Richard Prince's "Tell Me Everything" helps viewers examine the role and value of jokes.

Richard Prince's "Tell Me Everything" helps viewers examine the role and value of jokes.

Richard Prince and the Examination of the Value of Jokes

What role do jokes play in your life? Do they impact the way you view the world, or perhaps, help make light of the frustrations in your life? For artist Richard Prince, an examination of jokes illuminates the American subconscious in remarkable ways. In “Tell Me Everything,” his latest exhibition, he challenges viewers to examine the value and meaning of jokes in American culture. On view through June 16 at the Georgia Museum of Art, the works also pay homage to famed comedian Milton Berle, who rose to fame in the late 1940s with an evening TV show and helped propel America’s love of television entertainment to its status today.

“Richard Prince: Tell Me Everything”

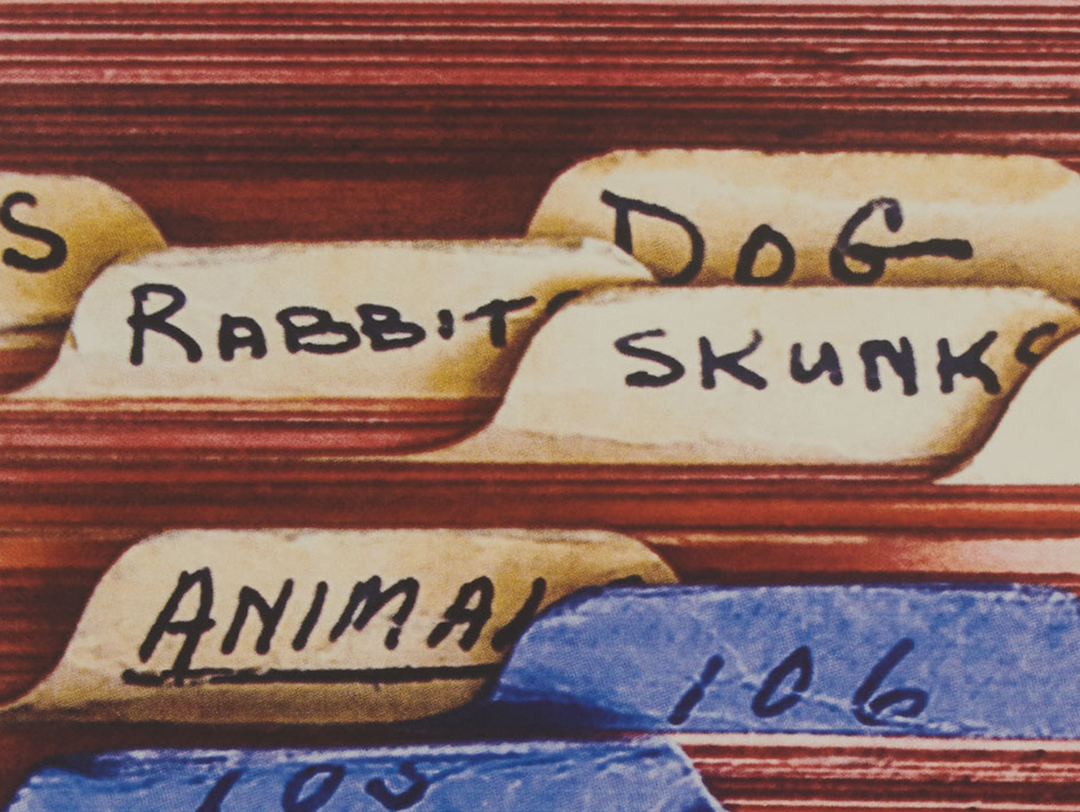

Prince uses the joke files of Berle to help viewers contemplate the subjects that we joke about in modern life. For eight decades, Berle curated a large collection of his jokes, logged on index cards and carefully organized in filing cabinets. At a Los Angeles auction in 2013, Prince bought four of these files and he began making photographs of them, then printing the photos on canvas. His aim was to show the importance of jokes in communicating taboo topics and cultural norms, which he believed expressed the American subconscious.

Comedy and jokes are a natural draw for Prince and his longtime focus on appropriation art. Much like art, a joke is easily repeated, embellished and passed along in a new form for audiences to enjoy. The name of the exhibition, he notes, comes from the first joke that he came across in a secondhand bookshop:

“I went to see a psychiatrist. He said, ‘Tell me everything.’ I did, and now he's doing my act.”

The large-scale works in his exhibition focus on the organization of jokes by subject, as seen in Berle’s filing cabinets. Categories such as divorce, rent, friends, crying and salaries depict themes that are telling about the human experience. He uses these categories to communicate how jokes are a catalyst for ideas. With an aim to create meaning that lasts, he honors the comedic work of Berle while simultaneously creating new messages about life.

Richard Prince and the Advent of Reappropriation Art

This isn’t the first time that Prince’s art has focused on jokes in his career. During his lengthy career as a photographer and painter, he first worked for Time, Inc., then moved on to focusing on his own art. Known for helping pioneer reappropriation art, he is also associated with ruffling feathers. His “rephotographs,” or enlarged versions of photographs, pushed the boundaries of the status quo and he developed a controversial reputation in the art community for reappropriation:

Starting in the mid-1980s, he began making a series of works about jokes. He started with handwritten jokes on pieces of paper, then began silkscreening the text of jokes on painted canvas. Prince sees jokes as expressing the American subconscious and has said, “Being funny is a way to survive.” Despite his critics, his career and challenges to the art community have ultimately paid off.

“The problem with art is, it’s not like the game of golf where you put the ball in the hole. There’s no umpire; there’s no judge. There are no rules,” said Prince. “It’s one of its problems. But it’s also one of the great things about art. It becomes a question of what lasts."

A Common Connection

The connection between Prince and Berle may not be obvious to those unfamiliar with both of their careers, but both are tied to the concept of appropriation. When Berle died at the age of 93 in 2002, the New York Times described him as “the brash comedian who emerged from vaudeville, nightclubs, radio and films to become the first star of television, igniting a national craze for the new medium in the late 1940’s.” His star power, at the onset of television as a new source of entertainment, helped propel the medium forward in a monumental way, noted NYTimes writer Lawrence Van Gelder:

On Tuesday nights at 8 o’clock, families with new black-and-white television sets found themselves welcoming into their living rooms their less privileged neighbors to roar at the antics of Mr. Berle, first on the ''Texaco Star Theater,'' which ran from 1948 to 1954, and then for another year on the ''Buick-Berle Show.'' And before long, those neighbors, too, decided that owning a television set was a sine qua non of early post-World War II life and that to watch Milton Berle walk on the sides of his shoes each week was to laugh in paradise.

Within two months after its debut on Sept. 21, 1948, the ''Texaco Star Theater'' was so popular that it was the only show not canceled to make way for presidential election coverage on the night that Harry S. Truman upset Thomas E. Dewey.

Berle dominated television and became one of the most famous men on television in the 1940s and 1950s.

''Crazy things started happening all over the country,'' Mr. Berle recalled in ''Milton Berle: An Autobiography,'' written with Haskel Frankel (Delacorte, 1974). Nightclubs changed their closing to Tuesday nights from Monday because of the popularity of Mr. Berle's show. Restaurants were empty for the hour he was on the air and business in movie houses and theaters plummeted.

''In Detroit, an investigation took place when the water levels took a drastic drop in the reservoirs on Tuesday nights between 9 and 9:05,'' Mr. Berle wrote. ''It turned out that everyone waited until the end of the 'Texaco Star Theater' before going to the bathroom.''

Like Prince, he was also accused of appropriation and became something that he leaned into and helped, in part, make him a success at the time. Again, the New York Times profile details:

He was famous enough to be subjected to hard knocks. Fellow comics accused him of stealing their jokes, and the powerful gossip columnist Walter Winchell dubbed him ''The Thief of Bad Gags.'' Mr. Berle denied the accusation and resolved to exploit it the way Jack Benny used his reputation for cheapness. So he would joke: ''God, I wish I'd said that, and don't worry, I will,'' and ''I laughed so hard I nearly dropped my pencil and paper.''

Georgia Museum of Art Curatorial Insights

Shawnya Harris, the museum’s deputy director of curatorial and academic affairs and Larry D. and Brenda A. Thompson Curator of African American and African Diasporic Art, knows it may seem like she is an unlikely curator for this exhibition. However, her interest was sparked by her curiosity about Richard Prince and his reputation. Conceptual questions related to originality and ownership drew her in and created a passion for the work that can be seen in the exhibition. The curatorial department hopes to spread this curiosity and reflection to the viewers of “Richard Prince: Tell Me Everything.”

“I have always been curious about Prince’s practice as an artist, which has been both celebrated and critiqued,” she said. “Our curatorial department took an interest in this material as many of us were familiar with Prince’s older joke paintings and his reputation for reappropriation. Although my specialization makes me an unlikely curator to host this exhibition, conceptually I found myself asking lots of questions about value, ownership, originality and how that could engage various audiences using comedy as the basis.”

Related events to the exhibition include the following. We hope you’ll join us in exploring the value of humor and appreciating the work of Prince.

Related events:

-

A performance by Bad ATH Babes comedians on March 14 at 6:30 p.m., with a free reception

-

A Family Day on March 16 from 10 a.m. to noon

-

A creative-aging art workshop geared to ages 55+ with teaching artist Toni Carlucci on April 16 from 10 to 11:30 a.m.

-

An art and wellness studio with art therapist Meg Abbot on May 19 from 2 to 4 p.m.

-

Improv Comedy 101 with Flying Squid Comedy, a class on June 13 from 6 to 8:30 p.m.

-

And the 1963 epic comedy “It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World” on June 13 at 7 p.m.