Beyond Utility: Rugs of Southwest Persia

Iran and the surrounding area sustain a very rich cultural and demographic diversity. Tribes of peoples historically speaking a variety of languages and moving nomadically through that ancient-settled space generated numerous artistic design traditions in weaving. At the time of these rugs’ creation, the area subject to our interest is that of southwest Persia, the earlier name for Iran. That weaving itself would be a paramount artistic technique is a natural outgrowth of herding peoples whose animals and their fleece were intimately tied to the grazing ecology, economic survival, and artistic production.

The rugs in this online exhibition tell a complex story of the way these peoples were able to capture the minds and markets of the world for their designs. Most often, these rugs are bolder and display a somewhat less refined design than the glorious formal urban rugs of the large cities of old Persia. That quality is not a shortcoming in these designs. The strong geometry and explosion of color within these rugs create a forceful artistic impact that is unlike the serene qualities of their counterparts whose superb compositions and execution bespeak centuries of palatial aesthetic.

Rather than seeking perfection, the makers of tribal rugs often seemed to hold a view of rustic weaving as fresh and homemade. The idea of the “Persian flaw” underlines these weavers’ aesthetic notions. This deliberately introduced weaving mistake demonstrates that only the creations of God are perfect. The concept also underlines that these workmanlike and productive designs were part of daily life and underscores the individual artistic freedom that tribal weavers enjoyed.

The Georgia Museum of Art thanks our guest curator, James Verbrugge, for sharing his insights, collection, and network of rug specialists. Online exhibitions have been in part necessitated by the circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic, and we began developing this one during the shutdown, while our galleries were closed. Given the limited space and reach of gallery exhibitions, online exhibitions also present an effective way of tapping the connoisseurship of collectors and specialists. Most objects are not in museums or public facilities but within the homes and collections of private individuals who develop excellent connoisseurship that should be given voice. James Verbrugge has served as a guest curator for us before, on “Rugs of the Caucasus” (2014). He is a noted collector and authority on rugs.

James joins me and the Georgia Museum of Art’s director, Dr. William Underwood Eiland, in thanking the Material Culture and Arts Foundation (MCAF) for their sponsorship of this exhibition. Their support covered the expensive photography as well as all other museum costs in sharing this beautiful collection of tribal Persian rugs. We are grateful for MCAF’s continued support of decorative arts initiatives.

Dale L. Couch, Curator of Decorative Arts, Georgia Museum of Art

Objects Tell Stories

Rugs from southwest Persia (Iran) are a distinct and important subcategory of Persian rugs. Until 1935, the region/country we now call Iran was known as Persia. In 1935, Reza Shah requested that Western diplomats use Iran as the official country designation rather than Persia. Iran is now in general use as the official geopolitical country name, but Persia continues to be used in historical or cultural contexts. We use Persia in this online exhibition and essay because these rugs date from the 19th century.

Often, people classify Persian rugs by the city or surrounding area where they were woven (for example, Kashan, Qum, Nain, Bidjar, Heriz). Rugs woven in the broadly defined area known as southwest Persia, however, are usually called tribal rugs and tend to be identified by the tribe or sub-tribe who wove the rugs (for example, Qashqai, Khamseh, Afshar). These rugs tell us something about the area in which they were woven, how the people lived who produced them, and the culture of the area. In short, these examples of tribal textiles tell us stories.

This exhibition focuses on rugs from four groups in southwest Persia: the Qashqai (probably the most well known), the Lurs, the Khamseh and the Afshar. Until the early part of the 20th century, these groups were mostly nomadic. They lived in tents and moved their tents along with their herds of sheep from summer pastures to winter pastures and back again. A limited number of tribe members might live in small villages. The women of the tribe used wool from the sheep or goats in their herd and looms that were easily carried with them as they moved. They made dye from a variety of insects and plants.

Rug patterns or designs are often associated with a specific tribe or sub-tribe, but it is highly unlikely there would be two identical rugs. Even those that might appear to be exactly alike will have some modest or slight variation in the border, field or colors. The weaver may insert a unique feature, either because she chooses to do so or as the result of inattention. In sharp contrast, Persian rugs woven in city workshops had patterns and designs predetermined by a “cartoon” (a grid on paper with cells colored to guide the weaver in selecting yarns to execute the design). These weavers were hired employees, and did not design the rug patterns. Rugs from these workshops were and are made for purely commercial markets, usually export.

The Tribes and the Confederacies

At first, the tribes in southwest Persia were organized as independent groups. Beginning in the 16th century, some of them combined into political structures known as confederacies, often to offset the influences of other tribes. Confederacies might but did not always share a common heritage. They did consider themselves distinct from other tribes or groups of tribes.

The Qashqai Confederacy was formed in the 16th century, although some of the tribes may have located in the region as early as the 11th century. Tribes and sub-tribes of the Qashqai include the Shekarlu, the Kashkuli and the Amaleh. Qashqai Shekarlu weavings receive special attention in this exhibition for several reasons: the fact that the sub-tribe no longer existed after the late 19th century and the fact that weavings from this group have a unique feature.

The Qashqai was the largest and most powerful confederacy in southwest Persia. Its member tribes were situated near the eastern shore of the Persian Gulf, in the Fars Province, with Shiraz as the capital. Some of its rugs were woven in small towns and villages, the “cottage industry,” but nomadic weavers who lived in tents and migrated seasonally made most of them.

The Lurs tribe was in southwest Persia in the Zagros Mountains, near the Qashqai. While several tribes were members of the broadly defined Lurs designation, they did not form a confederacy.

The Khamseh (Arabic for quintet or group of five) Confederacy was also in southwest Persia, to the southeast of the Qashqai. It was formed in the 1860s, primarily to counter the influence of the Qashqai. Tribes of the Khamseh Confederacy included the Arab, the Baseri and the Baharlu.

The Afshar tribe was to the east of the Khamseh, near the city of Kerman. This proximity means that some Afshar weavings exhibit the urban influence of Kerman, which continues to serve as an important weaving center of city workshop rugs. The original group of Afshars moved to this area in the 16th century. They were less nomadic than some of the tribes in the Qashqai and Khamseh confederacies. The Afshars were the smallest of the four tribes considered in this exhibition, and they produced both village and nomadic weavings.

The Rugs in the Exhibition

This exhibition includes 10 Qashqai rugs. Not only was the Qashqai Confederacy the largest and most powerful of the various confederacies and tribes, but it also produced the greatest variety of rugs, considered to be the highest quality rugs from southwest Persia. The Lurs tribe is represented by one rug that bears a remarkable similarity to a specific type of Qashqai rug. The Khamseh tribes are represented by one rug that features a field design more widely woven by the Khamseh than by other tribes. The final four rugs are Afshar weavings, two of which contain motifs that suggest an urban weaving influence.

The Qashqai rugs contain an abundance of motifs and symbols within the field designs: animal figures, birds and bird head figures, stylized tree forms and branches, swastika derivatives, rosettes and flower heads, flaming palmettes, checkerboard forms and human figures as well as other elements.

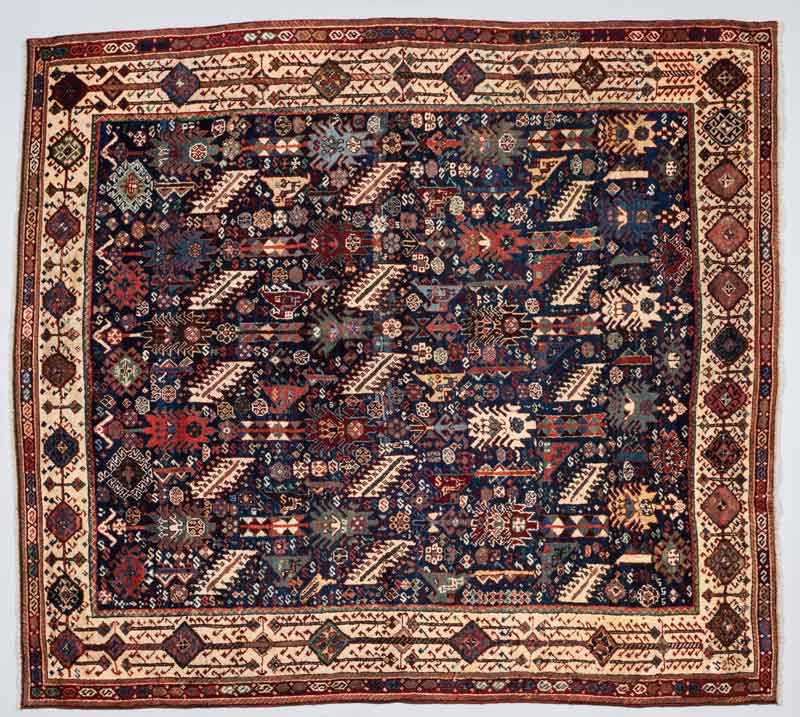

The first three rugs here were woven by the Shekarlu, a sub-tribe of the Qashqai that began to fade away in the early 19th century. By the end of that century, its members had been absorbed into other tribes in the region. As a result, rugs from that sub-group are exceptionally rare. Some Shekarlu rugs date from the 18th century, but the rugs presented here date from the mid-to-late 19th century.

Each of these three rugs has a wide white-ground border consisting of a series of medallions, some diamond-shaped and others hexagonal. Despite slight differences in the shapes of the medallions and the placement of the “bird heads” on the medallions, they are clearly identifiable as having a common origin. The border is one of the most important indicators of a Shekarlu weaving.

Their field designs, however, are very different. The first two in the group have what is known as the “ashkali” design, a series of geometric figures, each of which is unique. The white diagonal motif that appears to have the shape of a comb almost leaps from the photo. There are four combs in the first rug and 15 in the second. This symbol represents cleanliness, a very important quality in Islam, especially within the context of the prayers (salat) that are required five times each day.

This rug has a dynamic, multicolored field. Only a few of the medallions scattered around the rug have the exact same combination of colors and shapes. The field also contains two images of peacocks, one on either side of the rug near the middle. Slightly below them, we see three horned animals. Below those animals are three stylized tree forms. In the narrow borders on either side of the wide white border are S-shaped forms inside small medallions. The S form is an ancient symbol whose origin may be tied back to images of two-horned dragons.

The second rug has a dominant blue field highlighted by 15 comb designs. Indeed they stand out even more sharply than in the first rug. The other geometric shapes in the field are less orderly than in the ashkali design of the first. The field includes bird head medallions and palmettes. Tiny horned animals are almost hidden in some of the larger triangular forms in the field, and S forms are randomly placed against the blue background. This rug was featured and discussed in the article “Shekarlu Qashqai rugs” in the international textile journal Hali, issue #172 (2012), on page 33.

The third Shekarlu rug also has the white border, but its field design is very different and elegant in its simplicity. The repeating series of narrow stripes is known as the “moharamat cane” design. Within each stripe or cane is a series of meandering patterns and colors that add to the uniqueness of the piece. The cane design is likely to be from the Khamseh tribe.

This rug resembles a Qashqai Shekarlu rug because of its border, but is actually a Luri weaving from the Lurs tribe. The Lurs were in the Fars Province, very close to the Qashqai. This rug is an example of how designs sometimes traveled between tribes. It is also a long rug, which is rare in a southwest Persian piled weaving.

The field design bears some similarity to the border. It features a series of five stepped-diamond-shaped medallions, connected linearly with an anchor on each end. A variety of small diamond medallions and small octagonal medallions are set against the dark background of the field as are two colorful stylized bird figures.

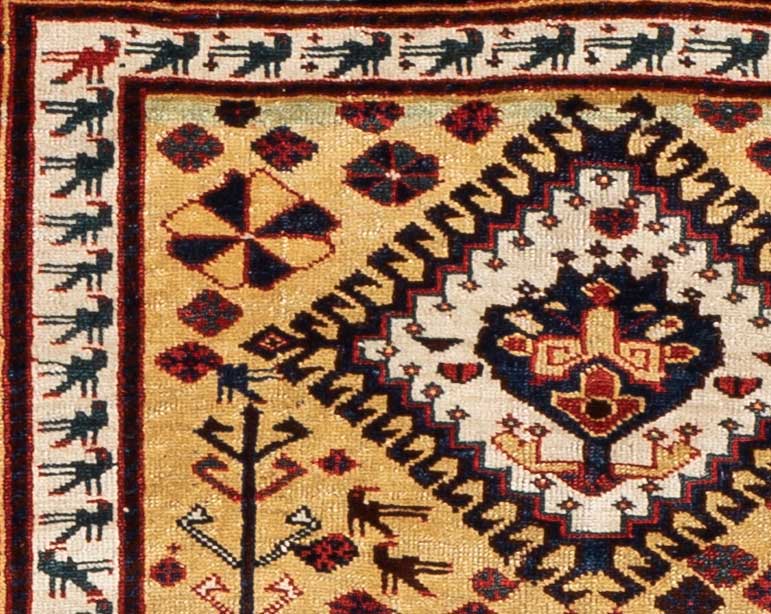

This rug is one of the finest examples of Qashqai weavings. It has two large bird head medallions, one at either end of the rug. The single most distinctive feature of this rug is the central “rug-in-a-rug” design. The inner rug contains three smaller bird head medallions in the center set against a yellow field that has several stylized trees and a variety of animal motifs and assorted small medallion-like elements. If you look closely at the very orderly inner border consisting of a series of green birds, you can see red birds, too. A single green bird points in the opposite direction of the others.

The “rug in a rug” is surrounded by a dark field that features a series of palmettes, two yellow lions, one white lion, and one camel. Given the complexity of the rug and the exceptional quality of the weaving, it may have been a commissioned piece or a dowry rug.

James Opie, author of “Tribal Rugs: A Complete Guide to Nomadic and Village Carpets” (the authoritative book on tribal rugs), suggests that this rug was woven by a master weaver who combined symmetry and improvisation. The four white spandrels provide symmetry, but within each one are elements of improvisation and freedom. Opie also emphasizes the lion motifs and the subtlety of the border of the inner rug.

This rug is a boldly colored Qashqai piece. It has a red field countered by a dark blue center diamond medallion with an inner hexagonal medallion featuring a series of branches extending from the center. The white inner border around the edge of the rug features a series of small rosettes. Other bold designs and colors include the four arms extending from the blue medallion that culminate in four rectangular hooked forms, almost like a checkerboard pattern. The rug’s most outstanding feature is its four lion motifs, two white and two bronze. There are peacocks near one side of the rug and several horned animals and horizontal S figures near the other.

Some early rugs from the Lurs and Qashqai who resided in the Fars Province were known as lion rugs, with the entire field of the rug comprising a single large lion figure. This later example carries on the tradition in a more subtle fashion.

This rug, along with the one immediately preceding it, represents the epitome of very fine weaving from the Qashqai. One barely notices the series of narrow borders, with the exception of the white border with a distinctive meandering motif. The rug’s distinguishing feature is the series of 36 white palmettes that seem to jump out of the rug.

At first glance, they resemble menorahs, but they are more accurately called “flaming palmettes.” Zorastrianism, a religion that pre-dates the beginning of Islam in the 6th century, has fire as one of its major symbols. Founded by the prophet Zarathusta (known as Zoroaster outside of Iran), it is one of the oldest continuously practiced religions in the world. The rug appears to pay homage to this religion. Other distinctive characteristics of this rug include horned animal motifs, bird forms, the horizontal S form, tiny botehs (paisley motifs), and small medallions and rosettes.

This rug appears to be a very simple design but upon closer inspection is subtly complex. The field pattern in this rug is usually woven as a kilim flat-weave rather than the wool-piled weaving style of this rug. Rather than having an identifiable center, it has an all-over design of 18 squares, most of which are orange/red but two of which are blue and one blue/black. Five of them are striking and unusual examples of negative space, with nothing to break up the striking background color. The other 13 each have a tiny, almost hexagonal medallion in the middle, no two of which are exactly alike.

Another interesting feature of the rug are the stripes that separate the squares. Closer inspection reveals that some of the tiny geometric shapes set in the white background are swastikas. This motif has been used in rug weaving in a number of cultures over the years, including rugs from the Caucasus and from Navajo tribes in the southwestern United States. It is an ancient symbol of prosperity and good fortune. The word is derived from the Sanskrit “svastaka,” meaning conducive to wellbeing. In addition to the use of the swastika symbol in rug weaving, it was widely used in a number of religions long before it became associated with the German Nazi Party in the 1930s.

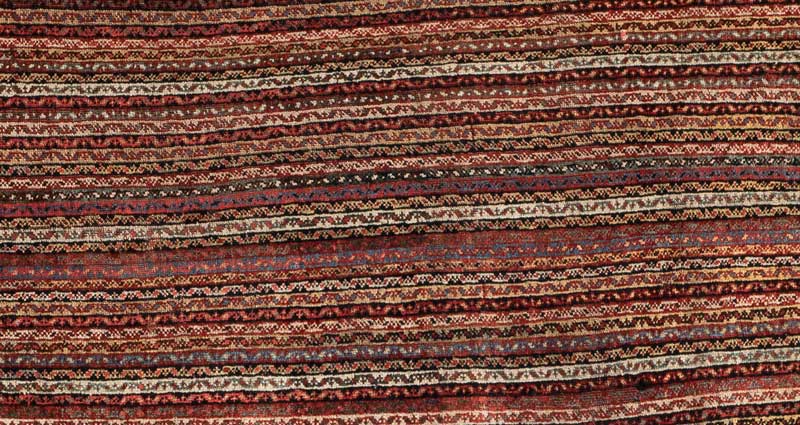

The next two rugs are distinctly different from any of the others in this exhibition. They show how textiles from this region were used in day-to-day life by the nomadic tribes who made them. They were functional as well as decorative. The first (above) is an exceptionally colorful striped kilim weaving (flatweave). Most of the stripes contain a variety of geometric shapes, some with zig-zag patterns. Each series of patterned stripes is followed by a narrow stripe virtually empty of any design.

These long and narrow kilims were not woven for floor coverings but to cover piles of sacks that stored grain or to cover other woven pieces (known as mafrashes) that stored clothing, bedding, and other household items. The kilims provided color within what were known as “the black tents” of the nomadic tribes. Given the high quality of this example, it may have been woven for someone highly ranked in the tribal system.

This rug is another weaving that is both highly decorative and functional. It is a flatweave known as a sofreh or eating cloth. It would be laid out on the floor on top of a rug that was the floor covering. Food would be then spread out on the cloth for a family meal. This sofreh is highly decorative. Its vivid field consists of a series of zigzag stripes broken up by a small diamond-shaped center medallion made up of nine smaller diamond medallions. The center medallion is duplicated in the four spandrels. The white border also features a series of triangular medallions, each of which also contains a small center medallion.

This large rug includes features that are seen in many Qashqai weavings but seldom all in one rug. Its multicolored field is dominated by three large white medallions, connected by a wide stripe with anchor-shaped designs on both ends. The large medallions stand out sharply in what is certainly a free form, or even random, format. Each medallion features a floral motif set against the white background filled with tiny diamonds, some of which are connected and some of which stand alone. The field itself is filled with almost every type of motif used in Qashqai weavings: stylized trees, small medallions of various shapes, palmettes, horned animals, peacocks and rosettes.

The orange/red spandrels, each of which contains a floral motif along with other tiny medallions, provide symmetry, as do the triangular indents on the sides. The series of minor borders are identical, whether highly structured or meandering. Overall, this is a truly exceptional example of Qashqai weaving in a relatively large floor rug. Its size provides the weaver with sufficient space to allow her imagination to flow freely. This rug was certainly not woven from a precise predetermined pattern.

This rug is an example of weaving from the Khamseh Confederacy. It features the moharamat cane design in the field. One’s eye is immediately drawn to the vivid blue medallion in the center, which is connected to two small diamond-shaped medallions. These medallions contain a variety of small motifs that at first glance appear to be randomly placed. A closer look reveals symmetry, especially in the center medallion.

The cane design was widely used in Khamseh weavings but not always with a center medallion. In this rug, each cane contains a series of meandering designs that create a feeling of movement. Each of the white canes is separated from the next one by two colored canes. One very subtle characteristic of the rug is the placement of the pattern in the cane immediately adjacent to the white cane. On one side of the rug, the meandering design is on the right side of the cane, and on the other side of the rug, it is placed on the left side of the white cane.

Recall the Qashqai Shekarlu rug in this exhibition in which the entire field consists of colorful canes (see detail above). The fact that the cane design is used in two rugs, each from a different tribe, is evidence of the fact that designs traveled.

Our final group of objects features four rugs from the Afshar tribe. This tribe lived to the east of both the Khamseh and Qashqai tribes, relatively close to the city of Kerman, which had rug workshops. Some Afshars settled in small villages near Kerman while others were nomadic. As a result, some Afshar rug designs reflect the urban influence of the Kerman weaving culture.

This Afshar rug features a tulip design, with a series of white lattices that cross the field diagonally. Within the lattices are diamond-shaped “tulips,” each of which seems to originate from a center medallion. The bright blue field is made even more prominent by the white border containing red human-like figures. They appear to march in an orderly fashion around the edge of the rug, carrying shields. Despite its age, the rug has retained its small flatweave ends.

This Afshar rug has a field known as the “chicken” design or “morgin” format. The field portrays a series of chicken-like motifs, separated by circular medallions. Inside each “chicken” is a small animal-like figure. To some observers, the figures resemble dinosaurs. To another, they might seem to simply be an undefined animal form. However it may be interpreted, the motif adds a distinctive feature to the design. Two of the borders are identical and illustrate what is known as the crab design. Between them is another border consisting of a variety of small medallions. A series of larger diamond medallions appears at each end of the rug but not on the sides, another distinctive feature.

The other two Afshar rugs are white-field Afshars. We include these rugs as a pair for several reasons. First, we know these rugs have never been separated. They were woven as a pair, either by the same weaver who wanted to tell a pictorial story with them or by two weavers, perhaps on side-by-side looms. They have traveled the world together. Second, each rug presents classic field designs set against a white field. The first rug has the well-known vase design. Two large vases are shown both above and below a center 12-sided medallion. Each of the four spandrels also contains a vase design with stylized branches. These motifs also appeared in Kerman city weavings.

The second white-field rug also includes a famous Afshar floral design, sometimes known as the “foreign flower” design. A variety of smaller floral motifs appear throughout the rug, both above the spandrels and at the sides of the rug. What distinguishes it from its vase-design sister rug is the four birds perched on top of the large floral emblems. Did the weaver do this to add a distinctive tribal feature to the otherwise traditional floral format?

White-field rugs as a genre are unusual. They are often referred to as wedding rugs, or sometimes dowry rugs. They may have been woven for a wedding, perhaps by the woman who was to be married, or used in the wedding itself. They represent another use or function of a tribal rug in addition to being a beautiful work of textile art.

In conclusion, this exhibition presents some outstanding examples of the beauty of 19th-century southwest Persian tribal rugs. High-quality rugs from this time period and region are exceptionally difficult to find, especially without the expertise and connections of a reputable dealer. Although this exhibition has focused on the weavings of only four tribes, others in the region also wove rugs during this period: the Bahktiari, the Shahsavan, and the Kurds. Many, if not most, of the tribes discussed here became less nomadic during the early 20th century and, as a result, much of the weaving culture of those earlier centuries is lost.