Museum education interns Emma Callicut and Angelica Millen (both students at the Lamar Dodd School of Art) put together this exhibition, which was on view as a pop-up in the museum’s Shannon and Peter Candler Collection Study Room on March 23, 2023. They selected all these works by women from the permanent collection and wrote the label text for each one.

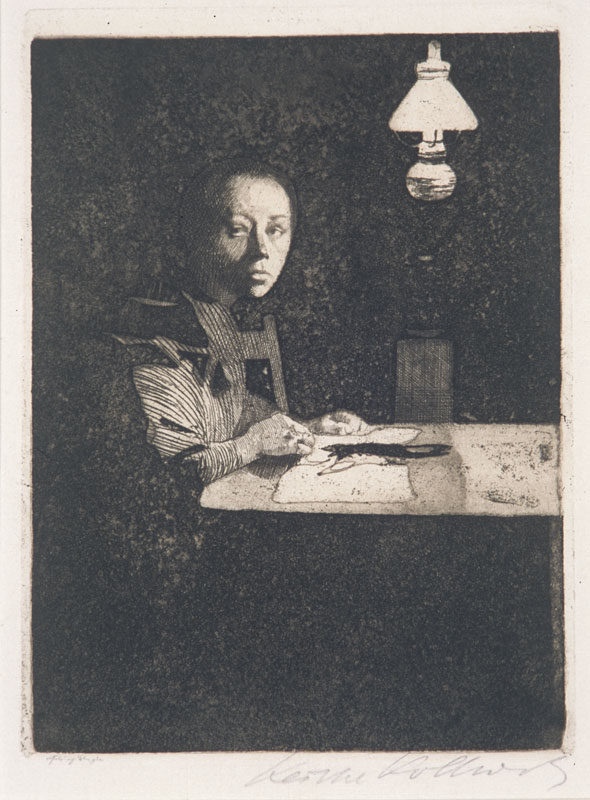

The printmaker Käthe Kollwitz grew up in a socialist household during an era of widespread industrialization. “March of the Weavers” is the fourth etching from her series “The Rise of the Weavers,” inspired by the play “The Weavers.” Detail within the faces of the marchers brings attention to the working class’s emotional state. Kollwitz was nominated for a gold medal in the Great Berlin Art Exhibition for this work, but she did not win because she was a woman.

Minna Citron made both realistic and abstract expressionist art, inspired by the avant-garde Jews who fled Europe during World War II. Citron was also Jewish and used traditional techniques to highlight her heritage. She often responded to place and origin in an abstract way. In “Urban Mystique,” she uses a printmaking process called photo etching. This technique dates from the early 19th century and produces photos on a metal plate. Citron’s image shows a shape that looks like a building and destruction surrounding it.

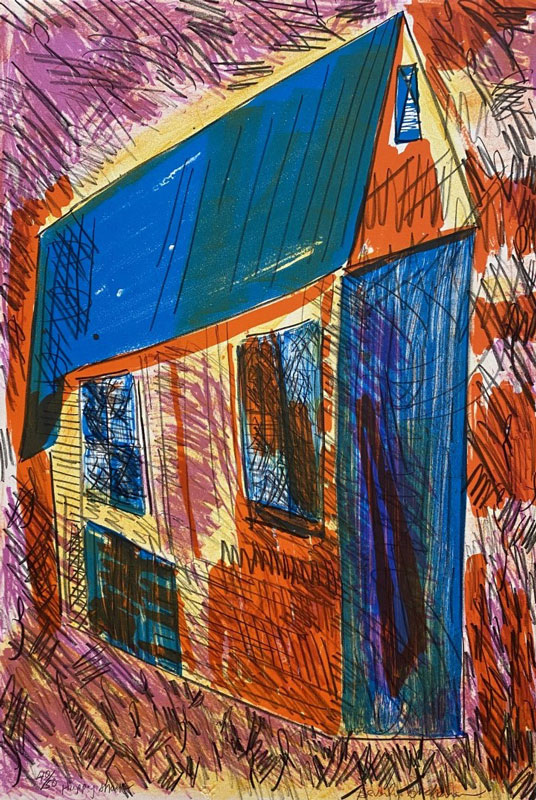

Beverly Buchanan was a Black artist who worked in a range of mediums, from sculptures to paintings. Much of her work relates to her upbringing in North Carolina. She was heavily influenced by rural southern architecture and landscape. “Happy Shack” is a collaboration with Wayne Kline, the leader of Rolling Stone Press, an Atlanta-based printmaking studio (not to be confused with the rock and roll band). Due to this collaboration, Buchanan was able to print in color for the first time.

Bessie Harvey sought to create art that relayed her perception of religion, nature and culture as a Black woman in the American South. She based her work on visions of human-like forms that she believed were messages from god. In “Stranger,” Harvey uses markers to create a tangled, gestural work that blurs the line between nature and the figure.

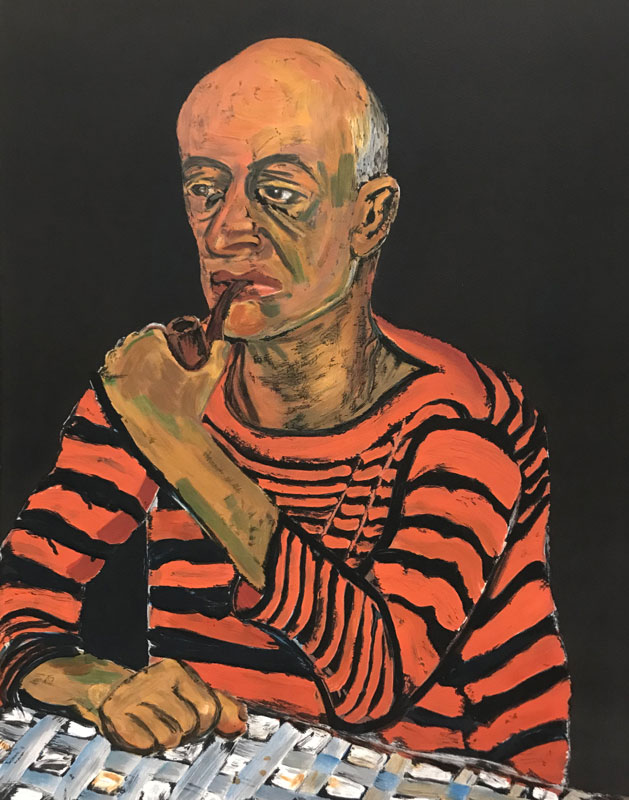

Alice Neel approached portraiture as a tool to capture the energy and spirit of her time. She described herself as “a collector of souls” and sought to reveal psychological truths within her subjects and their environments.

Margo Rosenbaum has photographed many artists and musicians. She was born in California, went to school in Iowa and worked in New York, but lives in Athens, Georgia. Her artistic practice and interest in music pairs well with the culture of Athens.

Pre-colonization, Native American people did not make prints. America Meredith claims the medium in “Stomp Dance,” using it to create a densely symbolic composition. Many Eastern American woodland tribes perform the stomp dance during the seasonal Green Corn Ceremony. The image shows a pair of legs wearing shackles, used as percussion instruments by women during the dance. Meredith uses contemporary means to highlight the role that women play in sustaining tradition.

“Wallowa Memory” pays homage to the Nez Perce inhabitants of northeast Oregon’s Wallowa Valley. The lithograph is a diptych (a work of art in two parts). The left side shows a design that Nez Perce women used on clothes and accessories to portray the idea of memory. The right side of the diptych is a realistic landscape. Kay WalkingStick is a member of the Cherokee nation and has Scottish-American ancestry. She uses this split work to express her biracial identity. To the artist and many Native Americans, the landscape is spiritual. She uses her work to connect people of all cultures back to the land.

Having grown up Black with Native American heritage, Thelma Johnson Streat focused on diversifying the modern art scene. She painted “Girl with Bird” later in her career while she was co-founding the Children’s City of Hawaii and New School of Expression at Punaluu, Oahu. The school encouraged multiculturalism and social acceptance through art-making. Inspired, Streat began incorporating the island’s children into her own artistic practice. “Girl with Bird” relays Streat’s lifetime of stylistic influences, challenges the conventions of portraiture and reflects the school’s ideology.

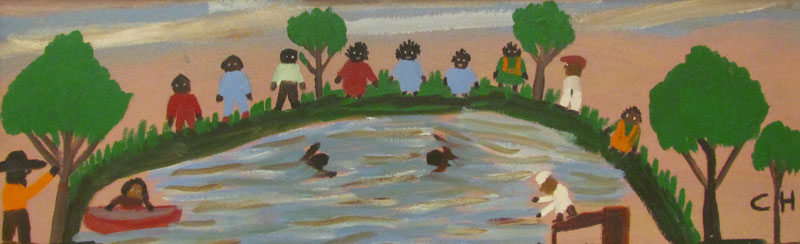

Clementine Hunter never traveled 100 miles beyond the Melrose Cotton Plantation in Louisiana where she was born. She was a self-taught artist who did not start her painting career until she was already a grandmother. The unique style she developed portrays memories and stories of southern Black American plantation life. Hunter is well known as an artist who painted purely because she loved to.

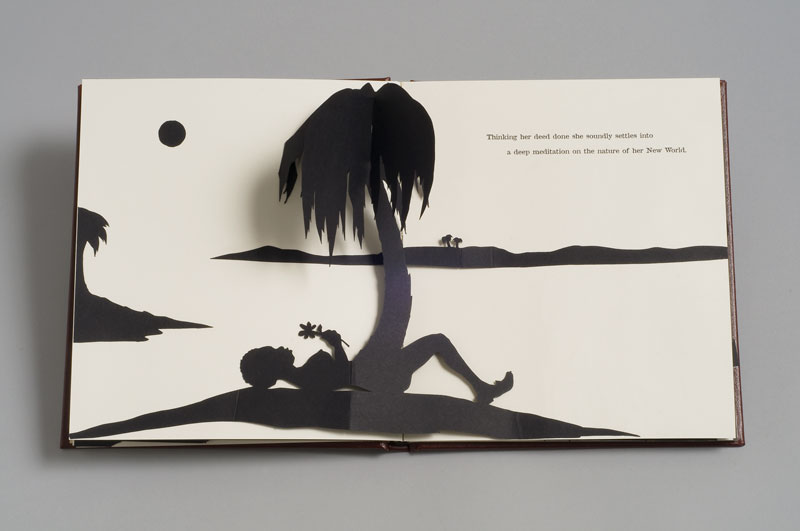

Kara Walker is known for her silhouette images. Her work addresses Black history in the Antebellum South. She constructs a parody of historically racist narratives about primitive Africa, Black beasts and Black women. At first glance, this story appears to be an endearing children’s book. But Walker uses the Victorian silhouette forms to tell a darker story of graphic violence, sex, racism and power dynamics.

The narrative of the pop-up book follows the story of a young woman named N who was freed after the Civil War. N dreams about going back to Africa, but instead finds herself on a ship with passengers who consider throwing her overboard or eating her. The reader may begin to question if freedom is just a fable for N.

As a woman and an artist, Elaine de Kooning broke many rules. She was an outspoken artist and art critic. This study is part of her “Bacchus” series, inspired by a 19th-century statue of the Roman god that she saw in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. De Kooning made more than 40 drawings and watercolors and 60 paintings in the series from 1976 to 1983.

You can see an example of one of the larger paintings in the series, “Bacchus #81,” on view in our permanent collection.

Jeannette Alexander Judson studied and worked in New York City. She was a member of the National Association of Women Artists, the first women’s fine art organization in the country. Women artists were excluded from art salons, galleries, and exhibitions during the 19th century. The women who founded NAWA in 1889 and continue to create spaces for women in art today.