Master of Fine Arts Degree Candidates Exhibition 2020

The annual exit show for the graduating master of fine arts students at the Lamar Dodd School of Art. Graduating candidates are able to exhibit their work in various areas of study including painting and drawing, fabric design, photo and video, printmaking, sculpture/fibers, jewelry/metals and ceramics. Due to COVID-19, this year’s show is entirely online.

Nick Abrami

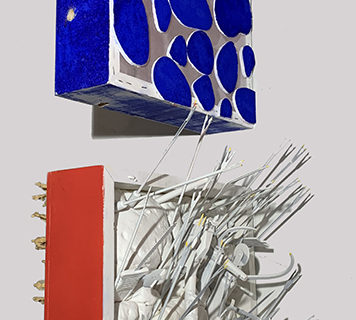

The vivid memory of the smell of fresh rain on hot pavement lingers in my mind when I wake up. Large forms are just behind my eyelids, and each time I blink and the dream slowly leaks out into the reality of my morning cup. I move through a space occupied by unassuming landmarks and wayposts that guide me home. Colors become distorted as I scramble to grasp onto a landscape that seems so familiar to me despite how foreign and displaced the objects in it appears. I attempt to orient myself amongst a constellation of strange, almost useless seeming architectures. There is a residue that sticks around even far into the day after the memory of the dream abstracts into barely a sentence’s worth of words. The structures fade and I return to now. This mithridatic practice of longing and losing is a daily manic cycle, these objects are created as an antidote to help guide me home. Lumbering blocks of color sit strong while lines and rods dart about capturing what’s just beyond their reach. I can almost smell it again . . .

Nick Abrami

“The Memory of a Dream About a Place” (unfinished)

Ceramic

62 x 48 x 28 inches

Nick Abrami draws inspiration from his subconscious, using his dreams and memory as a means of understanding the passage of time. Working with clay, he utilizes the physicality of his medium to concretize the abstract. His current work consists of an assortment of over life-sized, ceramic sculptures, modeled in the form of abstracted, geometric and curvilinear structures adorned with rich blue, red, and yellow glazes. Although seen as independent objects, they are meant to be experienced as a cohesive unit that challenges the viewer to reconcile the abstract, the real, and the imaginary.

Abrami works in conversation with his material, reacting to the clay as it responds to the movements of his hands. This process results in abstracted, almost skeletal forms, and lends the clay a life-like quality, reminiscent of the dream state where consciousness can be housed within the inanimate. Yet, this organic sculptural process also has ties to reality, mimicking the natural patterning and lattice work of Cypress roots. Hence, these forms make concrete references, even as they appear abstract and are, themselves, abstractions of imagistic dreams. In a poem related to this body of work, The Memory of a Dream About a Place, Abrami writes: “There is a residue that sticks around even far into the day after the memory of the dream abstracts into less than a sentence’s worth of words. The structures fade and I am evermore entrenched in the now.”

The organic progression of his sculptural work presents itself as the ‘residue,’ or latent memories of the natural, physical world – i.e. the Cypress root interpreted ‘in the now’ as an abstracted form constructed from fleeting memories.

The natural forms of Abrami’s work complements his experimentation with the effects of light and shadow; arches and negative spaces within his lattices become passageways for light to travel. If viewed outside over the course of a day, Abrami’s sculptures become abstracted sun dials that disrupt conventional notions of time, as one shadow fades into the other, leaving behind the “residue” of our collective understanding of time. On the surface, the light is combated by the rich, vivid primary colors that serve to reflect the quality of Abrami’s dreams. He again writes: “I make these awkward, lumbering, hued structures as an antidote for incessant yearning and as a guide back to a familiar place. Substantial blocks of color ground the lines and rods that dart about reaching for what is just beyond their grasp.”

His use of intense coloring, paired with the abstract formations, and over life-sized scale seamlessly signifies his desire to merge the abstract with the real, urging his viewers to contemplate with him as he rests somewhere in between.

David Campo III is a second-year MA candidate in art history at UGA. He received his BA from the University of Florida in Gainesville, FL, where he majored in anthropology (concentration in archaeology) and minored in classical studies. He analyzes the history of art collecting and management, and he is interested in investigating how art serves as a form of material culture and is studied within the context of the museum.

Yana Bondar

Gentle Sadness: It’s a feeling like the quiet hum in your heart before you start to cry but suspended indefinitely; kind of like sleeping, kind of like rotting.

My work explores this sense in the context of resistant apathy through multiple perspectives of femininity (Catholic Femininity, Toxic/Self-Destructive Femininity, ‘eternal’ Girlhood). I explore this intersection of individual and collective identities in my work by isolating and emphasizing narrative archetypes from various sources ranging from biblical to contemporary commercial medias and toy franchises. The figures in my work exist in full awareness of their composite identities; built for an ambiguous agenda, yet apathetically acknowledge that they can never attain their own agency or personhood. They exist for a purpose or service, as sacrificial vessels, but in reality there are many parallels to the narrative and cultural identity of Catholic Womanhood.

Narratives are written to offer guidance and modeling through life. Writing a narrative is both a constructive vision of future and an ethical dilemma. When a narrative is created, whom is it created for and what consequences will it bring into the world? Mystery is one of our greatest fears yet it exists in every aspect of our experience. We try to mediate it through ideations, changing a confusing gradient of events into black and white distinctions. I channel this through various feminine forms that exist as archetypes rather than characters, exploring isolated feminine interiority in anachronistic material reverence with a contemporary perspective.

The context and conceptuality of my work is currently being expanded to include social practice and community participation through ritual performance and online engagement. Through bringing others into performances of my own personal narratives, I intend to gain a deeper understanding of how we as individuals collectively propel ourselves through day-to-day existence. By donning an identity outside of myself and outside of the roles that exist in cultural collective consciousness, I actively give up parts of my humanity in the public space. That with no assigned role is like a ghost, that with no simplified identity is too difficult to understand, that with no connection to – (generalized, collective) ME – is not fully human until a connection is built.

As it stands currently, my practice is in a between stage of transition, instigated by core approaches to engage the present-future rather than the past-present/past-future. This specific transition requires unambiguous negation and re-emersion/negotiation of material, narrative, and presentation. The ability to speculate future with honesty and aspirational precision is part of experiencing life as a -real- person; a way of experiencing with impact, agency, and ownership. No longer is the voice an echo, a whisper nor will one’s hand pass through the door. Everything suddenly matters a little more. Having built a practice before I became real (September 2018), I have had to reestablish what it means to make (or not). My work does not have to make me feel – real – anymore but perhaps one day it may also desire to become – real – too.

Three large-scale ceramic nesting dolls lay alongside one another in coffin-shaped beds, their slender, youthful bodies a curious amalgamation of ideal, female form and grotesque, skeletal appendages. Each figure contains smaller dolls, exposed to the viewer through compartments — the heart, pelvis, and face revealing romanticized narratives that ambiguously guide and unify Yana Bondar’s mixed media collection. Like the anatomical Venuses of the eighteenth century, these figures exist within the confines of their projected roles in society. While the Venuses were modeled on popular Renaissance ideals of sexualized femininity, their bodies tools to be invaded, Bondar’s porcelain dolls represent a corruption of those virtues—manifesting the toxic reality of archetypes presented as universal truth.

These works are inspired by Catholicism and shōjo* anime, both of which privilege young feminine virtue and eternal girlhood. In Catholicism, many feminine ideals are modeled through the Virgin Mary whose identity is defined by her virginity and role as vessel for Christ. In Renaissance tradition, she is often depicted as young and beautiful, a physical manifestation of her eternal purity. In contrast, shōjo narratives uphold female paradigms that focus on interpersonal relationships and emotional intelligence, allowing figures to learn and grow as individuals. By pairing her ceramic dolls with clerical tapestries decorated in shōjo aesthetics, Bondar merges these cultural archetypes of femininity as a way of exploring her own identity as an Asexual, Aromantic, feminine person with a Catholic upbringing. For Bondar, employing these aesthetic cultures allows her to subvert traditional biblical iconography that intimately connects female virtue with motherhood. Instead, Bondar enfolds the emotional veracity of shōjo models with traditional materials associated with the divinity, wealth, and power of conventional Catholic art.

Bondar describes her dolls as “sacrificial vessels,” the layering of large dolls and miniatures evoking the multiplicity of roles created for young women in contemporary society. The narratives constructed by the small figures seemingly perform a dual purpose—suggesting the potential pathways to a less abstract existence while they simultaneously fracture the vessels they embody. While the dolls can never attain their own personhood, their presence is an ambiguous commentary on the fragmentation of feminine identity—a momento mori of the life that could be, had they the agency to be their authentic selves. Each doll references a form of martyrdom—sacrificing body and mind to the service of others. Just as the Virgin Mary is identified by the child she carried, so too are Bondar’s dolls—their names defined by those nestled within them, their bodies corrupted by the roles they attempted to fill. In The Trinity, the doll’s physicality decomposes as she serves as a vessel for others, her chest dissected and limbs an ashen grey. The central doll is the most corrupted—her legs and belly have ominously blackened and her pelvis has disintegrated. In its stead lie The Lovers, Death, and Disease—consuming the fate of the doll’s obliterated body. The last doll, Becoming Real Again, suggests melancholic hope—her arms and legs only partially decayed as her face reveals a pair of miniature figures. Through Bondar’s vessels, the toxicity of female paradigms is laid bare, just as they are simultaneously reimagined—their ambiguous agenda hinting at reconciliation of divinity, femininity, and salvation.

* shōjo or shoujo describes a genre of Japanese visual culture catered primarily to young girls, typically characterized by their focus on personal relationships.

Megan Neely is a doctoral candidate at the University of Georgia, where she also received her MA in 2015. Her current research addresses the social status of artists, their self-portraits, poetry, and mythological punishment in sixteenth-century Venetian art.

AC Carter

AC Carter is a musician, performance artist and garment designer who creates characters through music, internet profiles, outfits, video and quasi-marketing-strategies. Their main protagonist is Klypi, a wanna-be pop star who performs music that can be modern alt-pop inspired by 1980s pop-rock and early 2000s industrial. The other supporting roles in relation to Klypi are Lambda Celsius (Λ°C), the genderless fashion brand who acts as Klypi’s personal stylist, and Vixcine Martine, a doctoral student at UGA writing her thesis on Klypi.

Through these characters, AC investigates ideas about love, gender deviancy and authenticity and challenges the idea that the individual is singular, rather than multiple in design. Identity is tied to the body both physically and virtually; it is a continuous site of construction and can be understood as both a building and a web page. As a musical artist, Klypi is a self-identified elf, hoping to expand our ideas beyond boy and girl. As Λ°C, AC foregrounds the notion of fluid identity by thinking of materials and bodies as non-gendered — interpreted as shape, color and form. And as Vixcine Martine, AC challenges ideas of what humor, sexuality and intelligence can look like from a feminist perspective, hoping to play with how to navigate and scholarly reflect upon their other selves.

As a musical performer, AC has opened for artists such as Molly Nilsson, John Maus and Girlpool and has performed at Big Ears Festival, Athens Popfest and Secret Stages.

As a fashion designer, AC has made garments for Jennifer Vanilla for her performance at MoMA PS1, and for the band of Montreal for their music video “Plateau Phase-No Careerism No Corruption.”

Last, AC also curates and organizes Ad•verse Fest, a festival in Athens, Georgia, for solo and duo performers cross-genre underscoring DIY experimental and electronic scenes in the South and across the continental US.

Klypi

“I’m Fine,” 2020

5 minutes, 19 seconds

Directed + edited: AC Carter

Cinematography: Sara-Anne Waggoner

Head assistance + on-set direction: Lindy Erkes

Light assistance: Lindy Erkes, Jordan Stubbs, META

Smoke: Lindy Erkes

Styling: Lambda Celsius (Λ°C)

Make-up: Katelyn Bass and Molly Maxwell

Animations + text design: AC Carter

Additional photography: Sara-Anne Waggoner

Filmed at Studio 104 at Thomas Street Art Complex

Actors

Starring Klypi

Dancers: Mac Balentine, Sara Black, Yana Bondar, Luka Carter, Courtney McCracken

Love interest: META

Smoke director: Lindy Erkes

Make-up artist: Molly Maxwell

Starring AC as Klypi

Written and recorded by Klypi and Precious Child

Song produced by Precious

2020

Klypi, “Get Over You,” 2019

3 minutes, 30 seconds

Director of photography: Precious

Edited: AC Carter

Light + smoke assistance: Lindy Erkes, Kira Hynes, Sa Bo

Styling: Lambda Celsius (Λ°C)

Make-up: Precious

Animations + text design: AC Carter

Filmed at The Finishing School at Thomas Street Art Complex

Written and recorded by Klypi and Precious Child

Song Produced by Precious

2020

Klypi, “Not For You,” 2020

4 minutes, 24 seconds

Directed, shot + edited: Casey Pierce

Make-up + assistance: Rian Archer

Styling: Lambda Celsius (Λ°C)

Filmed at BY TOURNAMENT in Nashville, Tennessee

Starring AC as Klypi

Written and Recorded by Klypi and Precious Child

Song Produced by Precious

2020

Fascinated by ideas of love, authenticity, identity, and gender, artist AC Carter creates characters that challenge the idea that subjectivity is singular. A musician, performance artist, and garment designer, Carter brings these characters to life through internet profiles, costume, music videos, and advertisements. In this way, the artist navigates the fluid lines of gender and love and expresses different, non-conforming perspectives.

Carter’s primary character is Klypi, a self-identified house elf and wannabe pop star. Klypi stars in all three of Carter’s music and performance videos—“I’m Fine,” “Get Over You,” and “Not For You”—all of which force viewers to think beyond the rigid cultural distinctions of male and female, as elves do not have a specified gender. The music sung and produced by Carter’s gender-bending elf can be described as a form of modern, alternative pop that takes inspiration from 80s pop-rock and early 2000s industrial music. In the video “I’m Fine,” Klypi interacts with others as they attempt to understand the importance of love, while in the music videos “Get Over You” and “Not For You,” Klypi reflects on the concept of authenticity and the status of specific relationships. Klypi’s identity is further refined through social media and advertisements. By establishing a web presence for this character, Carter highlights identity as a site of construction. For Carter, the body is tied to identity both physically and virtually, and creating an online presence for Klypi foregrounds the idea of identity as a performative work in progress; just as someone builds a webpage, so Carter builds identity for Klypi using the body and clothing as material.

Lambda Celsius (Λ°C), garment designer and personal stylist to Klypi, is yet another persona developed by Carter. Lambda Celsius has developed their fashion brand by utilizing construction materials, craft materials, and gender-neutral toys such as Legos to abstract Klypi’s body and reinforce gender fluidity. Through Lambda Celsius, Carter produces fashion beyond the expectations of societal norms, which then appear in Klypi’s videos. The clothes force the viewer to focus on shape, color, and, form and reduce the body to unsexed lines. Lastly, Carter offers a feminist perspective on gender and sexuality through the figure of Vixcine Martine, a PhD student who is writing their thesis on Klypi. Through academic research, Martine analyzes Klypi and Lambda Celsius, reflecting on the identities of these characters. This character allows Carter to assume a certain distance from their other personae, since they use the intelligent Vixcine to assess how ideas of humor, sexuality, and gender, operate in the Klypi’s multifaceted world.

Charlotte Gaillet is a first-year MA candidate in art history at the University of Georgia and received her BA from UGA, where she double majored in art history and political science. Gaillet’s research examines 19th – and 20th-century American art through a political and gendered lens. She serves as an intern at the Georgia Museum of Art where she works with decorative arts and material culture.

Cristina Echezarreta

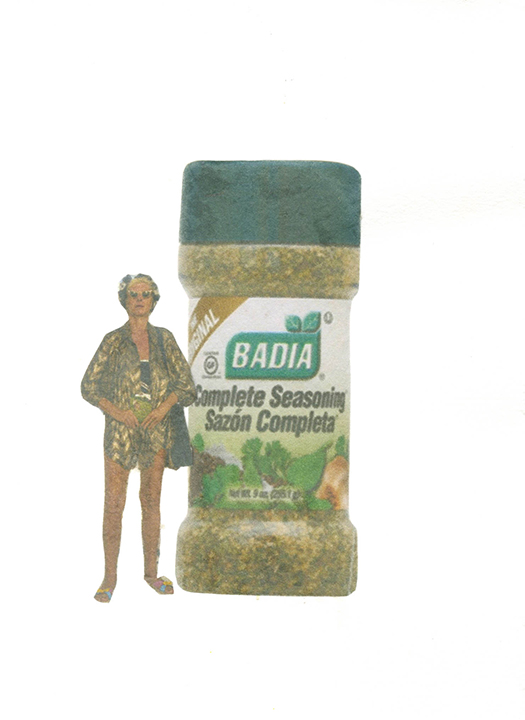

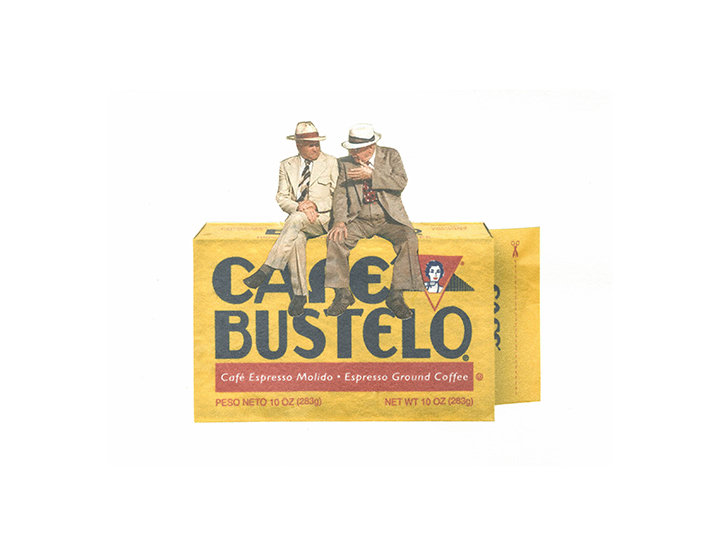

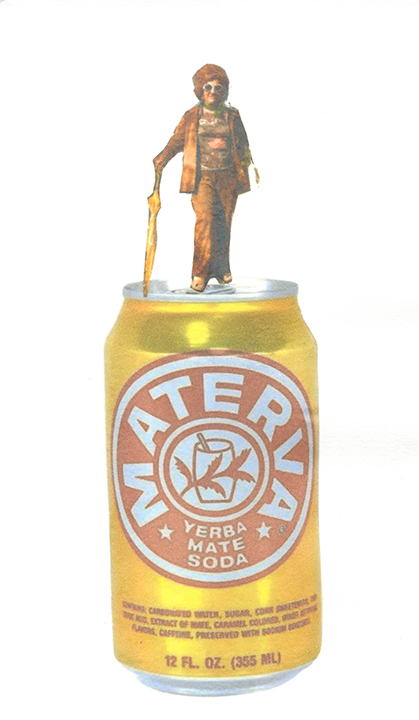

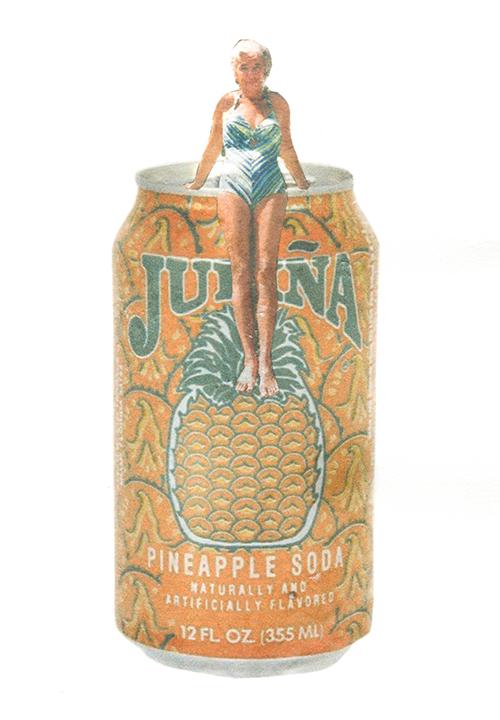

As a second generation Hispanic-American raised in Miami, my daily life was filled with Spanish-American items and products that influenced my ideas of what it meant to be an American. Sazon Completa, Goya, Pilon and Jupiña are all products that have filled the shelves of my upbringing.

These objects are readily available in Miami, and are clearly a subset of American consumer culture. They function as relics and reminders of the past for the older members of my family, and because of their familiarity and stagnant visual appeal, they produce a sense of comfort and belonging within a new country. Yet, for those of us born later, on American shores, such as myself the relationship between the product and person thickens. Though they function as comfort for my family members, for me, these products instead function as a staple of both identity and consumerism.

Material culture allows us to identify ourselves with such products, which in turn affects how we view ourselves in comparison to the world around us. Aspects such as advertisements, marketing and consumerism are all explored within my work. In order to understand my identity I must seek the interactions within my culture and lifestyle.

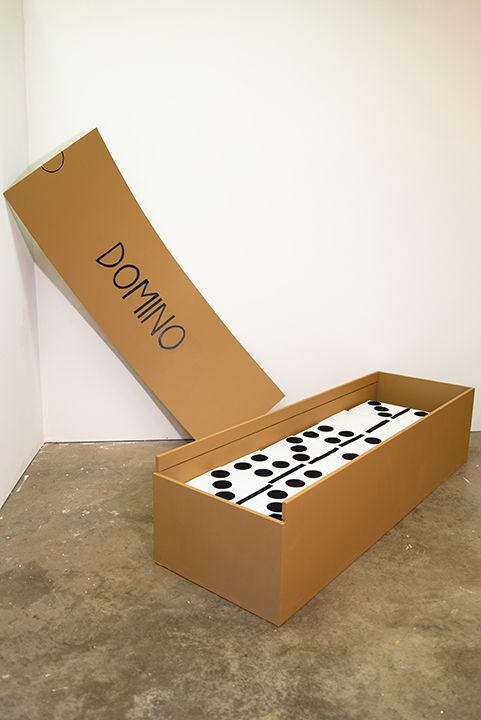

“Doble Seis Dominós (Double Six Dominoes)” is inspired by the reoriented Cuban culture that exists in Miami, Florida, today. The history of Cubans migrating to Miami dates back to 1959, when Fidel Castro came to power, and continues today. In order to find comfort in a newfound land, older Cubans spent their pastime playing dominos and have passed it down to younger generations. Dominos have become a staple of Miami material culture and impacted the Cuban American experience.

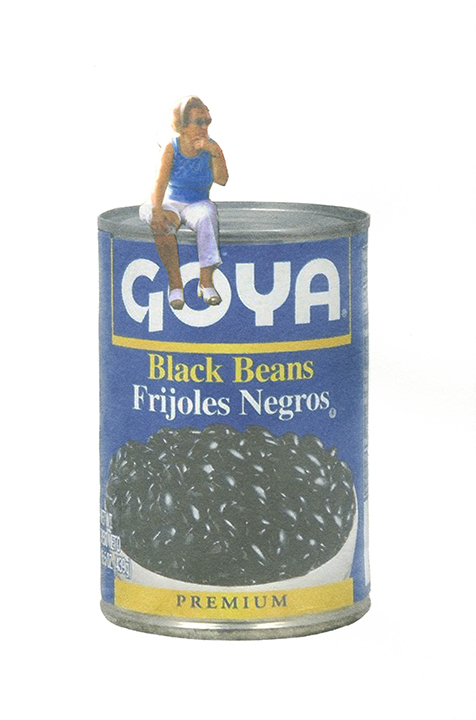

Cristina Echezarreta was born in Miami, FL, a place known for its booming tourist industry and for being home to many migrant Hispanics and Hispanic-Americans. As a second generation Hispanic-American, she investigates the entanglement between tourism and her closely connected, Hispanic community from a multi-generational perspective. For Echezarreta, the two are intrinsically connected through the spirit of “community” and are best understood through the material culture they produce. Her current work, which takes the form of whimsical prints of Hispanic individuals and products, along with an over-sized domino set, explores how material cultural is used to construct identity as it relates to her Hispanic heritage.

Echezarreta stumbled on the documents of American photographer Andy Sweets, found in the Florida archives, that contained pictures of elderly individuals basking in the charms of Miami beach in the 1960s and 70s. This gave her the idea to create a series of prints that depict her grandparents and other elderly Hispanic-American individuals posed with various Hispanic products. Consider, “Galleta Guys,” for example. The fantastical, comedic difference in size between person and commercial object emphasizes how these everyday items truly shaped the Hispanic-American identity and formed a new landscape. Moreover, when viewed by a Hispanic audience, these mundane items functioned as small time-capsules, transporting the viewer to specific moments and places in time. “Vaporu Vieja” conjures up memories of Hispanic grandparents and parents swearing by the cure-all properties of Vicks, and “Fabulosos” reminds most Hispanic children of the early weekend mornings where they cleaned for hours on end. For Echezarreta, she is reminded of how the “traditional” uses of these items were passed down from her grandparents, her parents, and then herself, shaping her Hispanic-American identity. She succeeds in drawing out meaningful memories in the subtlest of ways and continues to stress her devotion to the community and a communal identity.

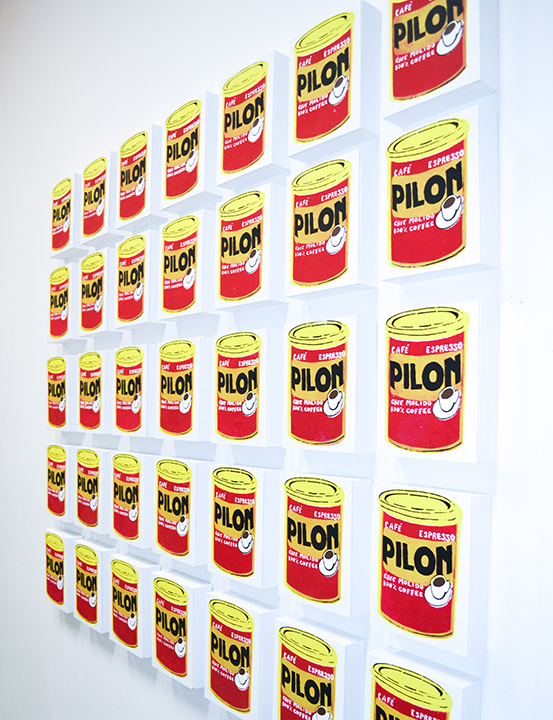

Echezarreta continues her exploration of material culture and identity through her installation, “Pilon (35 Cans).” Depicted on thirty-five silkscreens are printed cans of a brand of coffee very popular in Hispanic households; however, Echezarreta also references Andy Warhol’s 1962 “Campbell’s Soup Cans” via her format and medium. This strategy draws the attention of non-Hispanic viewers who will recognize Warhol’s signature format, thus exposing them to a staple beverage consumed by Hispanic peoples. The idea of coffee and coffee culture, however, is transcultural and Echezarreta uses that to her advantage, in yet another subtle manner, to establish communal connections within and outside of Hispanic-American communities. The image of the Hispanic coffee brand within the museum also allows those in her own culture to feel represented and empowered to occupy such intimidating settings.

In a more grandiose manner, Echezarreta’s over life-sized sculpture titled “Doble Seis/Double Six” embraces absurdity and humor. The over-sized dominos conjure a common game played by Hispanic and Caribbean peoples, yet, they invade the viewer’s space and force them to confront her culture in a playful fashion. When playing dominos, the person who draws the double six starts the game, and in a way Echezarreta places her culture at the fore and requires an immediate response from the viewer in a way that is always inviting. Games, like coffee, are transcultural and communal, allowing individuals from diverse cultural groups to establish connections through common ground. Dominos also strongly evoke specific memories in a very playful manner and serve as a reminder of how Hispanic families would spend time together.

Echezarreta has ended her MFA career exploring the last place she could imagine, her hometown of Miami. Heavily influenced by her community and family, she seamlessly utilizes the power of material culture to educate the uninformed about Hispanic-American culture, while also telling her own story. She pays homage to those who have come before her through comedic prints of elderly Hispanic individuals posed with Hispanic products and over life-sized games and repeats the advice of her father to, “Never forget where you come from.”

David Campo

Christina Foard

One person interrupts, another person avoids eye contact. One person laughs at a crass joke, another person deflects accolades to credit someone else. A tone shifts, an omission is registered. Around the dinner table, a drama unfolds – at once a scripted performance of prescribed roles and an improvisation, in which identities are tweaked and resisted, food and ideology is consumed. In this post-Trumpian era, the American family table becomes a localized stage for covert and overt petitions for power and a landscape for polemic disputes.

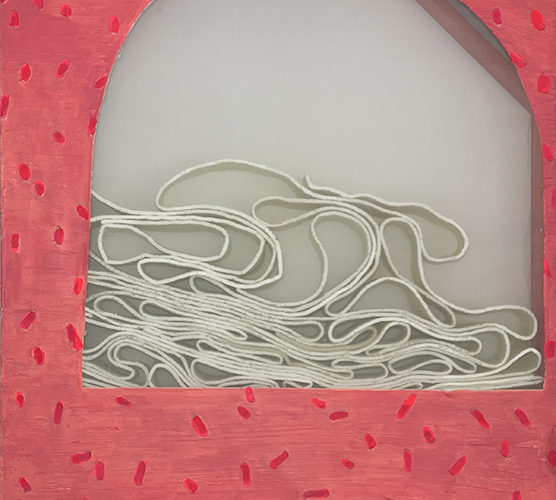

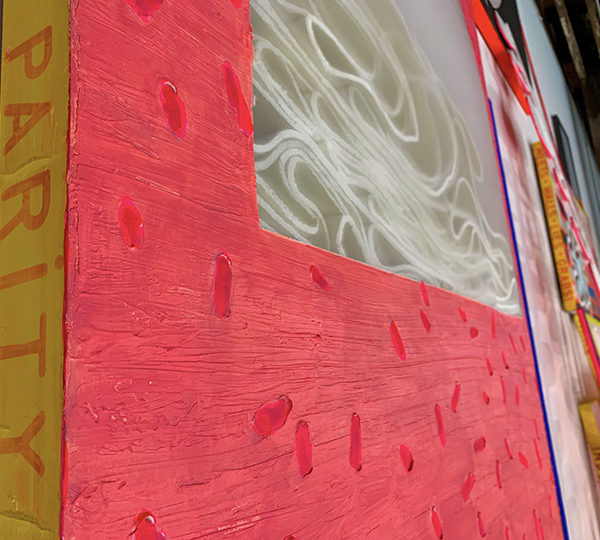

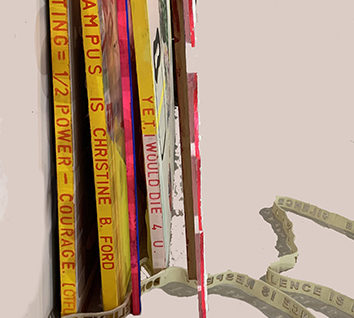

My installation consists of wall and floor-based objects made of painted wood, wire, felt, foam and silk, each engaged in competition for attention through positioning, scale, color, and layering. Themes of opacity, transparency and temporality are referenced through their material construction. Plant-forms, vessels, children’s toys are inferred as components of a deliberate, semiotic language native to domestic interiors and the kitchen table theater. Embedded into the works are words and dialogue relevant to the events that cascade into the #metoo movement as a central topic of discussion at the table. Geometric blue pigmented sculptures serve to cluster objects as an imposed structure among the plurality of competing voices.

Christina Foard’s large-scale, mixed-media installation, “In the Cacophony Of Voices At The Table, I Only Remember What Wasn’t Said” (2020), was sparked by deep engagement with the Brett Kavanaugh Supreme Court Nomination hearing, particularly Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony in which she accused Kavanaugh of sexual abuse decades prior during their high school years. Ford’s testimony led to conversations around the kitchen table among Foard and her family, and it was this, and other similar occurrences such as the Brock Turner rape trial, that marked both the beginning of the #metoo and #timesup movements and inspired Foard’s installation.

Foard’s installation consists of 14 individual objects ranging in size and material. Together, they highlight the rhetoric and polarization that occurs among families when discussing sensitive topics. Through the incorporation of personal objects as symbols, Foard creates a codified narrative and because she arrangers her objects and sculptures in a cyclical pattern, her installation calls to mind the often-repeated circumstances and experiences of women like Blasey Ford.

The circle of objects begins in the bottom-left with a painting entitled “2018 Celebration.” On the left side of the canvas, Foard includes one of several “peripheral statements,” an informal, tweet-like message, which appears on all the wall-mounted objects. The statement assigned to “2018 Celebration”—“You Can’t Laugh and Feel Fear At The Same Time”—works in tandem with the image of a table prepared for a party, with the cake on a stand in the center. The sentiment expressed in Foard’s peripheral statement about mixed emotions creeps into the painting, through the repeated strokes of color along the left and top edge of the canvas, as well as the swirl of blue underneath the table, hiding, unseen, akin to the way anxiety and fear can creep up during what should be happy times.

The cycle continues upward to a painting entitled “Don’t Touch,” with peripheral statement “Don’t Touch. It’s Our Parity Party.” The center of the canvas has been cut out in an arch shape, with a long strip of felt stacked within the cut away space. The arch feels to Foard like an opening to an interior or exterior space. The shape takes on its own persona, while the red, felt lines in the interior space of the canvas read as moments of anxiety created by chronic, pervasive sexual harassment in the workplace. The statement on the side sounds off as a statement of power, of wrestling back control of a workspace by excluding harassers from the attempt to gain equality of status and pay. Continuing counterclockwise, the installation comes to an end with “Silence Spillage” and “Word Garbage.” “Silence Spillage” is a length of felt made entirely of Foard’s peripheral statements such as “Silence Can Be About Shame and Power,” “Silence Can Be About Fear,” “Silence Can Condone Abuse,” “Think About What You Say,” “Think About What You Don’t Say,” as well as many others. This, too, is arranged in a circular manner, again calling to mind the cycle of silence that is prevalent in regard to experiences of sexual abuse. The final object of the cycle, “Word Garbage,” is a circular piece of wood that resembles a plate with letters in a pile on its surface. By labeling the wooden letters “garbage,” viewers are encouraged to imagine that these are the words that are never said in relation to the “silence spillage” nearby. In this way, Foard suggests that, oftentimes, significant words are left unsaid for so long that they are eventually thrown out and disregarded, perpetuating the cycle of silence.

Ashlyn Davis

Laurel Fulton

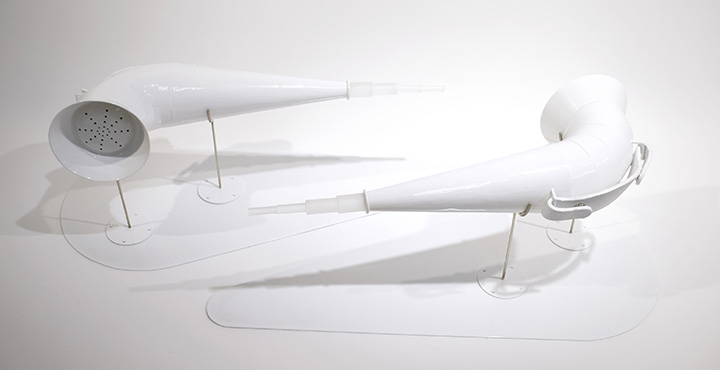

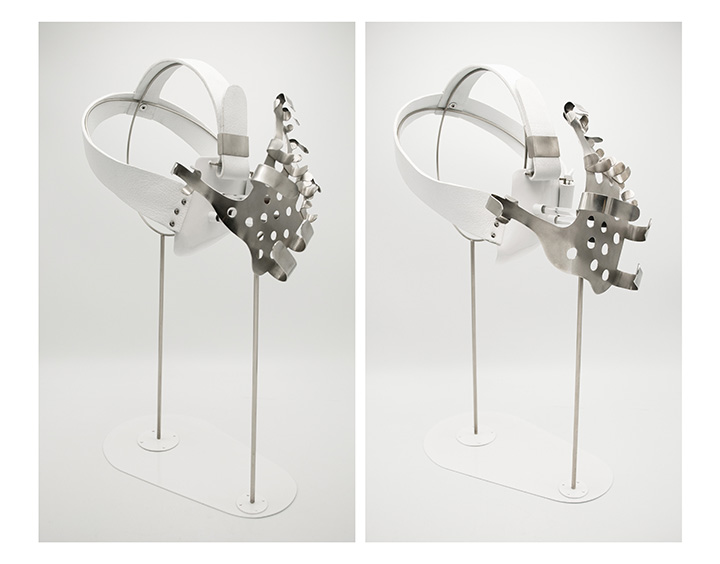

The objects I make are best understood as braces that suspend bodies in relation to one another, often in close proximity: a hand held inches from the face, or two chests attached to each other, but suspended at an insurmountable distance. As typically understood, moments such as these are only stages on the way to other, more iconographic moments: the embrace, the kiss, the caress. But, in my work, these overlooked moments come to visibility in their own right, and through them I bring attention to our desire to connect with one another and our inability to do so in a way that could satiate us.

These ideas are played out when the viewer sees the objects both unoccupied and occupied, either through the objects themselves and images of the objects on the body. In either case, the spectator is encouraged to contemplate his or her own embodied experience. My work forces people to communicate through the body, often mimicking the body of another. But, in making visible the space between people, I create a contradiction between what we what we say we desire and what we achieve. We claim to want complete connection and communion with someone yet if it were possible to attain it, would it satisfy our desires? The great cost of our fulfillment would be a collapsing of two entities into one and an erasure of the individual. The objects I have made, make visible the conflict we have with desiring someone and the inability to have them. It is through the object that I mediate, and make physical, the experience of desire that is unseen. Never reaching it and forever seeking it are the only absolutes in want and desire

Take your hand and run your fingers through your hair; tousle it the way that a loved one used to. Perhaps your face flushes with the memory of sexual desire, or perhaps your anxiety calms as you remember how a parent once fixed your hair. Embedded within sensory experiences are memories, which, once repeated, can ignite physical reactions and feelings. To experience humanness is to feel connected and understood, and the bodily senses, including touch, smell, sight, sound, and taste, often shape our emotions and desires more forcefully than spoken language. In her wearable sculptures, Laurel Fulton explores the embodied nature of human interaction, communication, and connection.

As a jeweler and metalsmith, Fulton’s work is intrinsically concerned with how humans construct meaning through objects, and how adornment constructs meaning for humans. At the beginning of her MFA career, Fulton focused on the historical use of apparatuses for medical practices and body ornamentation, so it is perhaps no surprise that Fulton’s wearable sculptures are both clinical and aesthetically beautiful. Most of her multimedia works are made of leather, plastic, and metal, and resemble medical instruments from a doctor’s office, like back braces and finger stints. Essential to her apparatuses, however, is the interaction between two wearers. In “Immeasurable Distances,” two belts, both attached to a metal and plastic body device that goes over the shoulders, wrap around the waists of two bodies. These braces are connected by two support beams that jut out from the chests and pelvic regions of the wearers linking the erogenous and reproductive zones. Hence, the apparatus potentially visualizes the sexual desire felt between the two bodies; however, it simultaneously creates distance and forms a barrier that prevents the bodies from establishing a physical connection. At the same time, it induces a form of paralysis, perhaps reflecting a form of codependency that can be physically and emotionally toxic.

Her work “An Almost Collapsing of Bodies” consists of a head piece that covers the mouth, to which is attached a metal hand-brace that suspends another figure’s hand. Here, one figure, unable to touch, cannot find comfort from the other, who is likewise unable to speak. “The Silence of a Kiss,” also worn by two figures, resembles head gear you might find at an orthodontist’s office (or a BDSM closet). It connects its wearers at the mouth by a metal tube—a kiss wanted but never granted. In “To be Seen,” two figures hold a clear tube that resembles a periscope turned on its side and are encouraged to peer through both ends seeking each other’s gazes. Yet, the apparatus allows only for a voyeuristic experience and precludes the kind of sustained, face-to-face looking common to lovers. In channeling these interlacing sensory experiences and disrupting them through wearable objects, Fulton focuses on and thwarts the human desire to experience meaningful, physical connection. Yet, Fulton’s apparatuses do not necessarily create space; rather, as the artist suggests, they make distance visible. Likewise, in quarantine, the real and constructed spaces between loved ones, between memories, and between bodies has become more apparent. As we continue to communicate through computer screens and remain six feet apart, our desire for physical, sensory experiences and communion increases exponentially. Perceiving Fulton’s work now, as a disembodied viewer, amplifies what is ever present, but currently exacerbated by circumstance: man’s longing for touch and understanding.

Jordan Dopp is a second-year PhD Student of art history at the University of Georgia. She received her MA in art history from UGA in May 2018 and her BA in art history in religious studies from Furman University (Greenville, SC) in 2015. Her master’s thesis addressed the aesthetic relationship between painted “Fayum” portraits and mummy cartonnages from ancient Roman Egypt. Currently, Dopp is studying ancient adoptions and adaptions of Greco-Roman style wall paintings in Petra, Jordan, and its environs.

Mary Gordon

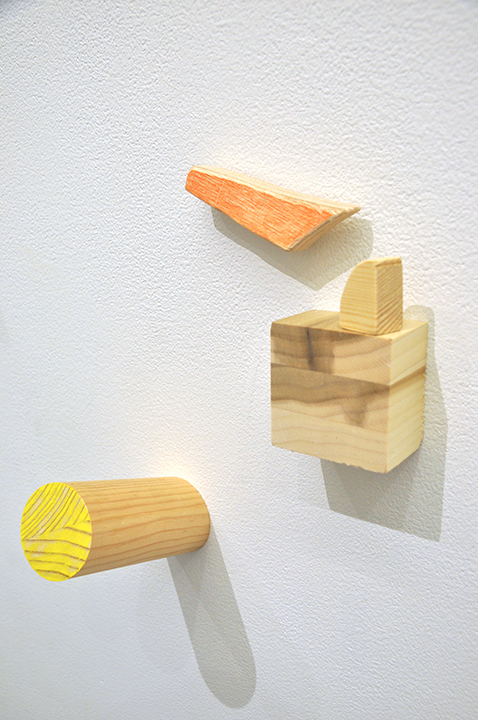

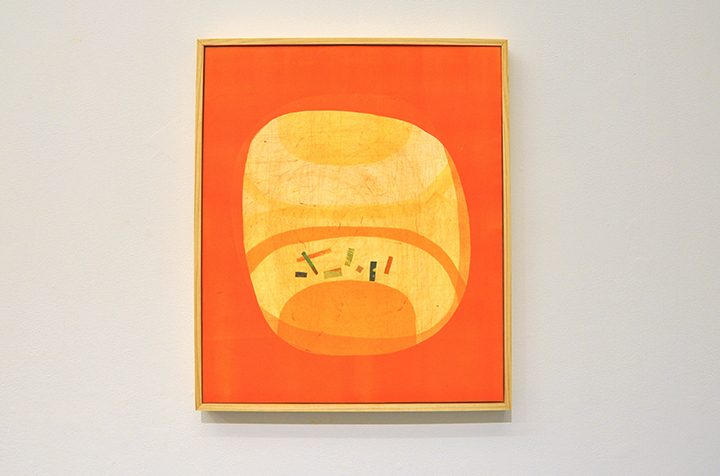

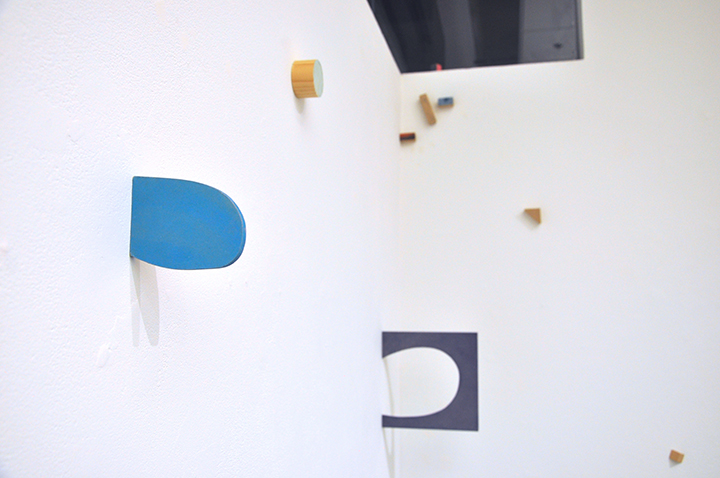

“What does play mean?” One thing it means, according to David Arron, is the sense of inspecting, turning, holding to the light and examining all the possibilities of something. “We speak of playing with an idea, meaning we look at it every which way.” In this sense, I play with ink, wood and paper to explore place through gestures of drawing, carving, assembling and balancing. In my creative practice, play is a methodology for making, as well as a lens for observing the world.

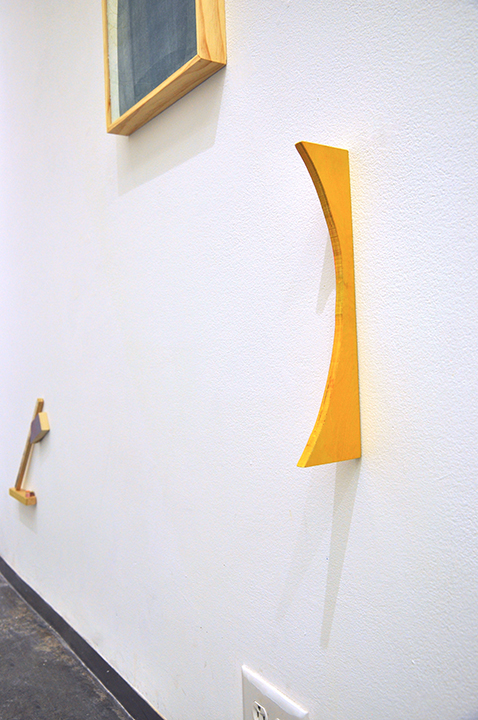

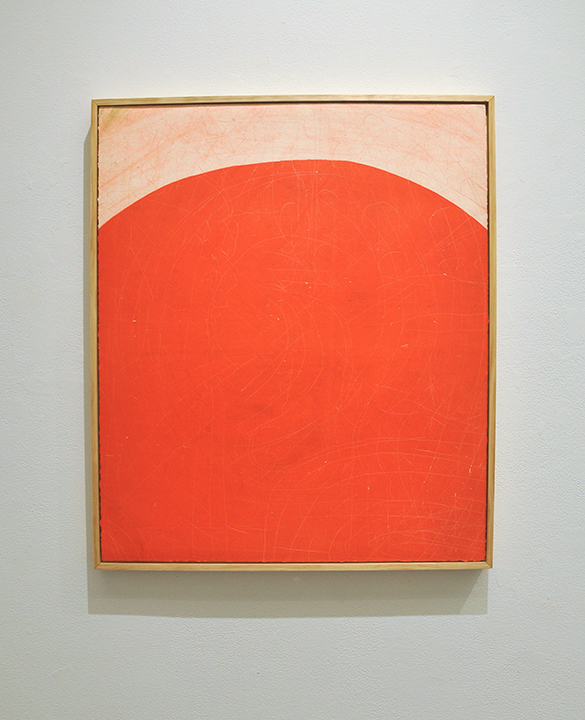

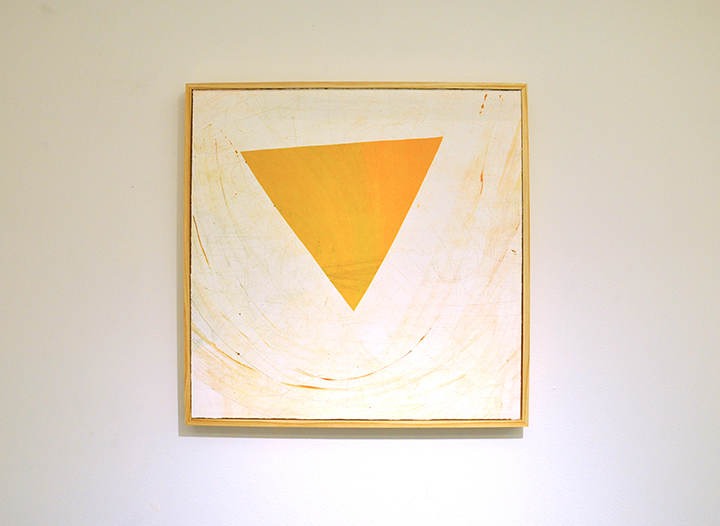

My thesis body of work includes monotype prints and provisional wooden blocks dispersed and assembled along three walls. Familiar forms stack, fall and climb, oscillating between two and three dimensions. Shapes become personified characters, the aerial view of a landscape, the close-up of a pebble, the top of a mound; they are symbols to sketch deeper meaning, and elements to turn and hold to light.

Mary Gordon is a sculptor and printmaker whose assemblages incorporate wood-block pieces of various sizes adhered to and protruding from the wall. As material, these wooden blocks emphasize child-like manipulation, encouraging the idea that the artist held the object, feeling its texture, turning and viewing it from all angles before placing it not only where it is best situated, but where it is most visually pleasing. Installed in the gallery or home, these blocks interact with their surroundings in unexpected ways and are balanced on or framing preexisting thermostats, light switches, and exit signs. Forming ellipses, triangles, and serrations not only in physical, three-dimensional form, but also as ephemeral, two-dimensional iterations in shadow, some blocks are securely fastened in place, while others are merely propped, resting on and against one another. Poised precariously, the stacking of installation components emphasizes the spontaneous and the uncertain. The assemblage as a whole rewards close up and distanced viewing which allows the viewer to intuit the artist’s investigation of the blocks’ myriad possibilities.

If all this is reminiscent of child’s play, that is because, for Gordon, “play” is, most simply, the manipulation and inspection of something with the intention to determine all of its possibilities, uses, and potentiality. The gesture and tactility of engaging with objects is significant to her work. It is in this manner that Gordon plays with medium. She utilizes ink, wood, and paper to explore a variety of techniques such as drawing, carving, and assemblage. For Gordon, play is not only key to her methodology, incorporating both the deliberate and the spontaneous, but also a way of observing and engaging with the world around her. She records textures, colors, and patterns found in both the artificial and natural world, and experiments with them through physical handling and layering. Gordon believes that printing and sculpting allow for certain aspects of uncertainly and even surprise. Gordon’s surroundings, and her experiences within those surroundings, be they natural or man-made, form the basis for her inspiration. It is by looking, recording, and physically engaging with the world that Gordon is able to create her instinctive monotypes and assemblages.

Responding actively to space, her sculptures work with and against gravity to find balance, much as her monotype prints are suspended or balanced within a frame. Surrounded by monotypes in an array of unrepeating colors and common shapes, the colors, shapes and patterns within the prints simultaneously engage with, mimic, and reject the colors, shapes, and patterns utilized in the woodblock assemblages. The prints are not only flat, two-dimensional representations of the three-dimensional shapes, but they also, through juxtaposition, exemplify and provide commentary on the installation as a whole, putting conventional fine art prints in dialogue with the less formal medium of wooden blocks. Balance is abundantly apparent not only within the wood-block assemblage, but in the thoughtful and deliberate arrangement of the prints bordering the wall installation. The mediums work cohesively to deliver a ludic, thought-provoking, and intuitive experience for the viewer.

Holly Bostick Miller is a second-year MA candidate in Art History specializing in Ancient Art and Architecture. She is the President of UGA’s Association of Graduate Art Students and has both curatorial and archaeological field experience. Holly received her BA in Art History from Oglethorpe University in Atlanta in 2015. A study-abroad experience in Greece spurred her current interest in Ancient Greece, specifically the votive and funerary contexts of Greek banquet reliefs. Holly plans to pursue a PhD in Bronze Age Aegean Art and Archaeology after completing her MA in the spring 2020.

Alec Kaus

“Forgetting Everything But You” is a series of photographs created with my partner, in response to the 1,030 miles which newly separate us.

I have trouble making definitive statements; so, too, I have trouble making definitive photographs. As such, my imagery employs metaphor, abstraction and fragmentation to obfuscate the details of any one image, relying upon the combination of myriad details across images to piece together any greater sense of narrative or emotion. Though the work is born of my own personal situation — being separated from my partner — the facts of the story are not the point; it’s about the feeling, the emotion imparted upon the viewer.

My work is, but also isn’t, my life. It has always been motivated by deeply personal concerns, even if my goal is not necessarily to illustrate them. Creating photographs is a therapeutic act, a way to exert my control over a world which defies it. As such, I’m always working within little series, sentences or stanzas that, in their idiosyncrasies and surface-level incoherence, slowly and constantly pile atop one another, building toward something larger than the sum of its parts. Currently, in “Forgetting Everything But You,” this method plays out relative to immediate, personal dilemmas concerning complicated notions of love, place and transition.

Tightly cropped in black and white, deep furrows of rough-hewn shape give way to a dusting of earthy lichen. What would ordinarily be an innocuous detail of the landscape, “Trace” presents as an intimate exploration of a fragmented world. The crisp texture creates a palpable experience, but rather than recalling the environment with perfect clarity, the image evokes the rasp of bark against skin, the nostalgia of wind and heat and sweat. Alongside “Traces,” “Tenderness” creates a delicate balance of textures, coarse stubble giving way to smooth expanses of peach-tinged flesh. The contours of jaw, Adam’s apple, and collarbone seem to echo “Traces,” calling forth a wistfulness heightened by desire.

Collectively entitled “Forgetting Everything But You,” Alec Kaus’s photographs are deeply personal and intimate—chronicling his experience of being separated from his partner Harrison, who recently moved, while grappling with graduate school in a new state. These photographs have become mementos of their time—both together and apart. Rather than creating concrete narratives, Kaus instead focuses his lens on bodies, objects, and patterns—landscapes and portraits condensed into fragmented forms, their disparate details invoking emotion and tantalizing the senses. For both Alec and Harrison, their environment helps define their sense of place and home. The mountains of coastal Maine, the forests of rural Georgia, and the cactus-studded hills of Texas have become peripheral characters in “Forgetting”—alive, breathing, their expansive vistas enhanced by love, desire, mutual discovery, and memory.

Memory and absence play significantly into Kaus’s work, entwining the complex and transitory moments of Alec and Harrison’s lived experience together, and enhanced emotionally by their subsequent separation. Despite the circumstances of their initial capture, these images transcend any one moment in time and evolve, influenced by further experience—the longing and anticipation of being apart, or the joy and exhilaration of reunion. Kaus takes further influence from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “Observations on the Long Take,” in which Pasolini asserts that a long take, like life, is comprised of a series of disparate possibilities that find meaning and focus in death. Like the long take, “Forgetting” capitalizes on the failure of memory, as depicted details separate from their immediate context and become alive with renewed, poignant meaning in Alec and Harrison’s recollection. Rather than a lush forest, rough bark beneath fingertips recalls the warm and prickly sensation of stubble and skin, moments of intimate caress and inflamed desire interwoven with abstracted environments. But while these images exist as a product of Kaus and his partner’s time apart, the fragmentary nature of the photographs releases them from any one narrative, allowing viewers to explore and discover for themselves, and reconcile their own place and home.

Megan Neely

Leah Mazza

Horror films lure their audience in with shocking imagery and unsettling details. For example, when strong emotions are expressed physically, colors are striking, mark-making is fast or found in strange places and the walls become a canvas for rage. Similarly, in my work, weathered found objects are alchemized through drawing, color, texture, knotting and cutting. Residual energy is seen in fracture, and the viewer can begin to seek truth and awareness in spirituality, technology, capitalism and power. This body of work is about self-healing, reflection and finding clarity in the mysteries of our universe.

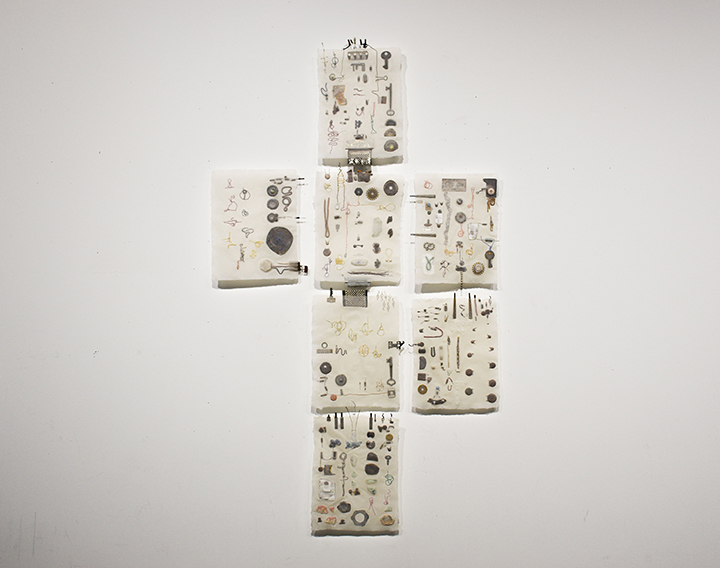

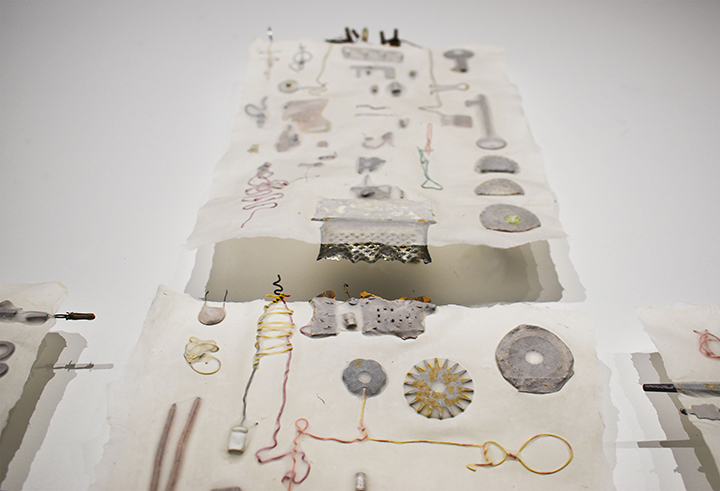

Leah Mazza’s interests connect her sculptures and two-dimensional pieces to the macabre mysticism of both Middle Ages and the popular horror-fueled film aesthetic of the 1990s. Her work takes inspiration from the human body and a kind of private symbolism, inspiring mystery rather than conclusion. She aims to challenge her viewers’ perception of reality through images that are reminiscent of tarot cards and dream symbols. Found objects form the foundation of her work, which is designed to pique interest and appeal to the subconscious. Otherwise innocuous and often discarded objects—industrial debris, bits of plastic, wood—are gathered and reconfigured by Mazza to create both geometric and organic forms—crosses and right angles but also curvilinear shapes akin to an animal’s innards. No piece has a singular universal “meaning” but instead is constructed to be transgressive of binaries and in a constant state of transformation and communication with the other pieces and with the viewer—much like a psychic reading a one’s tarot cards.

Mazza’s exhibited works pick at the differences and similarities between mechanical and biological forms such that her work might at one moment appear drawn from a nineteenth-century book of botanical samples, and at another moment, to align more closely with H. R. Giger’s grisly designs for the Ridley Scott film Alien. Each work of art seems to be a functional object rather than a merely aesthetic one, and viewers might find themselves wondering what each piece might do once the lights are turned off and the viewers all leave the gallery.

Mazza was trained as a draftswoman with a secondary education as a metalsmith while an undergraduate student in Pennsylvania, but she has experience with costuming, theatrical special effects, and paper crafts. As shown in her present work, she has combined this diverse array of technical skills into a whole that is both sculptural and two-dimensional, using many contrasting media. Her work is minutely detail-oriented and mystical, aiming to inspire close study and wonder.

Hannah Williams is a second-year candidate for a master’s degree in art history at the University of Georgia. She is from a small suburb outside Charlotte, NC, and she just recently defended her thesis on the effects medieval devotional practices on private Northern European religious art from the 15th century, specifically the effect of the “devotio moderna” on Hans Memling’s paintings.

Robby Toles

Images of the Amazon wildfires are shared on someone’s social media stories; they expire 24 hours later along with their sympathies. Following the 2016 election, smiling selfies are posted with shirts that read “Not My President.” After Mark Zuckerberg testifies against the Senate on data protection, memes about identity theft are rampant. Real issues with long-term effects are hollowed out by the individual’s preoccupation with the image of themselves as a concerned citizen. At the same time, phenomena that exist online influence the way individuals understand their relationship to themselves in the real world.

My work asks more questions than it can answer about this relationship; it does so via media that are themselves implicated in these issues: photography, video, computer-generated imagery and installation. Making matters more complex and partial is the fact that I frequently appear as a performed character within the work — one whose identity is intimately aligned with my image, but who often dangerously flirts with disassociation. Romantically swinging a selfie stick and artisanally crafting political posters for sale, this character lacks authentic convictions and is ultimately concerned with the power of the image. The blurred line between me and this character points to the lack of distinction between scrolling and sharing, online and offline, living and working, identity and image.

Referencing this confusion — and making it the subject of installation art — affirms cultural absurdities but also presents an opportunity for clarity. Screens, photographs and objects from the digital landscape demand a different kind of attention when in physical space, bringing the issue of our relationship with technology to the surface of our consciousness. By giving images material dimension, I question if they are merely our tools and ask if they might instead be the environment in which we live in and by which we are shaped. This confrontation creates a space for the individual to understand their position in a world that is made, literally, of images. More importantly, it exposes that distinctions between image, technology and individual are no longer separable.

Blanket Statement Grab Bag from Robby Toles on Vimeo.

Fort Da MFA installaion from Robby Toles on Vimeo.

Immortal Beloved from Robby Toles on Vimeo.

“We are all…hybrids of machine and organism…we are cyborgs.” So wrote Donna Haraway in her 1985 “Cyborg Manifesto.” Almost 40 years later, Haraway’s theory has become our reality, as individuals are intertwined with, and inseparable from, technologies. Our phones are AI appendages—bending to and controlling our desires and disseminating our images. Distinctions between the “real” and the “virtual” are increasingly difficult and fruitless to identify. Through photography, video, and computer-generated imagery, MFA candidate Robby Toles (de)constructs the “real” and the “virtual” in search of an intra-authenticity during this era of mediated reality. Toles’s subject matter and mediums are one in the same as he uses common social media platforms in his work to address the contentious themes of acceptance and alienation, often using his own image as his form and content.

Toles explores authenticity in an age of social media first through “Bob,” a computer-generated, realistic persona imbued with his own virtual/real life. An idealized avatar of Toles, “Bob” seems to be a certain design-savvy type replete with trendy social media accounts, cool friends, and a successful graphic design business. But the relationship between Toles and Bob is complex, and sometimes intertwined. While it seems as if virtual “Bob” makes posters that feature in Toles’s exhibited work “Blanket Statement Grab Bag,” in reality it is the artist himself. This multimedia work consists of a digital video, an over-sized, industrial white bag, and, inside it, hundreds of canvas posters with familiar yet vague political statements such as “Self Care” and “Hard Play Hard Work.” In the digital film, we see Robby, in an informational ad for the company, creating the posters, which then fall into the now-materialized grab bag; through the video, visitors are invited to take a poster whose sentiment suits them, before perhaps hanging them on their walls at the mantra of their new, or newly bolstered, identities.

By creating “Bob,” Toles distances himself from his work, and thus distances himself from his audience. An act of social distancing in an era of social distancing, Toles is there, but elusive, accessible only in mediated form. Toles’s “Fort Da!”, the title of which alludes to Freud’s discussion of a child’s game whereby a toddler masters the phenomena of distance and loss, borrows a format born of social media: namely the “boomerang” video, wherein a very short video is “looped” on repeat for 7-10 seconds. In “Fort Da!”, this format is complicated by the fact that two tracks are sutured together: the artist’s dog is filmed in boomerang style, but was then layered atop a narrative 10-minute video of a park; in the distance we hear other people and dogs in linear time, while Bowie is stuck in a loop. In “Immortal Beloved,” a 8:55 digital video of the artist reclining on a plaid picnic blanket with wine, a journal, and selfie-stick, set against a computer-generated backdrop of a grassy knoll and wood, Toles focuses again on the themes of distance and loss. The video oscillates between multiple views of the artist, as he records himself performing a lover’s soliloquy for the camera appended to his selfie-stick like a Shakespearean dramatist. As the film glitches and morphs as if inside the “web” of the internet, and Toles requests his followers to subscribe to his social media, we are left to ponder the nature of the artist’s (and by extension our) reality: simultaneously lived and acted, performed and imagined, embodied and virtual.

With the virtualization of the 2020 MFA exhibition due to COVID-19, Toles’s work may fulfill its teleological goal: presenting a mediated experience of a dualistic identity wherein the “real” and the “virtual” are compressed into one cybernetic organism. The loss, however, of the embodied presence of the viewer in the installations, for example how he originally intended for his viewers to recline on a gingham blanket to view “Immortal Beloved,” thus mirroring the artist’s posture in the film, removes the empathetic responses on which Toles’s oeuvre relies. As experienced through the compression of the artist and his virtual-self, “Bob” into one entity, there remains a human need for a self-realized identity, acceptance, and communion with others—one that cannot be replaced by a screen.

Jordan Dopp

Kim Truesdale

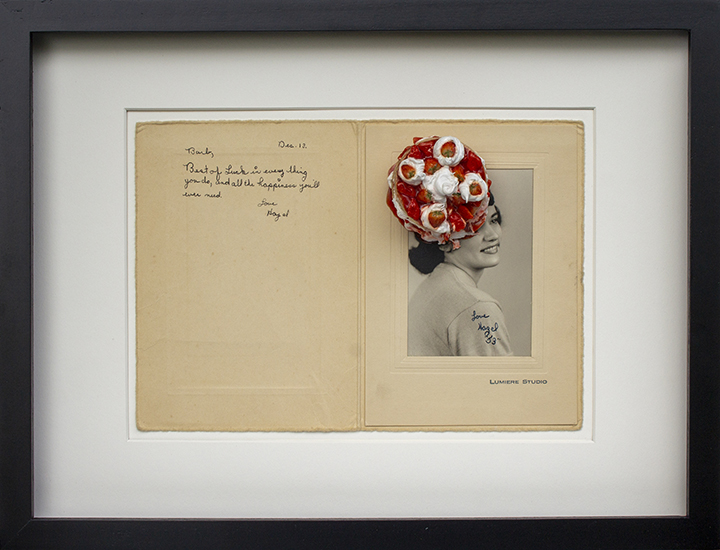

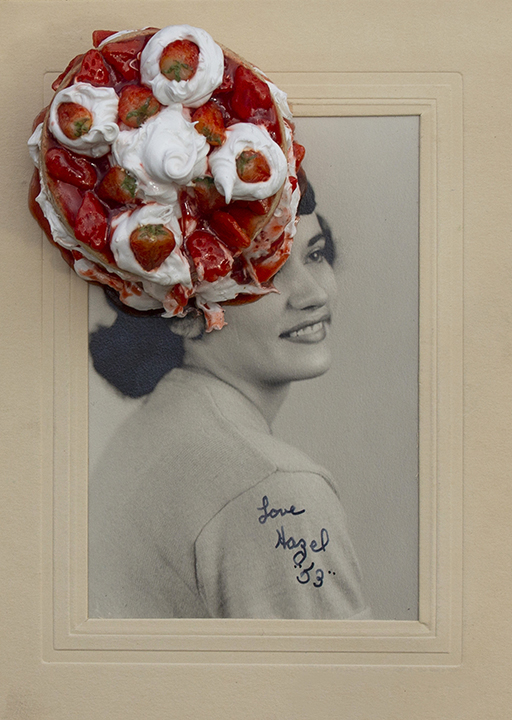

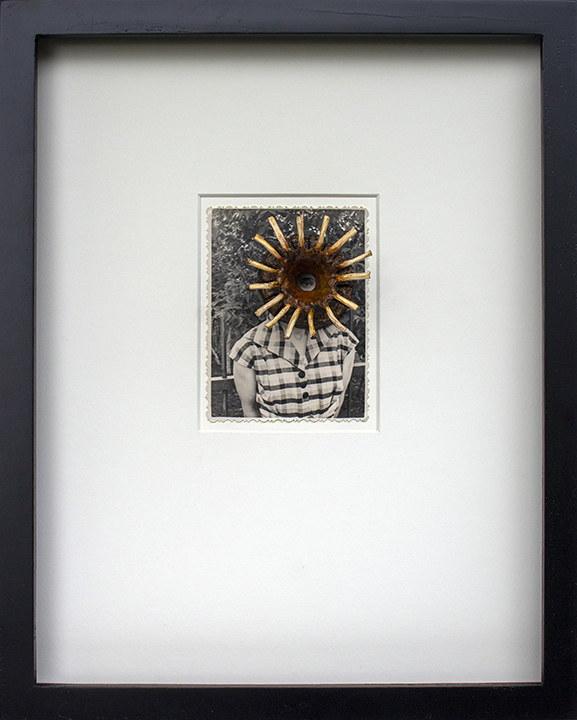

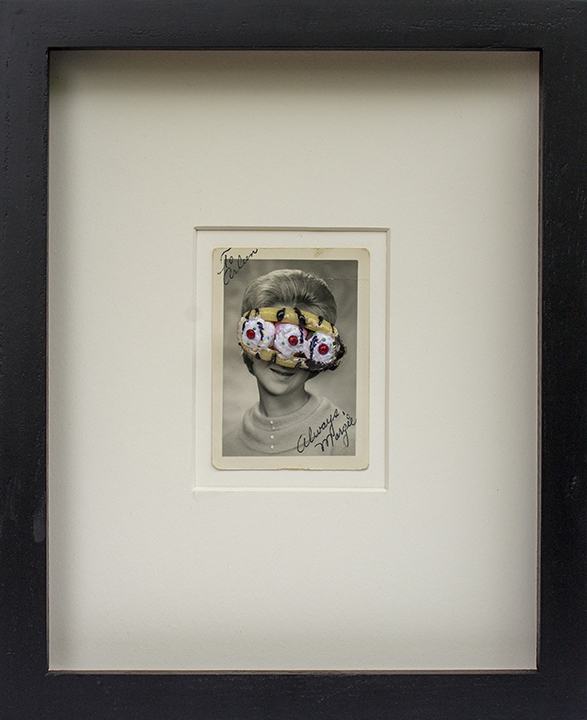

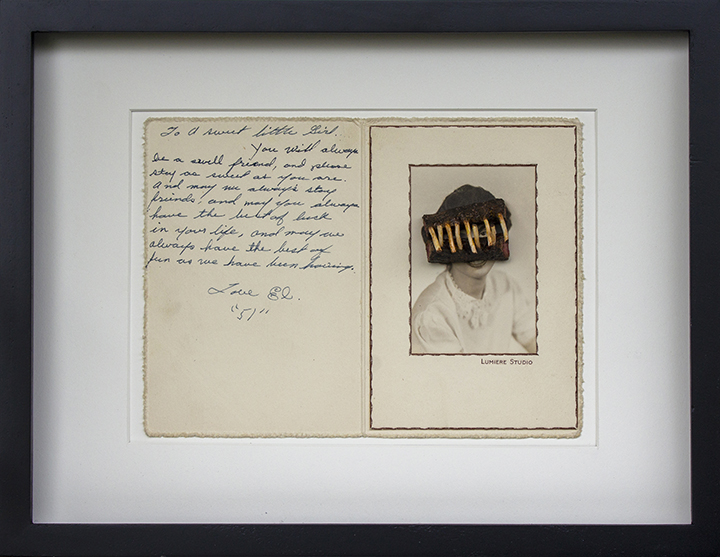

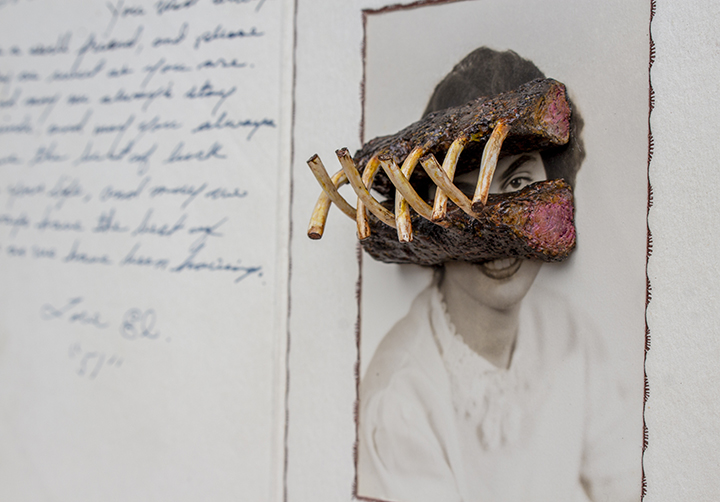

Observing how the conservative southern women in my family adhere to traditional gender roles prompted my investigation into the loss of women’s identities and individuality. After a loved one, who was a homemaker, was subjected to a tragic and mysterious case of neglect, leaving her in a diabetic coma for several days, I looked for physical, societal and psychological evidence. Thus, the portraits that emerged in my multimedia series “Did You Get Enough?” are from family scrapbooks, found photographs and a series of 1950s and 1960s Future Homemakers of America scrapbooks. The sensory organs of the “future homemakers” are suppressed as a means of expressing subjugation and sensory deprivation. The act of discovering portraits of women is important to my process as it is a way of preserving those who, like my family member, came to be overlooked or discarded.

Food functions in many complex ways in the lives of women. Untold stories and sugar-coated secrets consume women from the inside out. Over-eating can be a way to fill an emotional void, creating a false feeling of fullness or temporary wholeness. Or in a positive way, food can represent nurturance and love toward others. The miniature trompe l’oeil food sculptures in my work are based on memories from my mother and grandmother’s kitchen and nostalgic American cuisine. These food sculptures not only symbolize the familiar and staying in your comfort zone but also a societal or personal barrier that I hope these women choose to reject.

For artist Kim Truesdale, an old photograph speaks to more than personal memories. Finding interest in images of strangers, Truesdale combines them with portraits of her family members culled from scrapbooks. As such, Truesdale’s work speaks to the shared experiences of women, as well as her Southern roots and personal encounters.

After a tragic incident within her family, Truesdale became interested in how Southern women cater to the needs of others and follow traditional gender roles –often at the expense of their own identities. Creating sculptures of food made from palmer clay and decorated in various media including acrylic gel and pewter, Truesdale carefully combines two media—photography and sculpture—by adding her own handmade, three-dimensional works directly to the surface of the photographs’ glass frames to create a multimedia work. Truesdale positions these sculptures in powerful ways, using them to conceal facial features such as the eyes, mouth, or nose to symbolically represent how serving others can hinder one’s own faculties. Using foods from her memories of cooking in the kitchen with her mother, a talented baker, and her grandmother, Truesdale’s sculptures have personal meaning for her, even as they open up onto larger, historical concerns about women, domesticity, and food. Viewers will find that Truesdale’s food sculptures also mimic everyday accessories like hats or glasses, providing her work additionally with a playful touch.

Truesdale’s series “Did You Get Enough?,” which consists of images of Truesdale’s relatives as well as found photographs, makes reference to a question frequently asked at the end of a meal, often by female hostesses, to ensure that their guests have had enough to eat. As food can often serve as form of comfort, a means of indulgence, or as a way of bringing people together, Truesdale’s combination of food and faces can bring forth many meanings to viewers. Seen individually, unique details of each photograph are revealed. Some photographs in the installation employ original handwritten notes, or have paper borders trimmed in decorative patterns. Though some of these photographs may have been left behind by others, Truesdale highlights their sitters’ individuality and links their shared experiences; the foods become metaphors for burdens faced throughout their lives. All individually displayed in black frames and hung together on a wall as a unified group, Truesdale’s three-dimensional works from the series collectively show the breadth of women who were part of a shared phenomenon. However, despite these barriers, Truesdale hopes each of them rejects the weight placed upon them and retains the individuality evident in each of her portraits.

Catherine Ann Earley is a second-year MA candidate in art history at the University of Georgia. She graduated from Wofford College in Spartanburg, SC, in 2018 with a double major in art history and English literature. Earley studies 19th-century American art and her master’s thesis addresses the role of women artists’ studios in late-19th-century America in a series of photographs of American portraitist Cecilia Beaux.

Rachel Watson

Central State Hospital (1842 – 2010), like most mental institutions of its time, has a very dark past. My extensive research of this institution was primarily conducted at the Special Collections Library and the Georgia Archives, where I read handwritten notes, patient registrars, newspaper articles and a variety of booklets and schedules. This research has complicated my understanding of and relationship to the complex history of Central State Hospital, including the problematic past that lead to the rejection of the Open Door Policy of 1973.

In September of 1973, Dr. Gary Miller, head of the State Division of Mental Health, directed that the Open Door Policy would be implemented at Central State Hospital by October 1973. The Open Door Policy gave patients in the Freeman Building more freedom to move about if approved by doctors. They could come and go from the building and visit the neighboring town of Milledgeville if desired. The policy affected 247 patients at Central State Hospital. Political tensions between then -governor Jimmy Carter and Senator Culver Kidd brought the Open Door Policy into the limelight, creating open criticism between those who were either for or against the policy. Kidd was accused of using scare tactics and deliberately praying on the patients at Central State Hospital as well as riling up the citizens of Milledgeville to begin a petition to oppose the new policy. Carter is quoted as having said, “we look on mental patients as someone to be protected, cared for, cured and released, not kept there to support the economic structure of a community.”

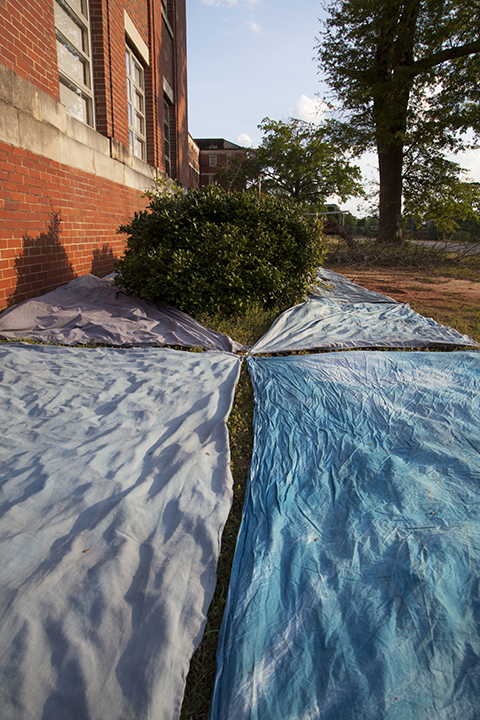

My work “247: Protected, Cared For, Cured and Released” is a symbolic response to the Open Door Policy and the patients that were effected by it. The 247 twin sheets create a cameraless photograph of the shadow of the Freeman Building, where the Open Door Policy was implemented. This body of work focuses on the forgotten, the neglected, the abandoned. It focuses on the people who were uprooted from their homes and admitted into a place with a horrifying reputation and the fear they must have felt. The buildings that they lived in, that they died in, that forever changed them are the subject of my recent multimedia exploration of a well-known, defunct mental institution in Milledgeville, Georgia.

All research for the Open Door Policy was completed at the Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies using Atlanta Constitution newspaper articles from 1973.

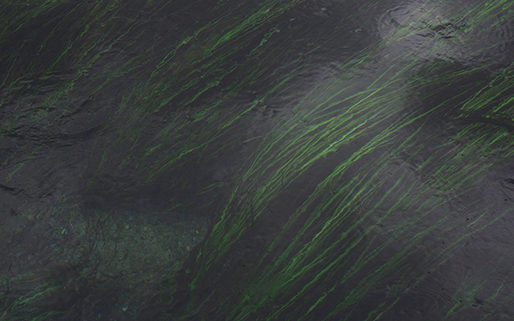

Rachel Watson’s installation of cyanotypes on bedsheets is a personal and symbolic response to the long and fraught history of the Central State Hospital in Milledgeville, Georgia. Entitled “247: Protected, Cared For, Cured and Released,” the installation derives from intensive research conducted at the Special Collections Library at the University of Georgia and the Georgia Archives. In particular, Watson’s work responds to the tension and effects of the Open Door Policy.

Written by the head of the State Division of Mental Health, Dr. Gary Miller with the intention that it be implemented during the fall of 1973, the Open Door policy would have allowed patients in the Freeman Building the freedom to roam the grounds of Central State Hospital as well as the town of Milledgeville, and it was conceived in an effort to reintroduce patients to society. 247 patients would have been affected by this policy, hence, the number of cyanotypes in Watson’s installation. However, political tensions between the then governor of Georgia, Jimmy Carter, and Senator Culver Kidd blocked the implementation of the policy. Kidd was accused of inciting fear among the residents of the surrounding area and began a petition opposing the Open Door policy. In statements against this petition, Carter is quoted as having said, “We look on mental patients as someone to be protected, cared for, cured, and released, not kept there to support the economic structure of a community.”

Watson’s work is comprised of 247 twin-bed flat sheets arranged in piles that are approximately 36” x 95” x 63,” imprinted with the shadow of the Freeman building at Central State Hospital. Cyanotyping is a camera-less printing process that results in cyan-blue images. The process typically uses two chemicals to achieve the desired print: ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. Purchased from thrift stores, Watson first laundered the bedsheets to remove any contaminant that could affect the cyanotyping process. She then soaked them in the appropriate chemical solution and dried them overnight in a space that eliminated contact with UV rays. Watson then laid the sheets in a grid, adjacent to the building where its shadow would fall upon them. Those laid outside of the shadow turned a dark blue, while sheets kept in the shadow are comparatively lighter. The intended final installation for the work is the 247 sheets stacked in front of the Freeman Building.

Watson’s cyanotypes are created by shadows. Shadows, in their very nature, are only representations of objects and never serve as the actual object they mimic. By creating works from the shadow of a building with a horrific history, Watson calls attention to the forgotten and neglected patients of Central State Hospital, along with the fear and horrible conditions to which they were subjected.

Ashlyn Davis