitudes,” Hamilton modeled for many artworks that blended performance and myth. Denon captures both her charisma and the neoclassical passion for antiquity. In this work, the union of the mythic subject and the real performer emphasizes Denon’s artistic curiosity and his drive to explore identity, beauty, and the dialogue between art and the human spirit.

In 1873, Jacques Reich immigrated to the US to expand his skill in portrait etching. He eventually opened a studio in New York. Reich made etchings on copper plates of important people: American and European artists, writers, wealthy businessmen, politicians, and historical figures. Here, he captures President Lincoln in great detail, highlighting Lincoln’s distinctive facial features, including his wandering left eye. This work demonstrates Reich’s ability to blend realism with presentation. This offers viewers a sense of the historical stature and personal character of the sitter.

Carl Christian, a Black artist and longtime Atlanta public school educator, is known for his abstract works inspired by the improvisational rhythm of jazz and his optimistic outlook on life. In this portrait of jazz legend and civil rights activist Nina Simone, Christian combines textured paint with a unique canvas: window blinds. The blinds seem to block out the sun, suggesting a pause before its light breaks through, a metaphor for hope. The work’s title references Simone’s soulful cover of the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” a song of optimism amid the turmoil of the 1960s and 70s. Simone believed that every artist’s work should reflect the times they live in. Her searing protest anthem “Mississippi Goddam” captured her frustration with racial inequality, while “Here Comes the Sun” offers a message of hope. Christian’s portrait honors that balance between struggle and resilience, light and shadow.

Listen to Nina Simone’s version of “Here Comes the Sun” here.

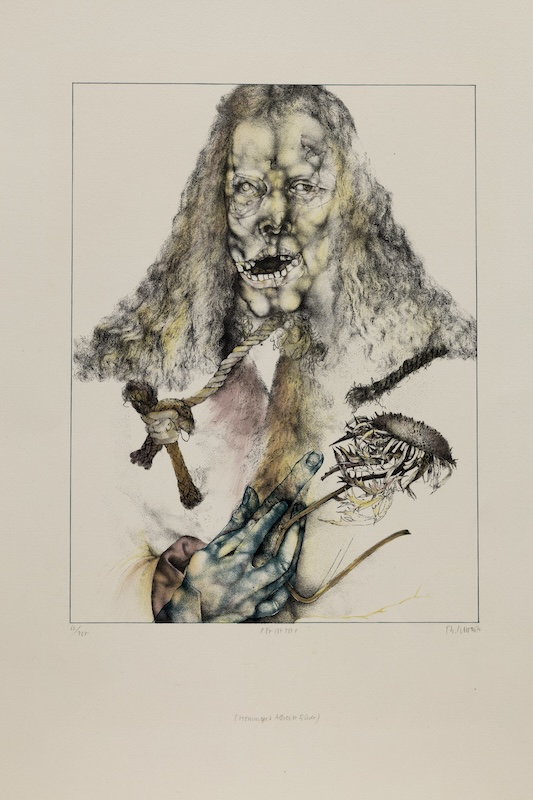

In this work, Schwarz pays tribute to the German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer while questioning what his legacy means in the modern world. The work serves as a portrait of one artist looking at another to understand himself and his time. Rather than simply copying Dürer, Schwarz reimagines him in a darker, more expressive style. By choosing Dürer as his subject, Schwarz creates a portrait of one artist looking at another to understand himself and his time.

The title is both a statement of fact and a challenge. It not only acknowledges Dürer’s death, but also hints at the loss of the ideals he stood for: faith in reason, order, and the power of art to reflect truth.

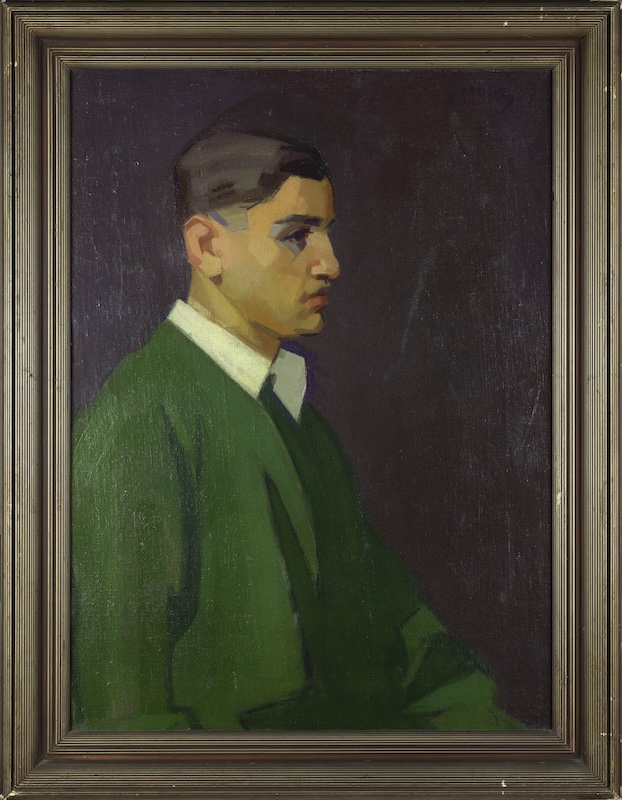

German-born artist and educator Carl Holty drew inspiration from his travels across Europe but spent most of his life in Wisconsin. Samuel Himmelfarb and Holty were both Wisconsin natives and artists who could have easily collaborated on projects beyond this portrait. Here, Holty constructs the form with broad, planar strokes, especially noticeable in the green coat and cheekbone. Edges are simplified; transitions between colors are sharp rather than blended, giving the portrait clarity. Holty uses a limited yet impactful palette, dominated by cool greens and deep purples. The sitter’s green jacket becomes the focal point of color. Vibrant yet matte, it contrasts with the warm flesh tones of the face and the neutral violet-brown background. There is a clear somberness and calmness in Samuel’s facial expression that resonates with the viewer.

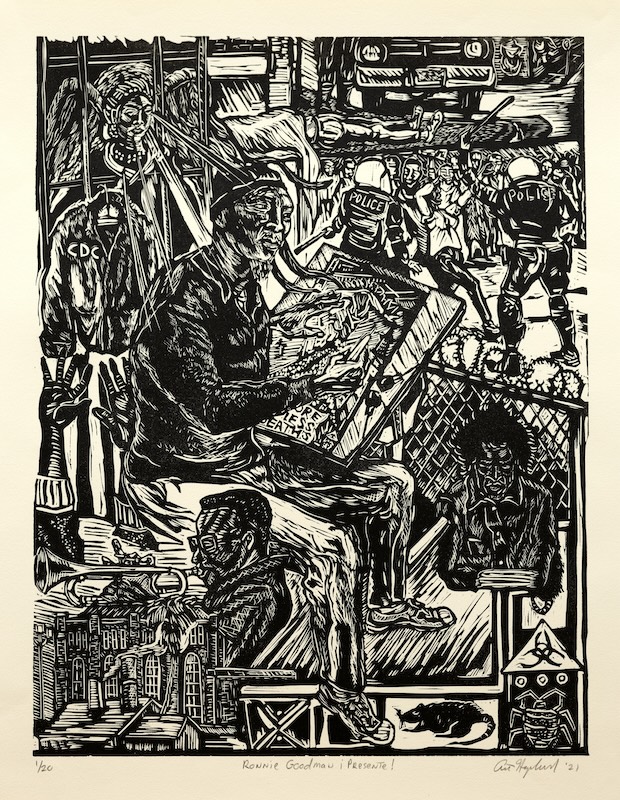

During his sentence at San Quentin State Prison, Ronnie Goodman met Art Hazelwood who taught the Art in Corrections program. After release, Goodman remained homeless but continued to create art about prison, poverty, and homelessness. Hazelwood says Goodman’s art “represented the difficult life he and his community lived, but within all his work there was a note of hope, and a sense of the power of art.” Following Goodman’s death, Hazelwood created this portrait that shows Goodman working on his linocut “No More Homeless Deaths.” Surrounding imagery references more of Goodman’s artwork, like “San Quentin Jazz.”

Inspired by the work of Renaissance painters, Brockhurst became a sought-after portraitist who painted lifelike sitters against scenic landscapes, creating surrealist compositions.

While the world was at war for a second time and America was experiencing an economic revitalization, Brockhurst created this portrait of Jeanne Laib in front of a grey sky and blue rolling hills in the distance. Her updo hairstyle, red lipstick, and matching red fingernails reflect popular women’s styles of the 1940s. Laib was also an artist who studied privately with Brockhurst during his time in America. Brockhurst’s images often seemed timeless, removed from social context. Other than the fashion, does this work evoke the era in which the artist made it?

Additional works by Brockhurst in the museum’s collection reflect similar compositions.

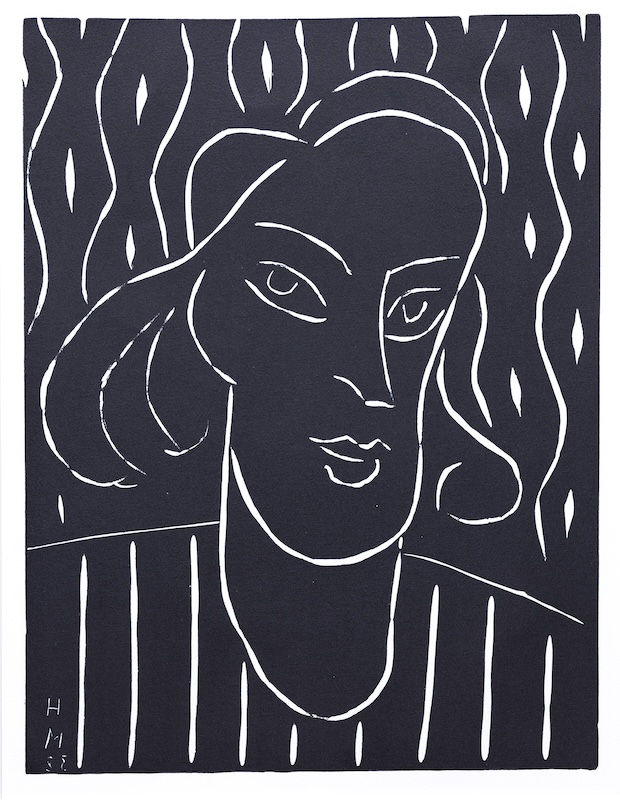

Portraits can reveal the inner character of the people that they show. The portrait of Alexina “Teeny” Matisse, by Henri Matisse, exemplifies this aspect of portraiture. Most portraits in this exhibition show the physical features of the sitter in detail, but not this one. Instead, Matisse creates only an outline of the sitter’s face, hair, and features. Because of this, she becomes one with the background and dominates the composition. Additionally, Alexina Matisse’s direct gaze reveals her inner strength, conviction, and sense of self.

Unknown Sitters

Traditionally, a portrait is a depiction of a particular individual, but what happens when the person is unknown? All of the works in this section show anonymous or unidentified sitters. Sometimes, a sitter is unknown because they were simply a model for artistic study. Other times, a portrait’s subject is intentionally anonymous to represent a broader population or theme. Many portraits involve a power dynamic between artist and subject. These works of unknown sitters, in particular, prompt us to think about themes such as gender, race, and class tensions. For many unknown sitters, these works of art are all they will be remembered by. If your identity were known only from a single portrait, what would you want this portrait to include? What would that artwork say about you?

The Victorian era lasted from 1837 to 1901, the years in which Queen Victoria ruled over Great Britain. These years produced great change around the world, especially within the world of fashion. This painting reflects the fashion of the late Victorian-era elite, with a high neckline, a tight corset and a small waist. Expensive details like the woman’s lace collar, silk gloves and the pale blue color of her dress indicate her high status.

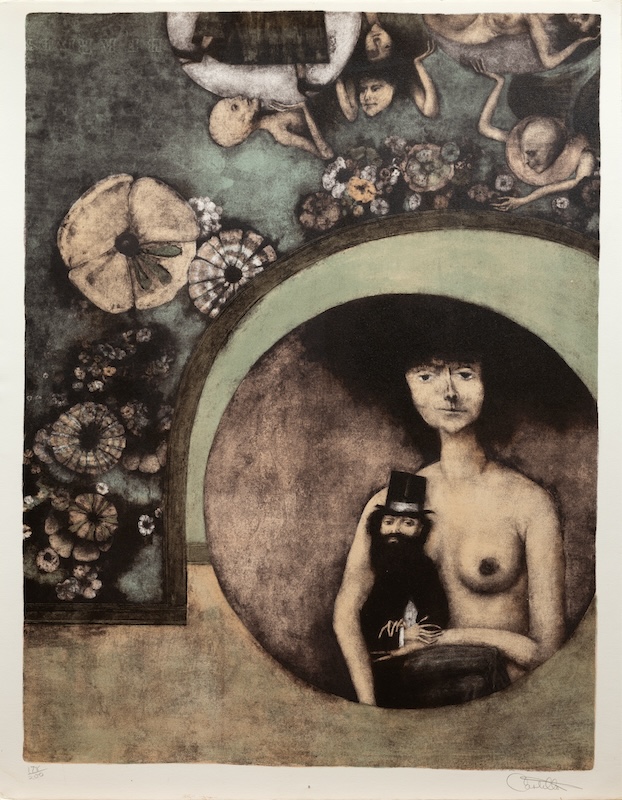

Federico Castellón immigrated from Spain to the US at the age of seven. As a child, he faced financial hardship and bullying but found sanctuary in art. Most of his family discouraged him from pursuing an artistic career, but his mother supported him. Despite these setbacks, he became a pioneering artist in surrealism, an artistic movement focused on the imagination and unconscious thoughts. Surrealists images often include confusing or unsettling imagery, as in Family Portrait. We don’t know much about the family in this print, but Castellón’s own history could provide an explanation. Who do you think this family was?

Jeremy Ayers was an artist and musician who grew up in Athens, Georgia. During the 1970s, Ayers participated in Andy Warhol’s Factory under the persona of Sylva Thinn. This portrait by Ayers shows a New Yorker wearing a beaded dress, glittering earrings, and a Star of David necklace. A mysterious, gloved hand reaches in to steal the reveler’s cigarette. The subject gazes directly into the camera lens, confidently meeting our eye. The Halloween setting prompts us to think about fashion as a means of self-expression and transformation. If you could become anyone for one day, what would you wear and who would you be?

Walther Günther Julian Witting studied the arts at Dresden University with other prominent painters of the time. He is famed for his landscapes and portraits, painted in oils. We do not know the identity of the model pictured in this drawing. The artist uses the negative space surrounding the figure by filling it with white a white gradient. This technique is also used as a framing device, making the model stand out against the background.

George Peter Alexander Healy (American, 1813 – 1894), “Portrait of a Woman,” 1872. Oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 23 1/2 inches. Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; The Mr. and Mrs. Fred D. Bentley Sr. Collection of American Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Fred D. Bentley Sr. 1987.103.

A renowned portraitist of his time, George Peter Alexander Healy was famous for painting important figures such as multiple presidents, King Louise-Philippe of France, and Pope Pius IX. He usually used dark, simple backgrounds. This painting, on the other hand, shows an unidentified woman who appears to be floating in the clouds.

Birdkeeping was a common pastime for the French aristocracy. Wealthy landowners kept aviaries full of falcons, hawks, pigeons, and other types of birds for hunting or personal accompaniment. Here, a young woman cares for her doves. A symbol of peace, love, and beauty, they reflect the qualities of the lady who cares for them.

Explore More Online Exhibitions

Want more? Check out some of our other online exhibitions.

Poems Inspired by Photographs

Andrew Zawacki’s Advanced Creative Writing (English 4803W) students participated in unique, challenging workshops centered around ekphrastic exercises inspired by photographs in the museum’s permanent collection.

What Are You Voting For? Light, Dark, and Truth in American Politics

“What Are You Voting For? Light, Dark and Truth in American Politics” explores the duality of politics.