This is the online version of a pop-up one-night-only exhibition of spooky, scary and supernatural works from the collection selected by the museum’s education interns: Catie Cook and Andrew East. It was on display at the museum October 13, 2022, from 5 to 9 p.m.

This special pop-up exhibition is an assortment of spooky works from the museum’s collection.

The scary subjects of these works of art — ghosts, jackals, spiders and more — are familiar icons of Halloween that we revisit each October.

What gives you a scare?

The moon will shine for God

knows how long.

As if it still matters. As if someoneis trying to recall a dream.

Believe the brain is a cage of light

& rage. When it shuts off,Something else switches on.

There’s no better reason than now

to lock the doors, the windows.— Burlee Vang

from “To Live in the Zombie Apocalypse”

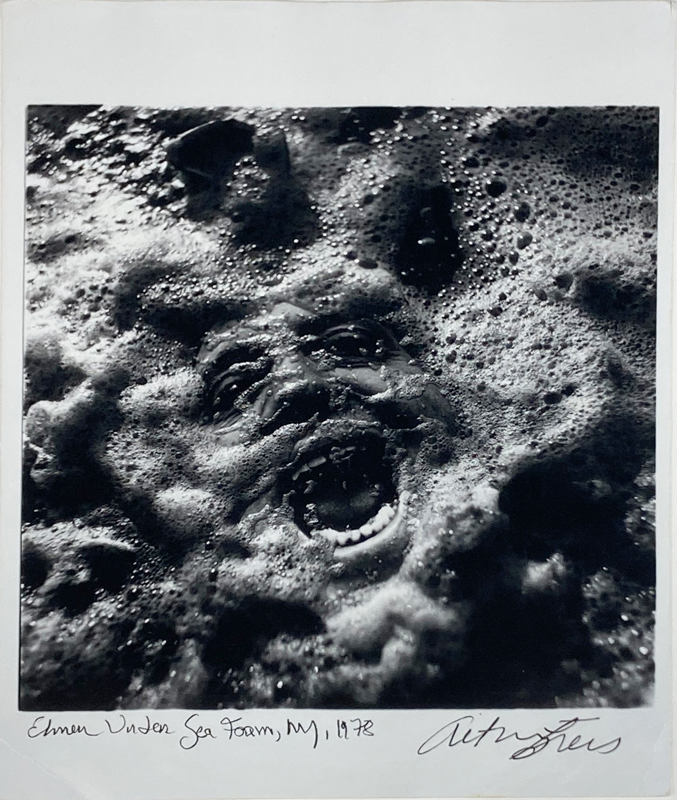

This photograph is part of a series featuring Elmer Klein, a poet, playwright and mentor to Tress. They collaborated on the book “Elmer Over Time,” which balances documentary photography with manipulated storytelling. The photography reflects the inner workings of the artist’s imagination and blurs real horrors with imagined horrors. Here, seafoam engulfs Elmer’s face. There is horror in both the act of drowning and the facial distortion created by the water. Rather than being sucked under the dark tide, Elmer seems to morph into the foam, entrapped.

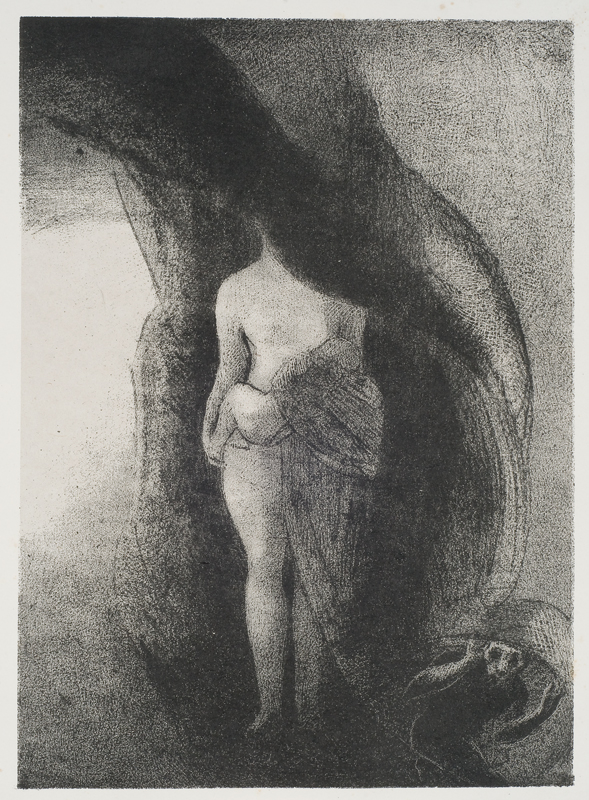

Carrière’s print comes from “L’Estampe Originale,” a periodical that united the most influential printmakers of late-19th-century Paris. It also helped to foster technological developments in the art of printmaking. The title, meaning “the original print,” supports the argument that printmaking is a legitimate and innovative discipline. Carrière’s lithograph process instills a ghostly quality in this image. The figure is a fleeting mystery as she dissipates into the background. Is the head materializing before your eyes or dematerializing into the mist?

Baskin described himself as “crow-haunted.” This woodcut includes nine crows, perched beside a block of Hebrew text and human skulls. What defines his artwork is a purposeful interplay between visuals and text that showcases his Orthodox Jewish upbringing. However, Baskin was not concerned with nobility but rather what “survives in the afterglow of collapsed religion.” The crow reappears as a remnant of this collapse, embodying wisdom and predation. Although a pioneer in printmaking, he preferred sculpture, his most famous being the Holocaust Memorial in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

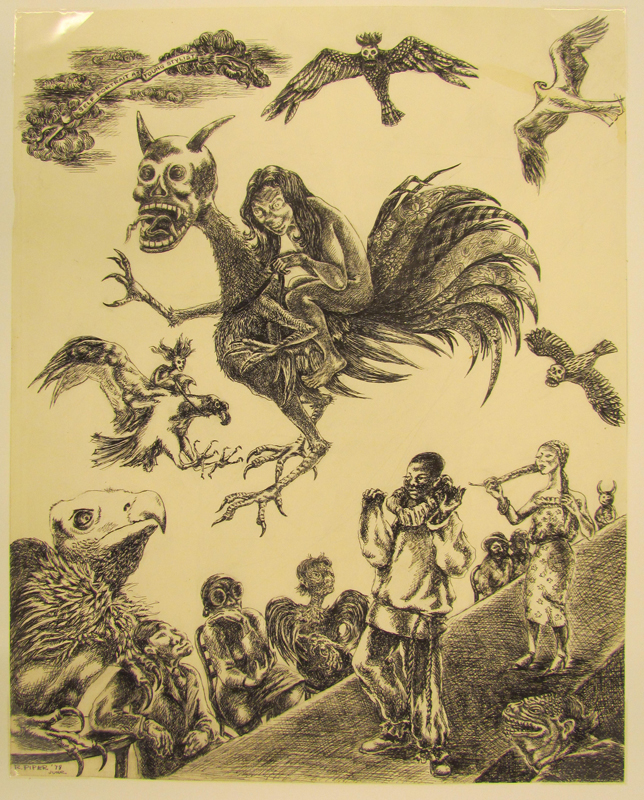

Perhaps her most fearsome work, Piper created “Self Portrait as a Young Stylist” following a 28-year hiatus from fine art. Ghoulish birds soar into view, intermixed with skulls. She pictures herself in clown-like attire, walking a runway before an audience of anthropomorphs. The image involves spectatorship and is highly narrated — it is hardly self-portraiture. Piper immersed herself in the blues music scene, elements of which appear in her figuration. Yet, she feared being stereotyped as a Black artist and chose to adopt styles from the medieval, such as the Flemish School. The banner in the clouds might suggest a southern Day of Judgment.

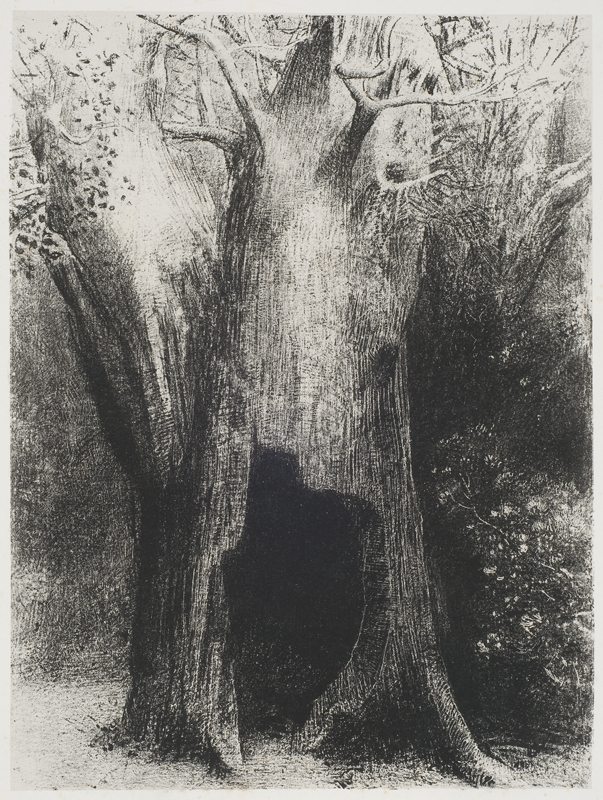

Saint Anthony sees a forest in this illustration for Gustave Flaubert’s prose poem. At its entrance, he encounters an ancient Indian ascetic philosopher. Although Flaubert gives a haunting description of the man’s starved and weathered nudity, Redon chooses instead to represent the fig tree in which the ascetic lived, with the “natural excavation of the shape of a man” — a striking black form in the lithograph.

Here Redon depicts the Egyptian goddess Isis holding her son Horus, who represents the rising sun. In Flaubert’s text, he is called Harpocrates, the god of silence in Greek mythology. Flaubert describes Isis as holding a long black veil that conceals her figure. In Redon’s imagining of the scene, the veil covers the child and some of Isis’s lower body, draping onto the ground and morphing into blackness that obscures her face.

“Evening Wind” captures a universal sense of mystery. Hopper generalizes much of the image, from the woman’s face obscured by her hair to the simplicity of the interior. The minimal detail allows viewers to picture themselves in this room. The foregrounding of the figure is inviting. The gestural mark making and composition create a sensory experience. One can feel the cold wind and the exposure of the naked figure. What makes this print so unsettling is the anticipation of what comes next. Viewers may feel frightened simply by the possibility of being frightened, pictured by the woman’s gaze at the open windows. Did something catch her attention?

“Jackal” is a lithograph from Bourdelle’s 1945 portfolio, entitled “War.” It is the product of an artist-turned-ambulance driver during the Second World War, which injured and deafened him for the remainder of his life. “Jackal” exists alongside 51 other illustrations that substitute animals for human actors in this theater of “universal bloodshed.” Together, they acknowledge the long precedence of wars that enabled WWII but also the atrocities that distinguished it. In popular folklore, jackals are characterized as tricksters with a keen ability to survive. What horror is experienced by those who survive? Hush for a moment; can you hear it howl?